Bridging Identities

The Cultural Odyssey of

Kurdistani Jews

Scroll down to begin

What is the value of our past? When we carry our languages and stories from one generation to the next, from one country to another, what exactly do we gain?

Ariel Sabar, My Father’s Paradise: A Son's Search For His Family's Past

This exhibition is a journey through the poignant narrative of Kurdistani Jews as they migrated to the land of Israel/Palestine.

Delve into the intricate tapestry of experiences and stories, illuminating the cultural heritage of Kurdish Jews as their resilient journey intertwines historical events and personal aspirations.

There were no seats on the plane. We all sat on the floor. We first came to Haifa where we stayed for five or six months.

When the elderly of our village in Kurdistan saw how green this place (Agur) was, they decided to settle here, 14 families in total. Our houses were made of tin.

--- Yosef

Yosef was born in Qeladizê in Kurdistan. He was raised in Erbil by his aunt after his mother died when he was six months old. He gave his interview in Kurmanji.

My parents spoke Kurmanji and Arabic at home back in Iraq. But when we arrived in Israel, my father said, ‘We’ve come to the country of the Jews, we’ll speak only Hebrew!’

We children spoke Arabic, but once in Israel, he wouldn’t have us speak in any other language. When we learned Hebrew, we spoke with them only in Hebrew.

--- Rachel

Born into a family of Kurdish origin in Baghdad, Rachel immigrated to Israel at the age of five with her family. She may be among the last who still makes her tea in a samovar.

The immigration of Kurdistani Jews to Palestine began as gradual trickles in the 1800s and continued until the mid-twentieth century.

The final mass migration to Israel took place from 1951-52. Around 120,000 Iraqi Jews were airlifted to Israel as part of Operations Ezra and Nehemiah.

According to some estimates, Kurdistani Jews and their descendants number around 150-200,000 in Israel today.

Kurdish Jews, along with other Mizrahi migrants, arrived in Israel without property and in destitute conditions.

Their homecoming was supposed to provide them a life without stigmatisation or discrimination, but these new circumstances in Israel initially failed to meet their expectations.

The images here capture their movements, as families left their homes to begin a new life.

The key is to assimilate into the society that you’re moving into. If you are running from oppression, don't bring the oppression into your new home.

Don't make it follow you … this is a choice that you have made to keep you safe, your family safe for whatever reason.

--- Leah

Leah was born and raised in Israel, then made a significant move to the United Kingdom after her marriage. Establishing herself in the heart of London, she now owns a thriving shop.

Every time I’d go to Israel, I’d be very emotional because I take a lot of Kurdish and Middle Eastern values on family.

But when I talk to my other friends about it, they don't understand it the same way as me.

And I feel like that’s also what drives my consciousness and my passion for being not just a Jew, but a Kurdish Jew.

--- Daniel

Leah's son Daniel recently graduated from university, and together they reside in the vibrant city of London.

I travelled to Kurdistan, the place where our family roots are. I wanted to see where I came from.

Where we visited, people welcomed us so warmly. I even slept in their houses. I failed to observe the Shabbat there. But I think it is fine, it was a once in a lifetime experience after all.

--- Osnat (Asnat)

Osnat was born in Kurdistan and immigrated to Israel as a child in 1951. Today she runs a restaurant from her home in Agur, serving her guests traditional Kurdish dishes and her unparalleled humour on the side.

The Jews of Kurdistan have a rich history which dates back to ancient times...

Nusaybin, Turkey, the home of many Kurdish groups

Nusaybin, Turkey, the home of many Kurdish groups

“The Kal’a”, Erbil. Painting by K. Meir Ben Ozer

In the eighth century BCE, the Assyrians conquered the Northern Kingdom of Israel and forcibly resettled Jews to the region later known as Kurdistan.

Until the mid-twentieth century, Jewish communities, who spoke various dialects of the neo-Aramaic language, existed in all four parts of Kurdistan.

The majority of these communities centred in Iraqi Kurdistan in cities such as Zakho, Amadiya, Aqra, Dohuk, Arbil, Kirkuk and Sulaimaniya.

Inside a typical Jewish home in Erbil. Painting by K. Meir Ben Ozer

They lived in rural areas under the mandate of Kurdish tribes and received protection from Kurdish tribal leaders.

Women washing clothes in the river. Painting by K. Meir Ben Ozer

Women washing clothes in the river. Painting by K. Meir Ben Ozer

“The Kal’a”, Erbil. Painting by K. Meir Ben Ozer

“The Kal’a”, Erbil. Painting by K. Meir Ben Ozer

Inside a typical Jewish home in Erbil. Painting by K. Meir Ben Ozer

Inside a typical Jewish home in Erbil. Painting by K. Meir Ben Ozer

With almost no pictures to remember Kurdistan by, Kurdish Jews often relied on their memory to recreate the Jewish landscape of their once homeland Kurdistan. The above map, which was prepared by the Erbilian Jews’ Heritage Foundation, shows the Jewish neighbourhood of Erbil. Each house is marked by the name of its residents.

With almost no pictures to remember Kurdistan by, Kurdish Jews often relied on their memory to recreate the Jewish landscape of their once homeland Kurdistan. The above map, which was prepared by the Erbilian Jews’ Heritage Foundation, shows the Jewish neighbourhood of Erbil. Each house is marked by the name of its residents.

After centuries of coexistence, outbreaks of violence and discrimination, exemplified by the Farhud pogrom in Baghdad, cast shadows of fear and uncertainty, compelling many to seek refuge in Israel. Faced with perilous circumstances, Kurdish Jews were often forced to leave behind their homes, properties, and cherished belongings, as they embarked on a journey into the unknown.

The Yakutiye Fountain, in the former Jewish neighbourhood of Mardin, Turkey, is called the Jewish Fountain by locals. The exact date of its construction is unknown, but was probably sometime in the 18th or 19th century.

Remarkably, many Kurdish Jews were permitted to leave Iraq under the condition of relinquishing their citizenship and assets, with the solemn pledge of not returning—a bittersweet testament to their unwavering resolve and the sacrifices made in pursuit of a better future.

The Jewish market in Mardin’s Old City.

Their situation grew more precarious with the reorganisation of the Middle East after the First World War and the subsequent emergence of nation-states in the Kurdistan region.

Document of authorisation declaring Rabbi Shalom Shimoni as the shochet (Jewish ritual slaughterer) and the mohel (person who performs ritual Jewish circumcisions) of the city of Zakho in the year 1904-1905.

Document of authorisation declaring Rabbi Shalom Shimoni as the shochet (Jewish ritual slaughterer) and the mohel (person who performs ritual Jewish circumcisions) of the city of Zakho in the year 1904-1905.

Grandmother Zarifa and her three daughters Sara, Osnat and Miriam, c. 1928

Grandmother Zarifa and her three daughters Sara, Osnat and Miriam, c. 1928

The Yakutiye Fountain, in the former Jewish neighbourhood of Mardin, Turkey, is called the Jewish Fountain by locals. The exact date of its construction is unknown, but was probably sometime in the 18th or 19th century.

The Yakutiye Fountain, in the former Jewish neighbourhood of Mardin, Turkey, is called the Jewish Fountain by locals. The exact date of its construction is unknown, but was probably sometime in the 18th or 19th century.

The Jewish market in Mardin’s Old City.

The Jewish market in Mardin’s Old City.

My only surviving aunt passed away two months ago. No one and nothing are left that can connect us to our heritage anymore.

That’s why I wrote a book. That’s why I’m giving this interview so that there is more record. I will die one day too. Soon there will really be no one who is going to preserve these things.

--- Eti

Having hailed from a family from Erbil and grown up within a vibrant Kurdish community in Jerusalem, Eti has always been concerned with immortalising the stories of the Kurdish Jewish community.

In 2019, she published The Mountain Girls, a biographical retelling of the life stories of the women in her family in Kurdistan.

Ever since I was a child, my dream was to be a writer. Even when I first started studying and didn’t know how to read and write well, I knew that I wanted to write a book.

The first book I published was called The Zakho Tales, in which I documented the folk tales that had been passed down orally among generations.

--- Varda

Varda was nine years old when she and her family left Kurdistan in 1951. Because of the hard conditions upon their arrival in Israel, she started working washing clothes.

Her parents didn’t want her to go to school, saying it was shameful for girls to study. She went on to write the first Hebrew- Aramaic-Syriac dictionary in the Zakho dialect.

The first generation of Kurdish Jews who now reside in Israel often reminisce fondly about their days in Kurdistan, despite occasional tensions that may have marked their history.

Having successfully built new lives in Israel, they maintain nostalgic ties to their former homeland.

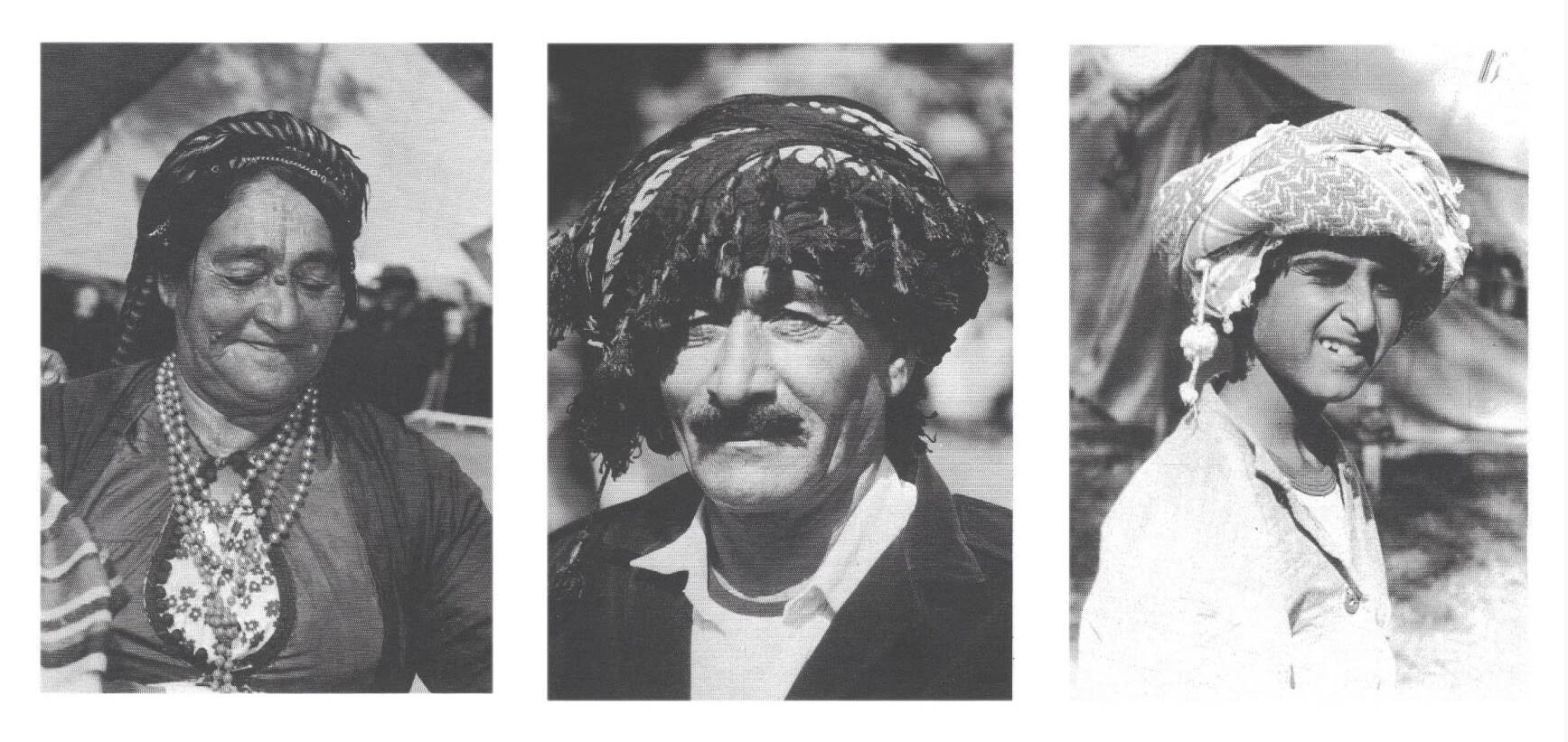

Portraits of people clad in traditional Kurdish clothes during Seharane

Portraits of people clad in traditional Kurdish clothes during Seharane

What is particularly intriguing is their commitment to preserving their heritage through the vibrant mediums of culinary and musical traditions.

By weaving the rich tapestry of their cultural identity into the fabric of their new lives, the Kurdistani Jews not only connect with their roots but also impart a sense of history and belonging to future generations.

The intricate flavours of their traditional cuisine and the evocative melodies of their music serve as powerful conduits for storytelling, encapsulating the essence of their journey – one that embraces both the challenges of the past and the promise of a culturally rich future.

Kurdish musicians playing for Seharane crowds

Kurdish musicians playing for Seharane crowds

A Kurdish woman preparing yaprax (stuffed grape leaves), Jerusalem

A Kurdish woman preparing stuffed grape leaves (yaprax), Jerusalem

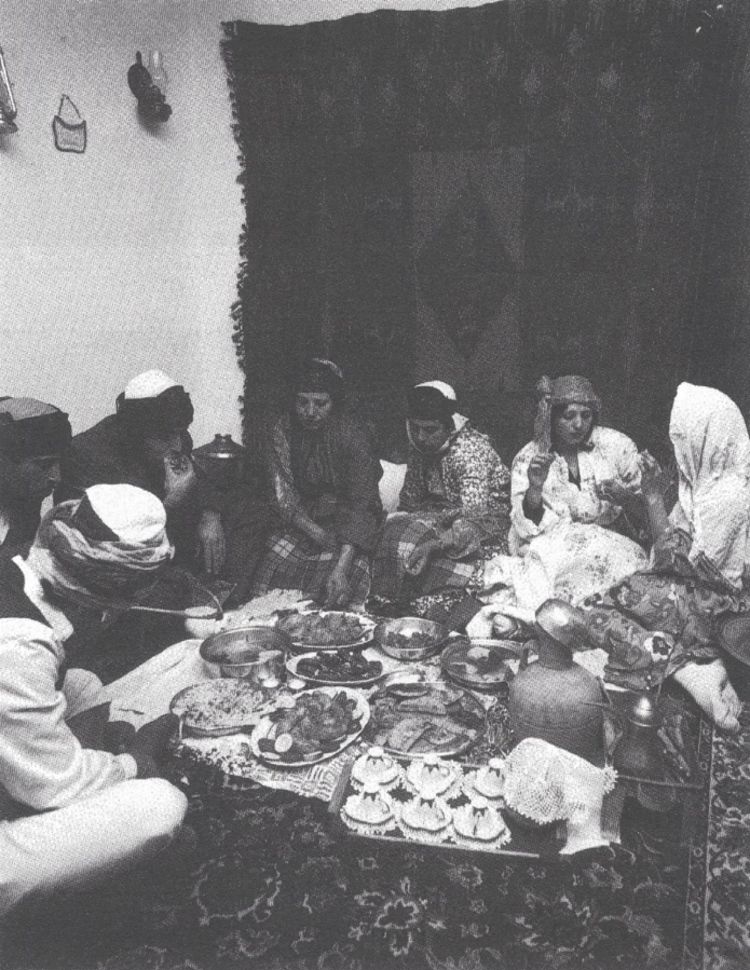

Members of the Kurdish community gathered around a floor table donned with traditional Kurdish dishes for Passover

Members of the Kurdish community gathered around a floor table donned with traditional Kurdish dishes for Passover

Kurdish woman cooking a traditional dish

Kurdish woman cooking a traditional dish

The most visible cultural activity for Kurdish Jews is the Seharane festival, a public celebration accompanied by Kurdish music, dancing, and cuisine, which takes place during the Sukkot holiday in October.

In Kurdistan, the Seharane was originally celebrated during the intermediate days of Pesach (Passover), marking the beginning of spring much like the Kurdish Newroz.

In Israel, the festival was moved to October in 1975 so that the Kurdish festival did not coincide with the Mimouna, the post-Pesach celebration of the much larger Moroccan community.

"I believe that we always have to innovate ourselves. It is the way the modern world works...

…For instance, if you bring clowns or organise the Kurdiyada during the summer holiday when parents can actually bring their children to the festival...

…then the children will have a memory of their own...

…Kurdish culture will be imprinted in their memory...

…When he gets married afterwards, he will want to have the zurna played in his wedding. He will want to dance the Kurdish dances."

--- Liron

Liron is a dance instructor, as well as a dahol player, who holds regular Kurdish dance classes across Israel and performs in ceremonies including weddings.

By teaching Kurdish folk dances and mixing Kurdish music with other influences to increase its appeal and outreach, he seeks to bring Kurdish culture to the forefront in Israel.

Seeing a Kurdish person is such an emotional thing for me.

I feel they are part of me.

I feel like we are the same people.

--- Hadassa

Hadassa is a singer who always performs her songs clad in traditional Kurdish clothes. She sings in Kurdish as well as writing and performing in Nash Didan.

Her dream is to be able to learn both Kurmanji and Sorani, and perhaps one day travel to Kurdistan.

I want to build a Kurdish community museum here (in Jerusalem). Museums are like embassies.

So when someone Kurdish comes to Israel from Kurdistan, Europe or America, they will have a place here.

--- Yehuda

Yehuda is the head of the Kurdish community in Israel. An advocate for closer ties between the two peoples, he frequently appears on television and print media.

What is the value of our past?

When we carry our languages and stories from one generation to the next, from one country to another,

...what exactly do we gain?

This exhibition is the product of field work conducted by Dr. Bahar Baser, Dr. Duygu Atlas, Guliz Vural and Mesut Alp in Israel, May 2023.

The research team interviewed and photographed members of the Kurdistani Jewish community, digitised family photographs and participated in communal activities such as Kurdish dance classes, street performances and traditional cooking.

The objective of this project is to gain insights into how the first generation Kurdistani Jews and their descendants navigate their diverse religious and ethnic identities while establishing a vibrant transnational community within Israel.

The stories in this exhibition shed light on their past through the lens of their memories and nostalgic ties to the homeland they left behind and reveal if and how the markers of Kurdishness are transmitted to generations next.

Watch the video below to go behind the scenes on our research journey!

This project has received funding from the Council for British Research in the Levant (CBRL).

The historic photos and videos featured in this exhibition are courtesy of:

- Osnat Adler

- Eti Feller

- Hithadshut Community Journal of Kurdistani Jews

- Israel Film Archive

- The National Library of Israel: Dan Hadani Collection and Meitar Collection, part of The Pritzker Family National Photography Collection

- The National Library of Israel: Gabi Laron Collection

- Ben Ozer

- Zvi Yehuda

The contemporary portraits were taken by Mesut Alp and Guliz Vural.

The project team is currently collaborating with Moayed Assaf, a Kurdish academic and photographer who has been researching Kurdistani Jewish Heritage in Kurdistan and Israel for his individual projects. He kindly agreed to contribute to this online exhibition with his own portfolio.

This exhibition is the product of field work conducted by Dr. Bahar Baser, Dr. Duygu Atlas, Guliz Vural and Mesut Alp in Israel, May 2023.

The research team interviewed and photographed members of the Kurdistani Jewish community, digitised family photographs and participated in communal activities such as Kurdish dance classes, street performances and traditional cooking.

The objective of this project is to gain insights into how the first generation Kurdistani Jews and their descendants navigate their diverse religious and ethnic identities while establishing a vibrant transnational community within Israel.

The stories in this exhibition shed light on their past through the lens of their memories and nostalgic ties to the homeland they left behind and reveal if and how the markers of Kurdishness are transmitted to generations next.

Watch the video below to go behind the scenes on our research journey!

This project has received funding from the Council for British Research in the Levant (CBRL).

The historic photos and videos featured in this exhibition are courtesy of:

- Osnat Adler

- Eti Feller

- Hithadshut Community Journal of Kurdistani Jews

- Israel Film Archive

- The National Library of Israel: Dan Hadani Collection and Meitar Collection, part of The Pritzker Family National Photography Collection

- The National Library of Israel: Gabi Laron Collection

- Ben Ozer

- Zvi Yehuda

The contemporary portraits were taken by Mesut Alp and Guliz Vural.

The project team is currently collaborating with Moayed Assaf, a Kurdish academic and photographer who has been researching Kurdistani Jewish Heritage in Kurdistan and Israel for his individual projects. He kindly agreed to contribute to this online exhibition with his own portfolio.

Our research with Kurdistani Jewish communities is ongoing.

Click the button below to share your feedback on this exhibition and find details of how to get in touch with the project team.

We'd love to hear your stories.

Explore more of our research with the links below.