The ‘Stay at Home’ regulations have bound us to our homes more than ever in living memory. However, they have also encouraged entirely new ways of experiencing the domestic interior. Dining tables have become work offices or makeshift school desks, kitchens have become bakeries, living rooms have become gyms, and almost every space has provided a studio from which to produce videos and broadcast video calls. These are just some of the new functions that our homes have fulfilled in Lockdown.

What is home?

The home is a deeply personal space. It can mean entirely different things to different people, in terms of scale, relationships and emotions. It can refer to a country, a locality and even a structure. It might be a place you live alone or with others. A place of loving relationships or difficult ones. A place of familiarity, relief and security. Or a place of discomfort, loneliness, confinement and fear. What the home means to each person is inherently individual, but also subject to change. This exhibition reflects on the home as a recurrent theme in art, exploring the vast personal, social and cultural relationships that people have developed with the spaces in which they dwell.

During this pandemic, homes have become a substitute for the gallery space, as a site of (virtual) engagement with art. This exhibition aims to emulate the experience of an exhibition by incorporating a sense of motion within the home, moving From Walls to Windows. As you scroll, we hope that you take a physical or imagined journey through the home – whether it be your current place of residence, a home you remember or one of your imagination. This exhibition’s five sections, based on objects often found in the home – the wall, the table, the chair, the bed and the window – aim to encourage you to reflect on your own home and potentially even encounter this familiar space anew.

Watch the clip below to hear more about the exhibition!

The curators introduce From Walls to Windows. Featuring Charlotte Lock, Yini Wang and Dorry Fox.

Walls

The skeleton of a structure is defined by its walls. From the many feet-thick castles walls, to the layers of brick frequently seen within homes, walls are often associated with protection and security, although they can also be a means of confinement and restriction. Walls of the home can be seen to provide a barrier between the interior and the outside world.

Walls give us something that we claim ownership over. By splitting the space into different segments, walls diversify our physical interaction with it. They provide us the space to live out our private lives, supplying a barrier that separates ‘my space’ from ‘the other space’. This ‘other space’ becomes a mystery. It may tempt us to break the wall, to explore the mystery beyond.

'When I was a little girl, I was fascinated with the book, Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. It collects many short allegorical stories. One of them, as I remember very clearly, is called THE TAOIST PRIEST OF LAO-SHAN. It is a story about 'walking through a wall'. There is an interesting animation of this available online.'

But the wall has its unique meaning in the space. It is not just an implication of distant mystery, but an allusion to the enclosure that conceals our own stories. The wall provides a physical space on which we recount the details of our histories and memories.

The skeleton of the wall can be personalised – a site to express your identity; perhaps being decorated with paint, wallpaper or tiles, like Paula Rego's Little Girl Series 1-8 , or being dressed with objects, from clocks to posters to photographs. The wall can be a space of creative potential, containing our stories and memories.

Paula Rego, Little Girl Series 1-8 (1989). Glazed ceramic tile. Collection of Durham University

Paula Rego, Little Girl Series 1-8 (1989). Glazed ceramic tile. Collection of Durham University

In Sharon Bailey's audio-visual project, Home Alone (2020), we receive a glimpse into Colin's home. The walls are a space of display, to pin important or personal items associated with memories – to show ornaments, icons and cut out pictures. Walls can also be a space in which we are kept alone, away from the rest of the world – a space of loneliness.

An excerpt from Sharon Bailey's project, Home Alone. 'Colin's Walls' was inspired by the artist's diary excerpts, and features photographs of the walls themselves. ©Sharon Bailey 2020

For more information on Sharon Bailey's project Home Alone, follow this link. For more of Sharon's work that deals with the themes of this exhibition, click here.

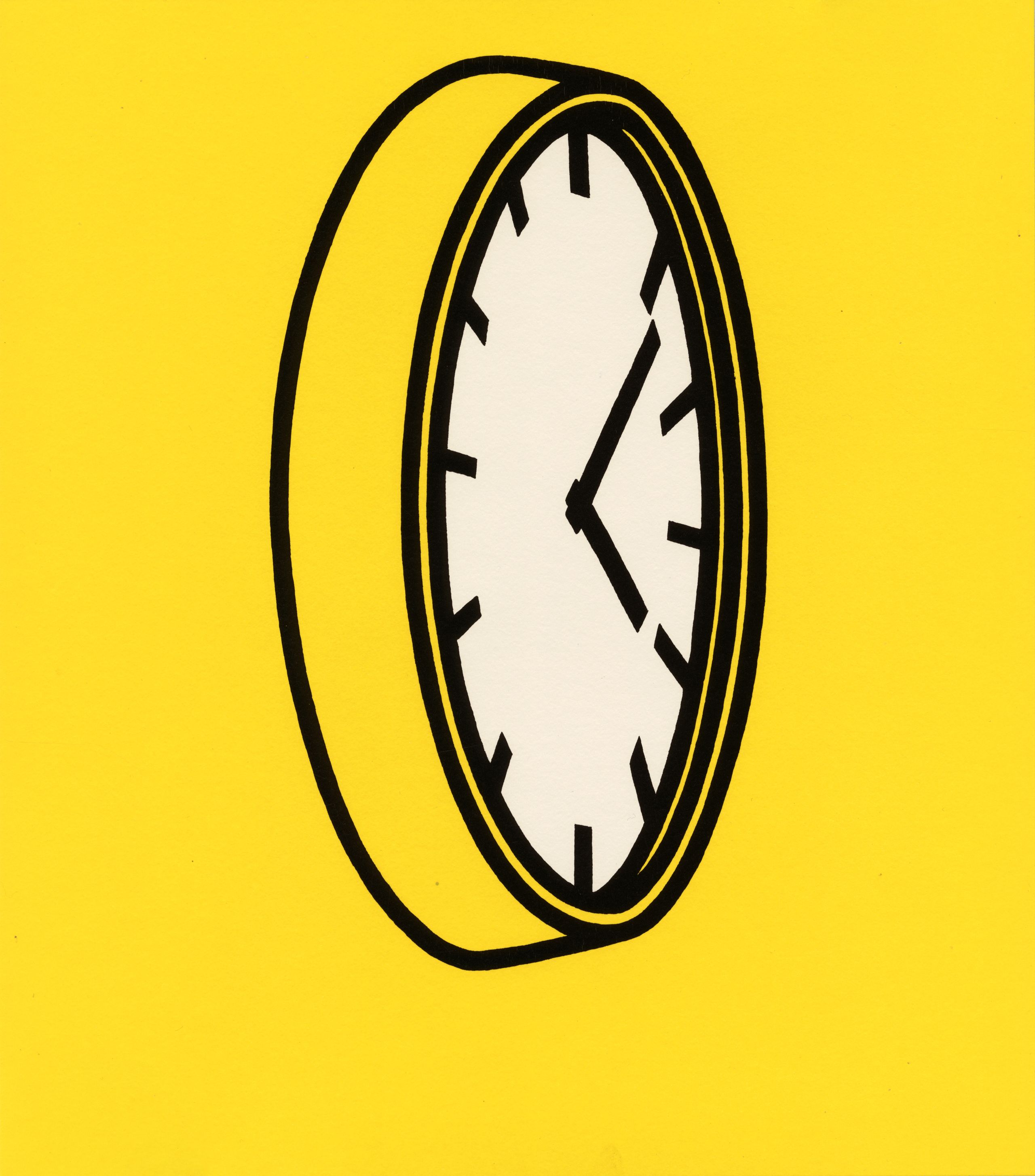

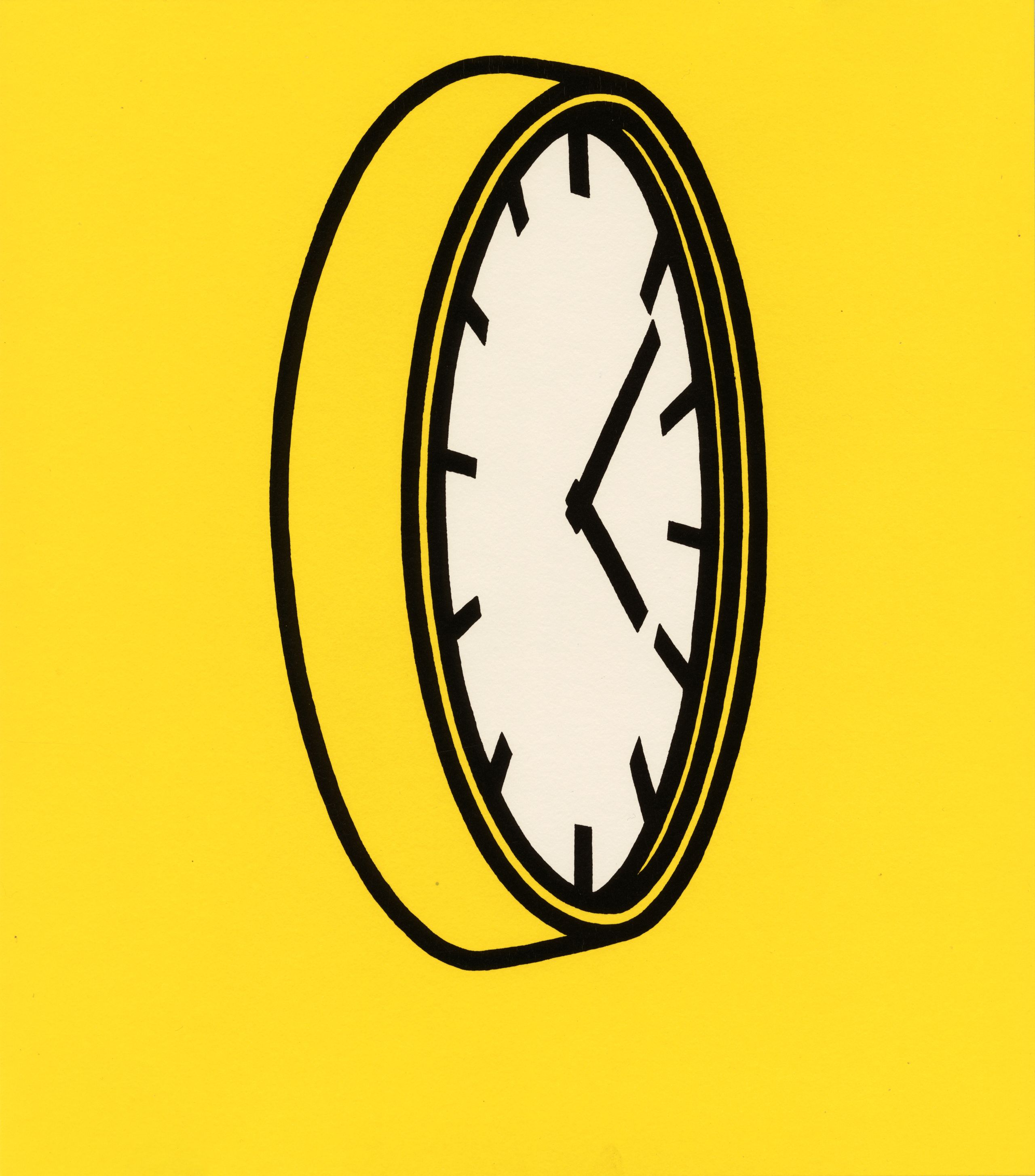

The connection we have with walls is not just spatial, but also temporal. This is the reason why we hang a clock on the wall. It becomes a guide that conducts our daily lives. Perhaps you hardly noticed it. Perhaps you had taken it for granted. Or perhaps you don't hang a clock on your wall, but this does not lessen our association of the clock with this space. The time is reified on the clock panel every time you look at it. It seems to become a necessity not only to us but to the wall.

''You'd better have a clock on the wall,' my mother said to me when I moved into my new apartment. ‘Why must I have a clock on the wall?’, I retorted. ‘Time’, was the answer.'

Perhaps the clock has always kept the wall good company as they embody time and space. Just like the clock renders the time palpable, the wall enables the awareness of the space. The numbers on the clock face resemble the division of space. Different tasks are performed around the home in accordance with time. However, this separation could also allude to something psychological. Patrick Caulfield’s Crying to the Walls seems to recount a deplorable story that leaves us heart-broken. The clock is perceived from a strange angle – we cannot see the clock panel. Caulfield seems to avoid confronting the clock as if he cannot face it straight on. This angle also implies that he leans against the wall as a way to perceive the clock. This connotation is also revealed through the unified bright yellow hue that penetrates both the wall and the clock. Perhaps the clock is a reflection of his own face that he dare not look at. The bright yellow suggests an intention of escape from what is real and actual. The cartoonish form and colour render this setting fictitious. It is detached from reality, and may be consigned to Caulfield’s inner world.

Patrick Caulfield, Crying to the walls: My God! My God! Will she relent? (1973). Screenprint on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Patrick Caulfield, Crying to the walls: My God! My God! Will she relent? (1973). Screenprint on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Patrick Caulfield, Crying to the walls: My God! My God! Will she relent? (1973). Screenprint on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Patrick Caulfield, Crying to the walls: My God! My God! Will she relent? (1973). Screenprint on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Patrick Caulfield, Crying to the walls: My God! My God! Will she relent? (1973). Screenprint on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Patrick Caulfield, Crying to the walls: My God! My God! Will she relent? (1973). Screenprint on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Table

Tables have historically been the centre of many homes, fulfilling a diverse range of functions. Tables are spaces where we place objects. They are also companions in our daily lives. They look so ordinary that we do not even register their existence. Our current circumstances seem to provide us with an opportunity to think about our relationship with the table. What are you using your table for at this moment?

Nowadays, we have more time to arrange our rooms as we do not have to commute from place to place. Time seems to slow down, as if providing us more time to contemplate life. We seem to become closer than ever to domestic objects. They are important components of space – they render the space substantial; their existence enables us to feel the space. We interact with objects not only physically, but also mentally.

We may therefore start to realise that the table is not just a place for piling objects, but a platform from which these objects launch their theatrical performances. We, as the audiences, are not only the off-stage spectators, but also the participants that bring our own emotions to the performances. Yao Yao Li is one who connects herself with the stage.

The following works feature in Yao Yao Li's recent project, The peep series.

Yao Yao Li, Peep Series 1 (2020). Photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

Yao Yao Li, Peep Series 1 (2020). Photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

Yao Yao Li, Peep Series 2 (2020). Photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

Yao Yao Li, Peep Series 2 (2020). Photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

Alison Cookley, Still Life (1973). Acrylic on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Alison Cookley, Still Life (1973). Acrylic on paper. Collection of Durham University.

‘I would sit by the table, just to gaze at the empty plate and cup after having my lunch’, the artist says. ‘It was the first time that I felt so close to these objects. It seemed to me that I could even feel their heartbeats, their emotions that had already fused into mine.... I sit at the table for hours because of that’

There is a connection between her and the table. The table resembles the canvas on which she presents her objects. It is the empty plate that she is gazing at, but at the same time, this emptiness reflects back her own image. She becomes 'the other person' to which she identifies.

The objects we encounter shape who we are and how we understand ourselves.

Artist Yao Yao Li's 'The Peep Series': a collection of works reflecting on her relationship with domestic objects.

For an interview between the curator Yini Wang, and the artist Yao Yao Li, follow this link.

Cookley’s Still Life likewise seems to reveal connection to domestic objects. The harmonious colours and contours of the jar appear to fuse into the background. It is fading into the surrounding space – the table on which it is laid, to which it has been integrated. This may relate to her own relationship with the object; they are connected. The space, a vehicle of our physical being, retains spiritual meaning that correlates to our inner needs. As we sit by the table and physically interact with objects – as we touch the wooden surface, and as our figures glide down its edges – we are aware of our physical being. This harmonious portrait may present Cookley’s inner tranquillity. We see the calmness that she may embrace when she looks at the jar before her. The table is not just a functional object, but becomes a poetic landscape.

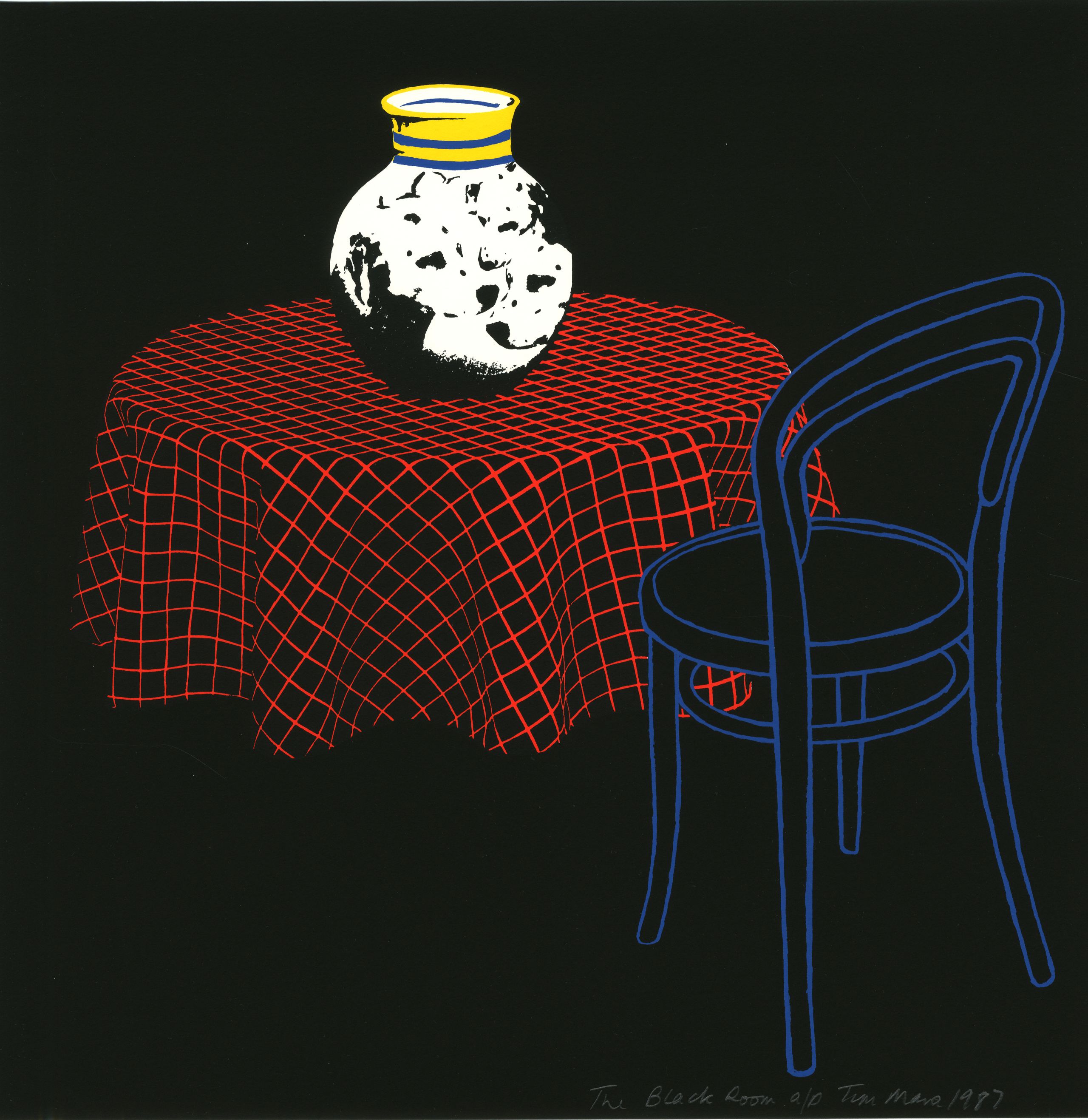

Tim Mara, The Black Room, 1987 Silkscreen on paper, Collection of Durham University. Courtesy of The Tim & Belinda Mara Trust.

Tim Mara, The Black Room, 1987 Silkscreen on paper, Collection of Durham University. Courtesy of The Tim & Belinda Mara Trust.

Tim Mara’s still life endows his objects with unique characters. The vase seems to transform the table into a stage from which it can perform and be observed. The speckled pattern is lively. Contrasting with the black background, it is detached from the original context and states its unique character. Perhaps he is no longer a spectator, but one who is dancing with these objects. This is the connection that domestic objects have with us.

Chair

The noun chair encompasses a diverse range of designs and materials, which adapt to changing tastes and social conditions. This object is a predominantly western phenomenon, and is not ubiquitous across all cultures.

Our instinct to sit comes from the skeleton being structurally unstable, our muscles having to work tirelessly to maintain balance while standing. Despite this, chairs were rare in homes until relatively recently. Those with arms and backs were reserved for individuals of wealth or high status. This symbolic nature of chairs persists today: the individual who runs a meeting is called the ‘chair’, the head of a company may be known as a chairman or woman, and a monarch may be described as ‘on the throne’.

These objects can prove useful in other ways. As demonstrated by Still Life with Chair, their flat surface may behave as substitute tables. Those of us who have difficulty walking or standing may have chairs to aid mobility.

Artist unknown (surname Gildea), Still life with Chair (date unknown). Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Durham University.

Artist unknown (surname Gildea), Still life with Chair (date unknown). Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Durham University.

Since the twentieth century, sedentary work and leisure have developed significantly. Chairs support these behaviours that define modern life in the home—working, eating, conversing, reading, watching television, and, more recently, shopping, messaging, and scrolling on social media. You may be encountering this exhibition from a chair.

We encourage you to observe the following artworks, and to contemplate your relationships with chairs. Think about the chairs in your home: what do you use them for? How much time do you spend sitting in them? What activities do you perform while sitting in a chair? How does the design and feel of the chair affect its role in the home, or your relationship with it?

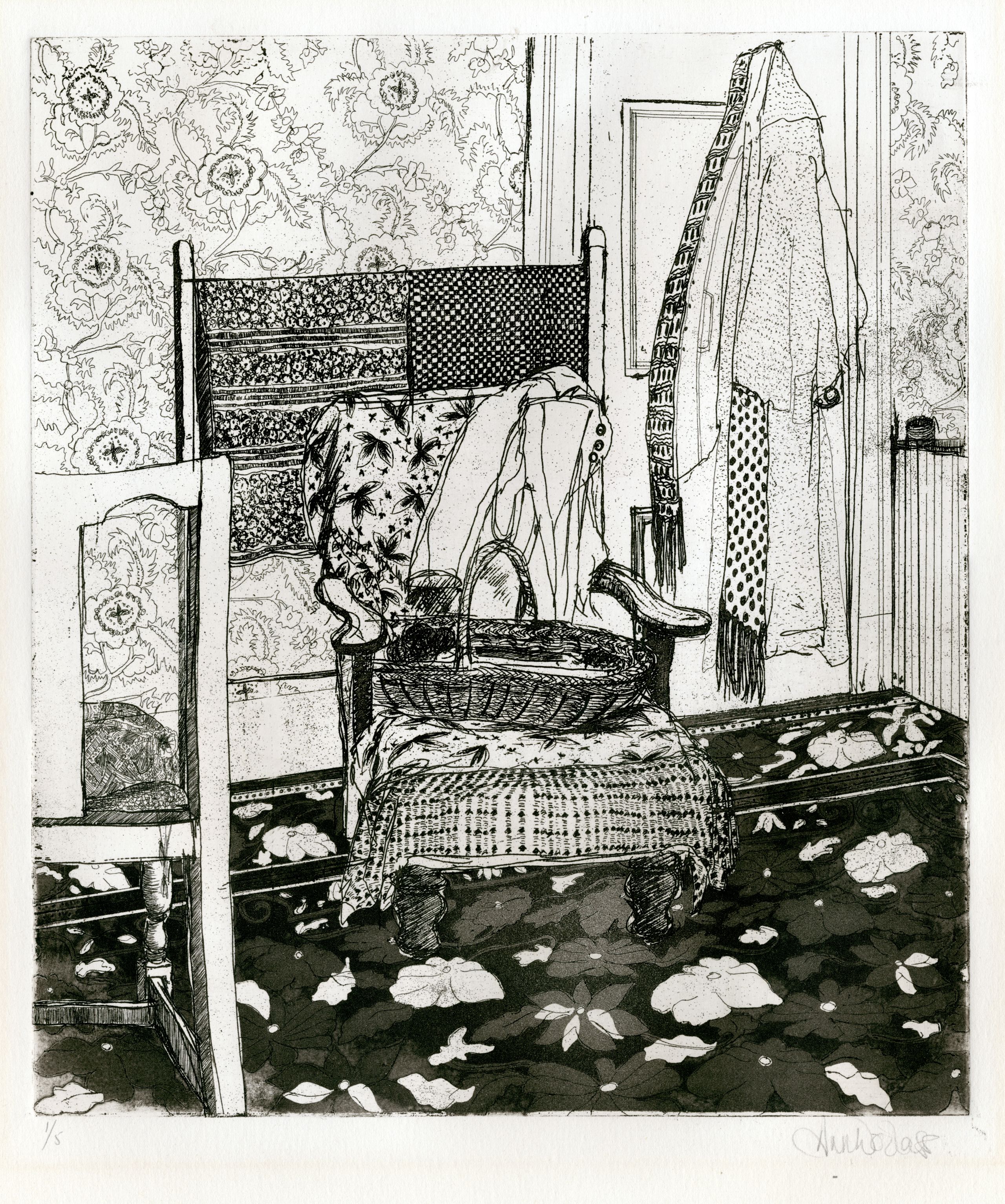

The personality and functions of chairs vary greatly – even amongst those in your home. To sit in the chair on the left of this etching would put us in an upright position. Maybe it is used for productive activities, such as working or grooming. The centre chair, however, seems more informal and untidy –being used as a clothes horse. Its diverse patterns and textures mirror the somewhat chaotic space around it. We could say, therefore, that this chair is more representative of home, comfort and familiarity. We may also wonder whether these chairs act as substitutes for the absent human, as a form of portrait.

‘The chair in my student bedroom was more useful for dumping clothes onto than for sitting. When it was late at night, and I was getting ready for bed, it was too much effort to put clothes back into the wardrobe or chest of drawers. They added new colours and textures, bringing life and vibrancy to the dull upholstery.’

This painting is once again marked by an absent sitter. It was created by Edith Hayllar (1860–1948), one of four sisters who were all successful exhibiting artists in the late nineteenth century. They worked from home, producing genre paintings. Housemaid with Chair is one such scene of everyday life. The missing sitter is presumably the maid’s employer or their family. Her status is signified by her task being to polish – not sit on – the chair. Although domestic staff are not prevalent today, other forms of hierarchy may still be performed in homes. If this is so, chairs may provide one way to demarcate ‘places’ or ‘statuses’ within a household.

The empty chair may have other, more painful connotations. In his project, The House (2018), the photographer Aram Balakjian re-united the memories contained in photographs with the physical spaces from which they were captured. His relationship with the home resembled a form of kinship – it represented the ‘fifth member of [his] family’. Following the deaths of his mother and father – both fellow artists – Balakjian and his sister gradually emptied the house of the objects that brought it life. The empty chair symbolises their experience of bereavement not only for their father, but for their family home, too.

'The inner image was taken just after my dad passed away. The chair was where he always sat while watching TV, so its emptiness signifies his passing. In a way the image has two layers of passing time: the inner image represents the short period between my dad's life and his death. The outer section of the image, meanwhile, shows the change over a longer period – in the clearing of the space, and the implication that the previous period of "loss" will now also be "lost" in a wider sense to the bare physicality of the space in which it existed.'

Finally, we see a chair fulfilling its conventional purpose – to be sat in. The upholstered seat provides a comfortable space to sit for long periods, accommodating different activities in the home. This scene – and its chair – seem to be marked by informality.

‘... a woman sits before a window, the cat at her feet suggesting domestic comfort. Yet she is posed awkwardly in the easy chair in front of a window that is more sky than glass; the space floats above us in an almost dreamlike state. Sarah epitomises the postmodern disruption of domestic norms. Her posture requires an engagement with the viewer that lacks the passive and conflated quality of the traditional domestic portrait where body, clothing, and space are one. Harmony is suggested through horizontal bands of bluish-green sky, while the earthy tones of her slightly skewed vertical figure are harsh against the flat, stark paleness of her skin. She does not meld with her background; the woman is fully aware of her presence. Is she the art, is the interior the art, or is the comfort of domesticity all a figment of our imagination?’

Perhaps the awareness of presence to which Dr Cesare refers suggests that Sarah’s relationship with the chair is momentary. They are not bound together, but rather, she may be ready to stand up and regain her human independence from the object. If possible, perhaps use this time to move from where you are, or to change your perspective. Remember that, although our identities are shaped by the objects around us, they do not define who we are.

Anne Woolass, Interior (twentieth century). Etching on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Anne Woolass, Interior (twentieth century). Etching on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Edith Hayllar, Housemaid Polishing a Chair (date unknown). Oil on canvas. Private collection. Photographed by Leeds Museums and Galleries.

Edith Hayllar, Housemaid Polishing a Chair (date unknown). Oil on canvas. Private collection. Photographed by Leeds Museums and Galleries.

Aram Balakjian, 'Living Room 2017', The House (2018). Photograph. Private collection. Courtesy of the artist.

Aram Balakjian, 'Living Room 2017', The House (2018). Photograph. Private collection. Courtesy of the artist.

Artist unknown (surname Barnes), Sarah (late twentieth century). Silkscreen on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Artist unknown (surname Barnes), Sarah (late twentieth century). Silkscreen on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Bed

Humans spend approximately one third of their lives sleeping. Besides that, many of us were conceived and born in beds, and many of us may die in a bed. We must never underestimate the centrality of these objects to our existence.

One of the primal functions of shelters – for all species – is to provide a safe space for altered consciousness. This is a time when we are at our most vulnerable to danger. The bed is a space where we lay ourselves – our bodies, identities, and insecurities – bare and exposed: a state exemplified by Kraig Wilson’s Joanne (see below).

In the past, multiple family members would often sleep in the same bed. As dwellings became larger and beds more affordable, we came to associate bed-sharing with romantic and intimate relationships.

Many of us have our own beds – private spaces of relaxation and familiarity. This emotional bond is a deep-rooted and personal one. The bed is a place where our formative experiences took place: perhaps the first point of contact to this world, and perhaps a place of parent-child bonding – of cuddling, bedtime stories and kisses goodnight.

However, this place may be wracked with difficulties. When we are affected by physical and mental health problems, we are often confined to the bed. It is also the space where we confront our deepest sub-conscious – our dreams, anxieties and nightmares.

Being a place where we are almost fully exposed, the person with whom we share a bed may make us feel vulnerable and insecure. It might be a space where a difficult relationship with someone is concentrated or augmented.

The diverse connotations of these objects are embedded in their depictions in visual culture. While studying these pictures, consider what bed means to you.

Gustav Klimt, Zwei Liegende (Two Reclining Figures) (c.1916). Lithograph on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Gustav Klimt, Zwei Liegende (Two Reclining Figures) (c.1916). Lithograph on paper. Collection of Durham University.

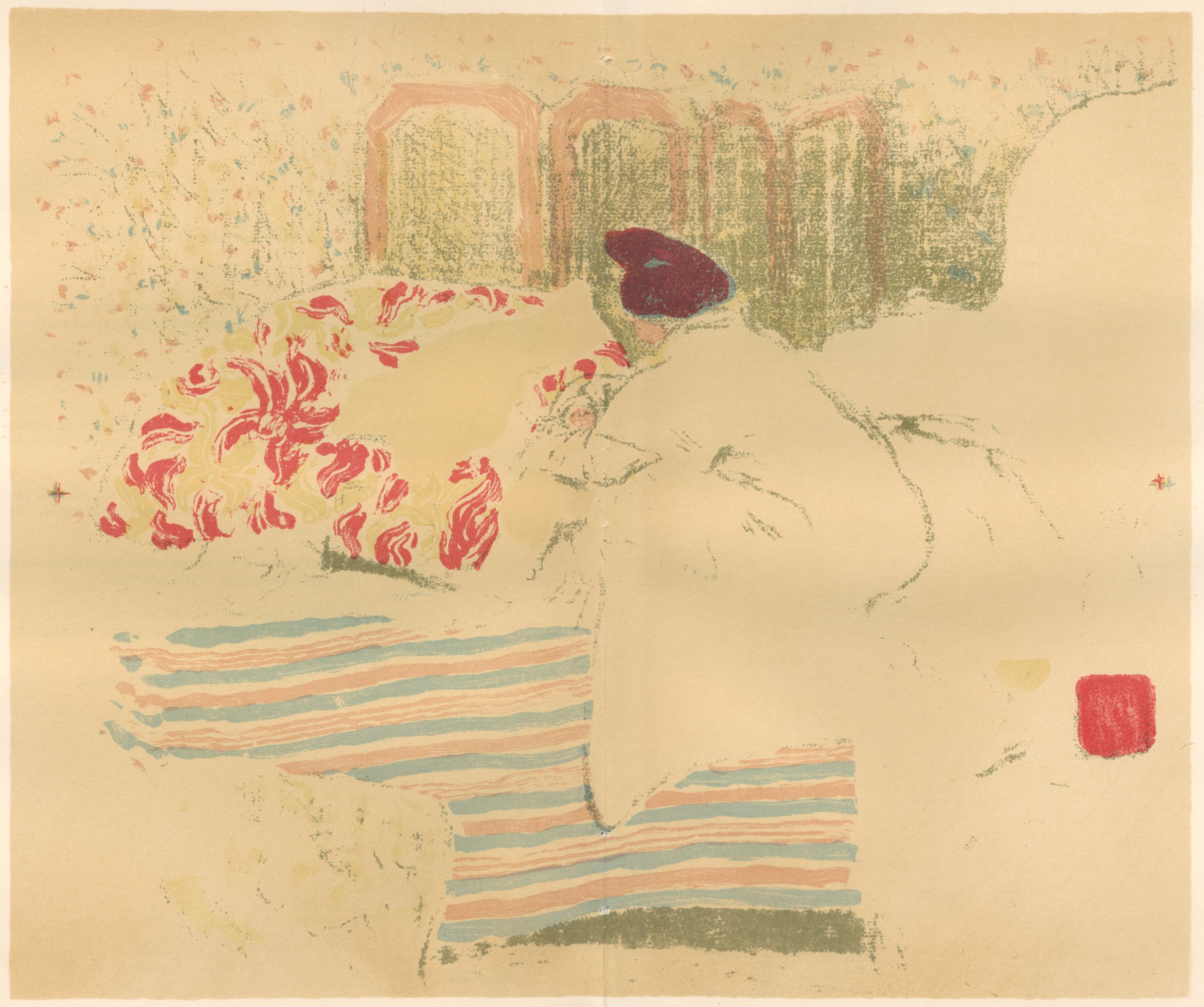

Édouard Vuillard, The Birth of Annette (1899). Lithograph on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Édouard Vuillard, The Birth of Annette (1899). Lithograph on paper. Collection of Durham University.

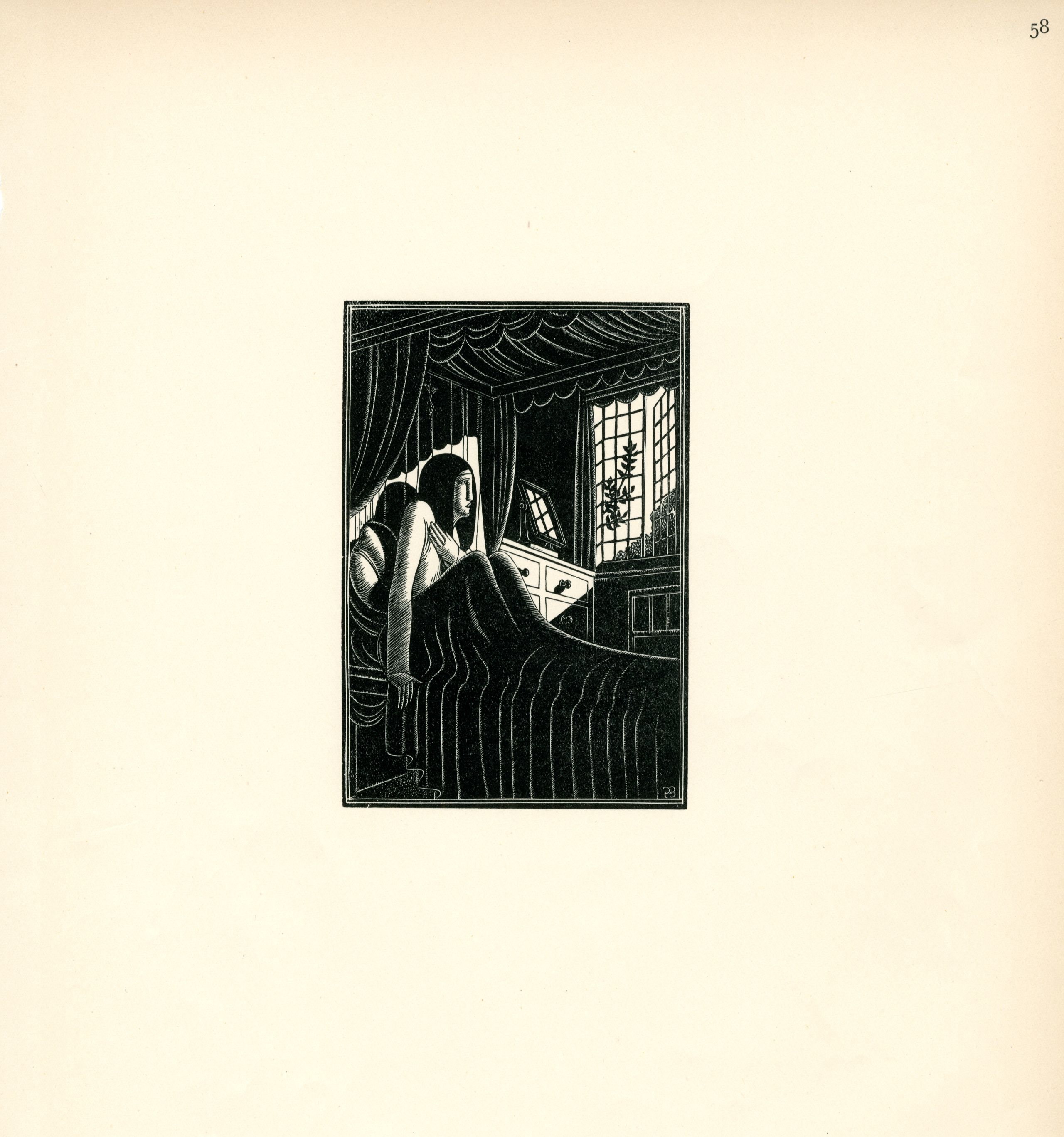

Eric Gill, Autumn Midnight (1929). Wood engraving. Collection of Durham University.

Eric Gill, Autumn Midnight (1929). Wood engraving. Collection of Durham University.

Kraig Wilson, Joanne (2009). C-print photograph on Hahnemuhle paper. Collection of Durham University. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph by Mark Parham.

Kraig Wilson, Joanne (2009). C-print photograph on Hahnemuhle paper. Collection of Durham University. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph by Mark Parham.

Gustav Klimt may be best known for his opulent and fleshy paintings of the female body – works which reputedly epitomise ‘fin-de-siècle’ Vienna. He also produced many erotic drawings, some of which were never seen or exhibited until after his death. This lithograph is perhaps less salacious than its contemporaries, but there is something sensual about these sleeping figures. We cannot discern many physical features of the bed, yet we know it is there. Rendered in single black lines, and avoiding allusion to shade or colour, the bed is united with its occupants in a kind of human-object relationship. They are fused together in the quiet pleasure of sleep. This mirrors the common association of the bed with romantic love and intimacy.

‘Owing to the strong, personal attachment I have for my bed, I often find it a struggle to sleep elsewhere. It is the classic Goldilocks principle: the spring of the mattress, the thickness of the pillows and the texture of the sheets have to be ‘just right’ in order for me to sleep well.’

The Birth of Annette presents a curiously minimalist yet decorative interior, containing a bed that is signalled by just a few lines and a mass of striped colours. This representation perhaps relates to the personal and cultural context of the piece. During the 1890s, Édouard Vuillard was a member of Les Nabis: a Paris-based group who strove to shake off technical precision to focus on the expressive power of colour, pattern and distortion. The figures seem to dissolve into the sheets, their presence indicated by mere flecks of pink and brown. They are at one with each other and with the bed, perhaps suggesting that – just like mother-child relationships – the close bond we form with our bed starts at birth.

Nevertheless, this relationship may not always be a kind and nurturing one.

'This wood engraving by Eric Gill (1882-1940), entitled entitled 'Autumn Winter', was featured in a book of poems of the same name by Frances Darwin Cornford. Both reflect upon the turning of the seasons, as winter encroaches. Through use of chiaroscuro and liminal imagery, with only a shard of light illuminating the subject’s face through the window, the print might imply that home and bed are places of warmth and refuge at a time of ensuing darkness, until spring comes again.

However, home is not always this assured and safe haven for everyone. Knowledge that Gill sexually abused two of his children may complicate this reading.'

An awareness of Eric Gill's background might alter our understanding of this picture. We may decide that its depiction of the bed does not look soft, warm, comfortable and affectionate. The striking monochrome may have been determined by the economy and suitability of black ink for mass printing. Alternatively, however, we could say that it delivers a dark, haunting mood to this piece. The bed may look harder, colder and more stone-like. Something may have stirred the sleepless figure, who clenches at their chest and looks out through the illuminated window. Perhaps they appear to have woken from a nightmare, and turn to the window for assurance of reality. Or perhaps they gaze to the outside world, contemplating that which lies beyond the confines of their room.

My room’s a square and candle-lighted boat,

In the surrounding depths of night afloat.

My windows are the portholes, and the seas

The sound of rain on the dark apple-trees.

Can we separate the art from the troublesome context under which it was made? You can discover more about this issue, and how it relates to Gill's work, in Fisun Güner's article from BBC Culture. This essay contains adult themes that some readers may find distressing.

Kraig Wilson's Joanne seems to provide a very intimate and private view of its subject. It appears that we, the viewer, have infiltrated her personal space on the bed.

'Home isn't safe for everyone. Isolated and lonely, Joanne brings an intimate stillness that is far removed from viewing the bedroom as a place of ‘rest’, but instead captures an ‘intrusion’. As a viewer, my encounter was steeped in perceiving a dark reality experienced by many. During lockdown there has been a reduced need for perpetrators of abuse to hide behind a socially charming mask. Isolated and powerless behind closed doors, there are increasing numbers of men, women and children experiencing and witnessing domestic abuse during lockdown. A recent Women’s Aide survey reported that two-thirds of survivors say their abuse is escalating during lockdown, with 72% saying their abuser had more control over their life since lockdown. #NotAllSafeAtHome.'

We could say that a key element to this piece is its title. The figure has an identity, a name – Joanne. She is not invisible. She is not forgotten. Whatever happens behind closed doors, we are not alone. There are always people who will provide help and support. (You can find helplines at the end of this exhibition).

Window

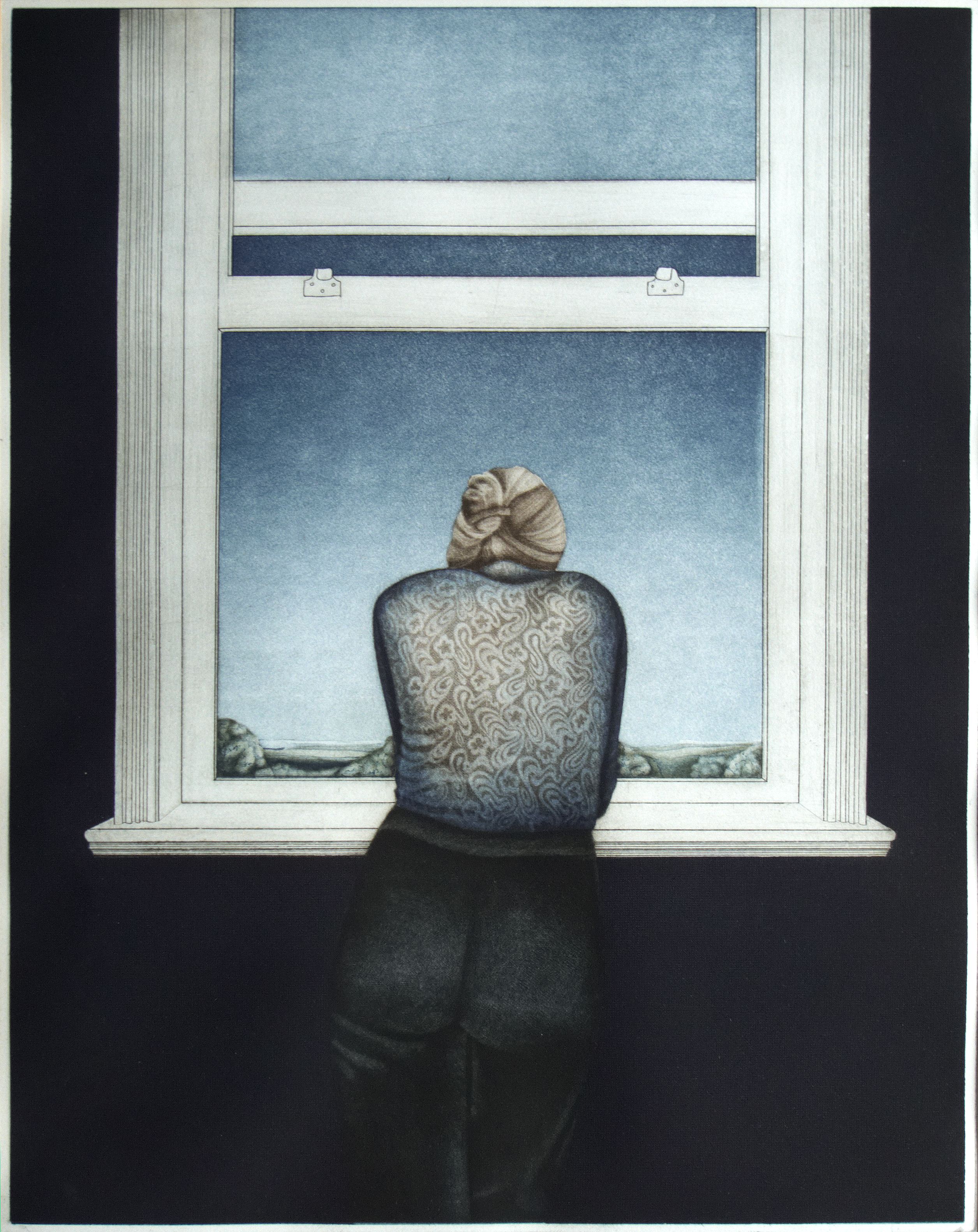

Windows are a central part of almost any building. Historically, windows were open holes in a wall. Today, glass is frequently used, working doubly as an aperture through which the external world can be seen, and light can enter a space. The transparency of windows provides an opportunity for vision, looking from the space of the home onto what lies beyond this structure – from street, to garden, to city, to country, to another home. Eleanor Rigby and Girl at the Window portray how windows can encourage such viewing and reflection, a place for one to dwell and look beyond the space of the home.

Artist unknown, Girl at the Window (date unknown). Aquatint on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Artist unknown, Girl at the Window (date unknown). Aquatint on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Acting as a connection between the internal space of the home and the external world, windows can break down the distinction between interior and exterior. Windows might establish connection to a garden or to a neighbourhood, they have even recently been used to display images of rainbows – symbols of hope – communicating with others when connection is otherwise limited. What do your windows connect you to?

‘I’ve been told that when I was younger I would wait at the window for when the refuse truck would arrive, watching the house perpendicular to me, for when my friend’s head would pop up, at which point, we would wave avidly at each other from our windows.’

The window can even be a place of imagination and inspiration, as in Wight and Barney’s works. It can provide connection to new things, and a place from which to look out onto the world beyond the home. Often, the window is even used as a metaphor for insight and understanding; it can be an object onto which we can project our dreams and desires and receive insight into future possibilities.

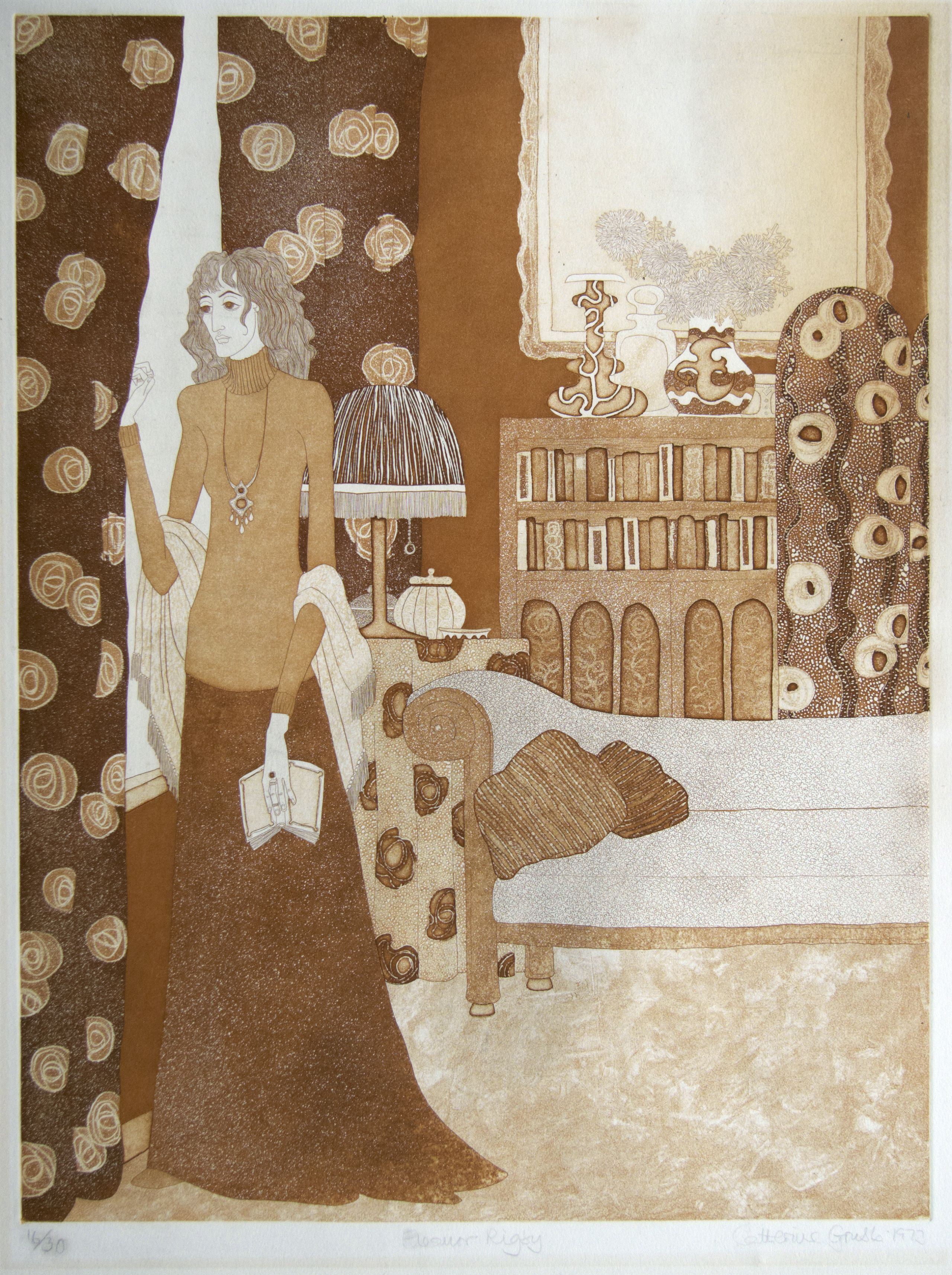

Catherine Grubb’s Eleanor Rigby is a representation of the titular character from The Beatles’ song, Eleanor Rigby, which explores loneliness and isolation; sentiments which can be associated with the home. The song lyrics say she ‘Waits at the window’, as the woman does here; parting the curtains as she looks outside, her attention captured by something unseen. The window, despite not being visible, becomes a place of looking, of waiting, associated with time. Grubb might be seen to explore the relationship between a person and their home – how, regardless of the interior space, we might still feel wanting, looking beyond.

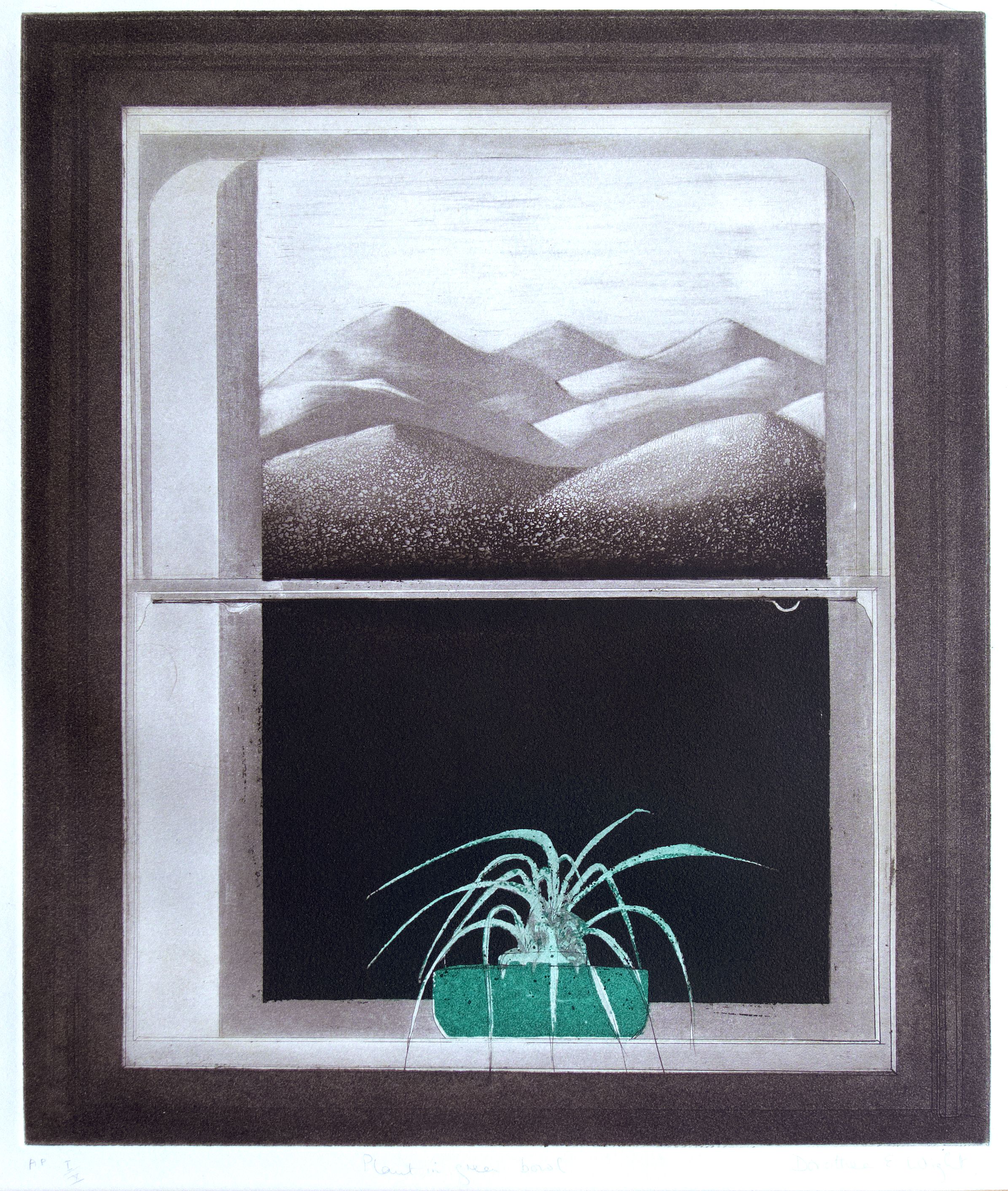

Dorothea Wight’s Plant in Green Bowl further depicts the window as a point of interest – something which offers connection to what lies beyond the home. Through the sash window, this largely monochrome mezzotint reveals contrasting views – an opaque black space, and perhaps a mountainous landscape. Through this split portrayal, Wight arguably aligns the window with imagination and possibility; the view from our window can be more than the reality of what is there. We are even reminded of the links between windows and light through the flourishing burst of green in the potted plant on the windowsill.

Wight's son, Aram Balakjian, reflects on his mother's practice: 'Dorothea's work explores the relationship between the "outside" and the "inside", and how the interplay of these most fundamental physical characteristics offer us a view into the human condition itself. Often inspired by the Devonshire hills of her childhood, Dorothea's use of mezzotint allows her work to contrast the softness of the exterior landscapes with the hardness of interior manmade structures.'

Aram Balakjian's 'Mum's Studio, 2008' is another work from The House series. He overlays a photograph of his mother, Dorothea Wight, working in her home studio, with the room now emptied of the objects that enabled her creative practice. Balakjian writes, 'The House was not only a space for family life, but also for my parents’ work as artists and printmakers.' We can see the home as a space of creativity – that can both inspire and provide a place of making.

The home is also a creative space for artists such as Katherine Barney, whose windows provide a source of inspiration for her ceramics. These works draw on the flora and fauna from her garden. In Blue Poppies on White Athena Jug, the vivid, deep blue hues mirror the flowers behind. Poppies stretch up the jug, accompanied by their leafy stems, as though reaching for sunlight. Drawing links between her work and her home, Barney brings some of this exterior world inside the home, as she reflects her garden in her painted ceramics.

Watch the video below to find out more about how the artist's work relates to her home.

The artist Katherine Barney reflects on the influence of 'the window' on her work.

Catherine Grubb, Eleanor Rigby (1973). Silkscreen on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Catherine Grubb, Eleanor Rigby (1973). Silkscreen on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Dorothea Wight, Plant in Green Bowl (date unknown). Mezzotint on paper. Collection of Durham University, Courtesy of the artist's estate.

Dorothea Wight, Plant in Green Bowl (date unknown). Mezzotint on paper. Collection of Durham University, Courtesy of the artist's estate.

Aram Balakjian, 'Mum's Studio, 2008', The House (2018). Photograph. Private collection. Courtesy of the artist.

Aram Balakjian, 'Mum's Studio, 2008', The House (2018). Photograph. Private collection. Courtesy of the artist.

Katherine Barney, Blue Poppies on White Athena Jug (date unknown). Glazed ceramic jug. Courtesy of the artist.

Katherine Barney, Blue Poppies on White Athena Jug (date unknown). Glazed ceramic jug. Courtesy of the artist.

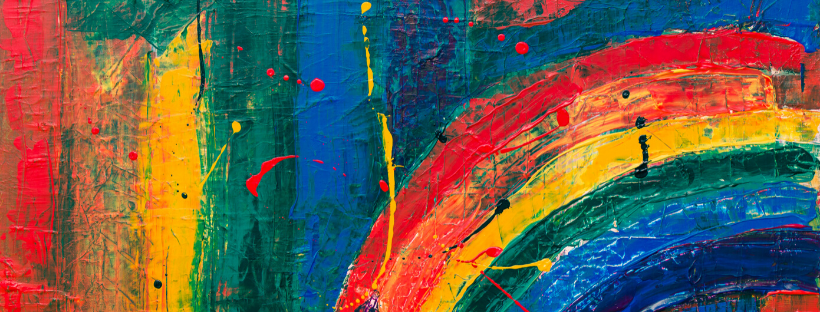

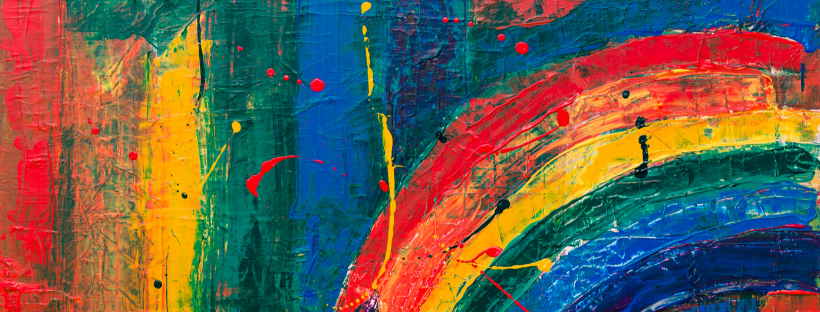

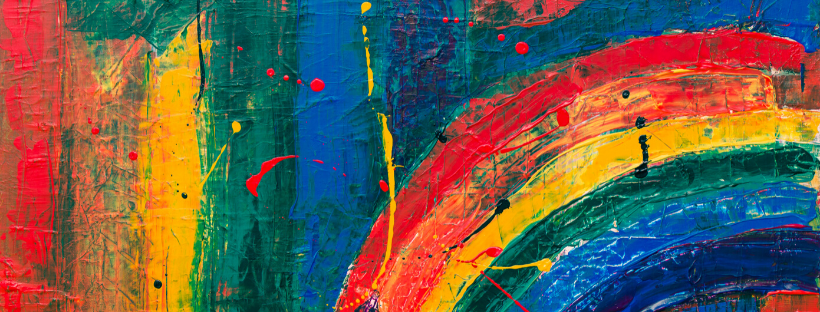

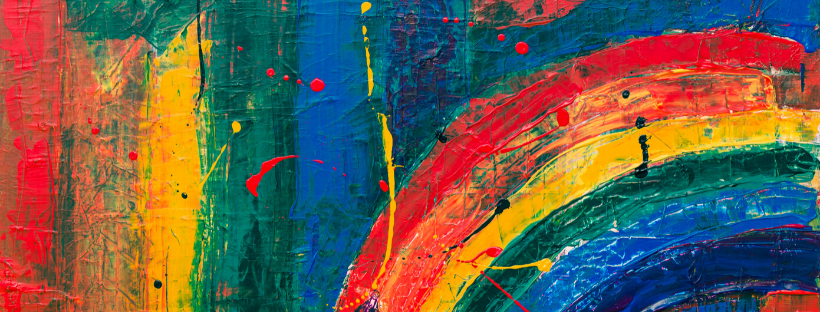

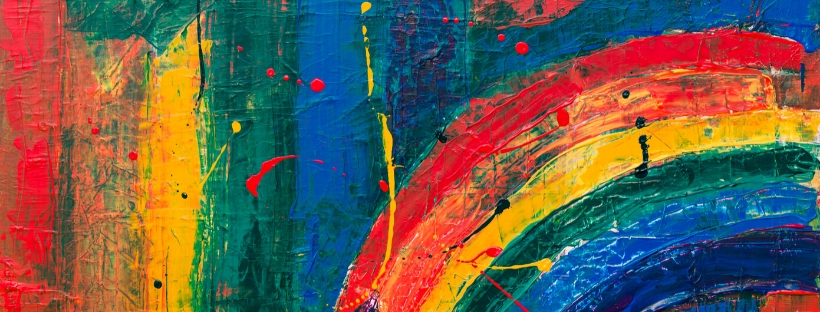

The divide between interior and exterior typically associated with structures is further interrupted in Gillian Ayres' Crivelli’s Room. This print re-creates one corner of a well-known religious work in The National Gallery, The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius (1486), by Carlo Crivelli. Ayres re-imagines this work through abstraction and the use of vibrant block colours. Focusing on this element of Crivelli’s work, Ayres emphasises the open transition and a sense of connection between the home and the outside world.

Gillian Ayres, Crivelli’s Room I (1967). Screenprint on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Gillian Ayres, Crivelli’s Room I (1967). Screenprint on paper. Collection of Durham University.

Dr Paul Harrison reflects on the meaning of home

There’s my place in the sun: behold the image and beginning of the entire earth’s usurpation.

What is a home (okios)? It is always a question of selection, of partition, of economy (oikonomia). A principle of selection. A door and a wall, perhaps a window, this is all that is needed to set the play in motion, the play of inside and outside, here and there, private and public, home and elsewhere. It is the threshold and the hinge which define the home. Like the eyelids or the hand, like a border or a book, or like a hedgehog or a snail in its shell, it can be open or closed, curled-in on itself or open to the elements. The question is always how to work this hinge, how to select, who or what shall be acknowledged, admitted, who or what is worthy of hospitality and who or what shall be turned away, unrecognised. There is no history or geography of the home without a history and geography of hospitality, of its cultures and its modes, its gratuity and its conditioning, its laws and their suspension, its risks and its chances. Its withdrawal and its placing in abeyance. Everything, including history and geography and what shall be admitted to them and in them, begins at this threshold.

Because there is selection a certain injustice always begins here as well. As something given, hospitality can be withdrawn. But who gives? The master of the house (kyrios), the one who assumes or appropriates the role of host, that is, the one who polices the hinge and oversees the economy - be that economy monetary, sexual, symbolic, emotional, or otherwise - can choose to make the environment hostile. Let us be clear, this is always a choice, even when those who made it remain unaccountable. No, despite what Heidegger* tells us, the answer to the question of the home and of how to dwell has not gone astray or been forgotten, it has not been lost somewhere on the way to tomorrow, because the question of the home is always a question of and for the future. It is first and foremost an ethical question. Urgent and insistent, it is the question of how to live together. Of what we welcome and what we close our eyes to, if we curl our hand into a fist or open it in greeting. No, it is not a question which has ever had an answer but, on a good day, it is an invitation to experiment, to test the play of the hinge. And we will not know what is possible until, as Audre Lorde said, we start to dismantle the master’s house. What is the home? It is always a question for and of the future because we still do not know what a home could be. The chance of a greater hospitality, which is the chance of the future itself.

– By Dr Paul Harrison, Associate Professor in the Department of Geography at Durham University

*Heidegger’s philosophical thought on dwelling has been influential in scholarship on the home. However, there is debate over the use of his work due to its deeply problematic context, and as such it has been engaged with critically and cautiously here. Further information about this can be seen in Rothman’s article.

Changing Relations – Words from Pollyanna Turner, Artistic Director, Changing Relations C.I.C

Like COVID-19, domestic abuse does not discriminate. Anyone can be affected regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, religion, sexuality or income. In the year ending March 2019, an estimated 1.6 million women and 786,000 men experienced domestic abuse - that's almost 1 in 3 women age 16 - 59 and close to 1 in 8 men experiencing abuse in their lifetime. For them, social distancing is not a choice and there is no end to lockdown. At home, every aspect of their daily lives is being controlled by their abuser and lockdown has only further removed them from vital links with friends, family and colleagues who could potentially offer help and support.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, arts organisation Changing Relations are raising awareness of domestic abuse and the breadth of its manifestations and people who could be affected during the enforced lockdown. They have been using the hashtag #NotAllSafeAtHome to highlight organisations which offer help to victims of abuse and sharing excerpts of victim-survivor stories from ‘Us too’ - a moving and powerful soundscape produced by Changing Relations which gives voice to the unheard victims of domestic abuse - with a hope to raise awareness of domestic abuse and to help people be better able to recognise the breadth and diversity of people who could be affected by - and indeed - perpetrate - domestic abuse.

You can find them on Instagram (@ChangingRelations), Facebook and Twitter (@ChangeRelations)

Many thanks to

Faryal Arif & Nadin Hassan

Sharon Bailey

Aram Balakjian

Katherine Barney

Dr Carla Cesare

Changing Relations

Alix Collingwood-Swinburn

Dr Hazel Donkin

Helena Grimmer

Dr Paul Harrison

Yao Yao Li

The Summer in the City team

Pollyanna Turner

Find us on Social Media

To find out more about this project, the curators, and family-friendly activities, follow our social media accounts:

Instagram: @walls_to_windows

Twitter: @FromWalls

Your feedback is really important to us. Please help us by completing this short questionnaire. Thank you.

Further Resources

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this exhibition, the following organisations may be able to provide support and advice:

The Freephone, 24-hour National Domestic Abuse helpline, offers information and specialist support and advice: 0808 2000 247

Women’s Aid and Refuge have websites with comprehensive advice for those who are – or suspect someone you know is – experiencing domestic abuse.

If you have been physically hurt, or feel like you are in immediate danger, you can call the Police: 999.

Childline has a 24 hour confidential listening service for children: 0800 1111

NSPCC provide advice for adults who are worried about a child: 0808 800 5000 (24 hours)

Respect run Men’s Advice Line for men experiencing domestic abuse: 0808 801 0327

Specialist support service Galop offer emotional and practical support to LGBT+ victims and survivors: 0800 999 5428

The Age UK Advice Line offers support targeted at those who are older: 0800 678 1602

Your Local Authority should be able to provide local information about safe houses, refuges, outreach services and specialist support for domestic abuse victim-survivors.

Cruse Bereavement Care offers emotional support to anyone affected by bereavement. Day by Day Helpline: 0808 808 1677

Samaritans offers free emotional support 24 hours a day: 116 123

The Silver Line offers a free helpline 24 hours a day for older people: 0800 4 70 80 90

With thanks to Changing Relations for their support and assistance.

List of Artworks

Gillian Ayres, Crivelli’s Room I (1967). Screenprint on paper. Collection of Durham University. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Sharon Bailey, 'Colin's Walls', from Home Alone (2020). Video. Courtesy of the artist.

Aram Balakjian, 'Living Room 2017', from The House (2018). Photograph. Private collection. Courtesy of the artist.

Aram Balakjian, 'Mum's Studio, 2008', from The House (2018). Photograph. Private collection. Courtesy of the artist.

Artist unknown (surname Barnes), Sarah (late twentieth century). Silkscreen on paper. Collection of Durham University. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Katherine Barney, Blue Poppies on White Athena Jug. (date unknown), Glazed ceramic jug. Courtesy of the artist.

Patrick Caulfield, Crying to the walls: My God! My God! Will she relent? (1973). Screenprint on paper. Collection of Durham University. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Alison Cookley, Still Life (1973). Acrylic on paper. Collection of Durham University. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Artist unknown (surname Gildea), Still life with Chair (date unknown). Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Durham University. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Eric Gill, Autumn Midnight (1929). Wood engraving. Collection of Durham University. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Catherine Grubb, Eleanor Rigby (1973). Silkscreen on paper. Collection of Durham University. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Edith Hayllar, Housemaid Polishing a Chair (date unknown). Oil on canvas. Private collection. Photograph by Leeds Museums and Galleries.

Gustav Klimt, Zwei Liegende (Two Reclining Figures) (c.1916). Lithograph on paper. Collection of Durham University. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Yao Yao Li, Peep Series 1 (2020). Photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

Yao Yao Li, Peep Series 2 (2020). Photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

Yao Yao Li, The Peep Series (2020). Video. Courtesy of the artist.

Tim Mara, The Black Room (1987). Silkscreen on paper. Collection of Durham University. Courtesy of the Tim and Belinda Mara Trust. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Paula Rego, Little Girl Series 1-8 (1989). Glazed ceramic tile. Collection of Durham University. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Édouard Vuillard, The Birth of Annette (1899). Lithograph on paper. Collection of Durham University. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Dorothea Wight, Plant in Green Bowl (date unknown). Mezzotint on paper. Collection of Durham University, Courtesy of the artist's estate. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Kraig Wilson, Joanne (2009). C-print photograph on Hahnemuhle paper. Collection of Durham University. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph by Mark Parham.

Anne Woolass, Interior (twentieth century). Etching on paper. Collection of Durham University. Photograph by Keith Orange.

Artist unknown, Girl at the Window (date unknown). Aquatint on paper. Collection of Durham University. Photograph by Keith Orange.