Jericho

An Ancient City Revealed

Camp at Tell es-Sultan; Photo by A.D. Tushingham. Courtesy of the NPAPH Project.

Camp at Tell es-Sultan; Photo by A.D. Tushingham. Courtesy of the NPAPH Project.

The site of Ancient Jericho, Tell es-Sultan, has a rich history spanning thousands of years. Excavations at the site by Kathleen Kenyon in the mid-1900s revealed significant finds, and Kenyon gave some of them to the Oriental Museum at Durham University so that visitors and researchers could continue to gain insight into past cultures.

The Oriental Museum holds over 100 artefacts from Ancient Jericho, including pottery, worked stones and metal. Through this collection, we are able to investigate the importance of Ancient Jericho as an archaeological site and use the objects to gain insight into life and death in these ancient cultures.

Click on the images below to view the objects in full screen!

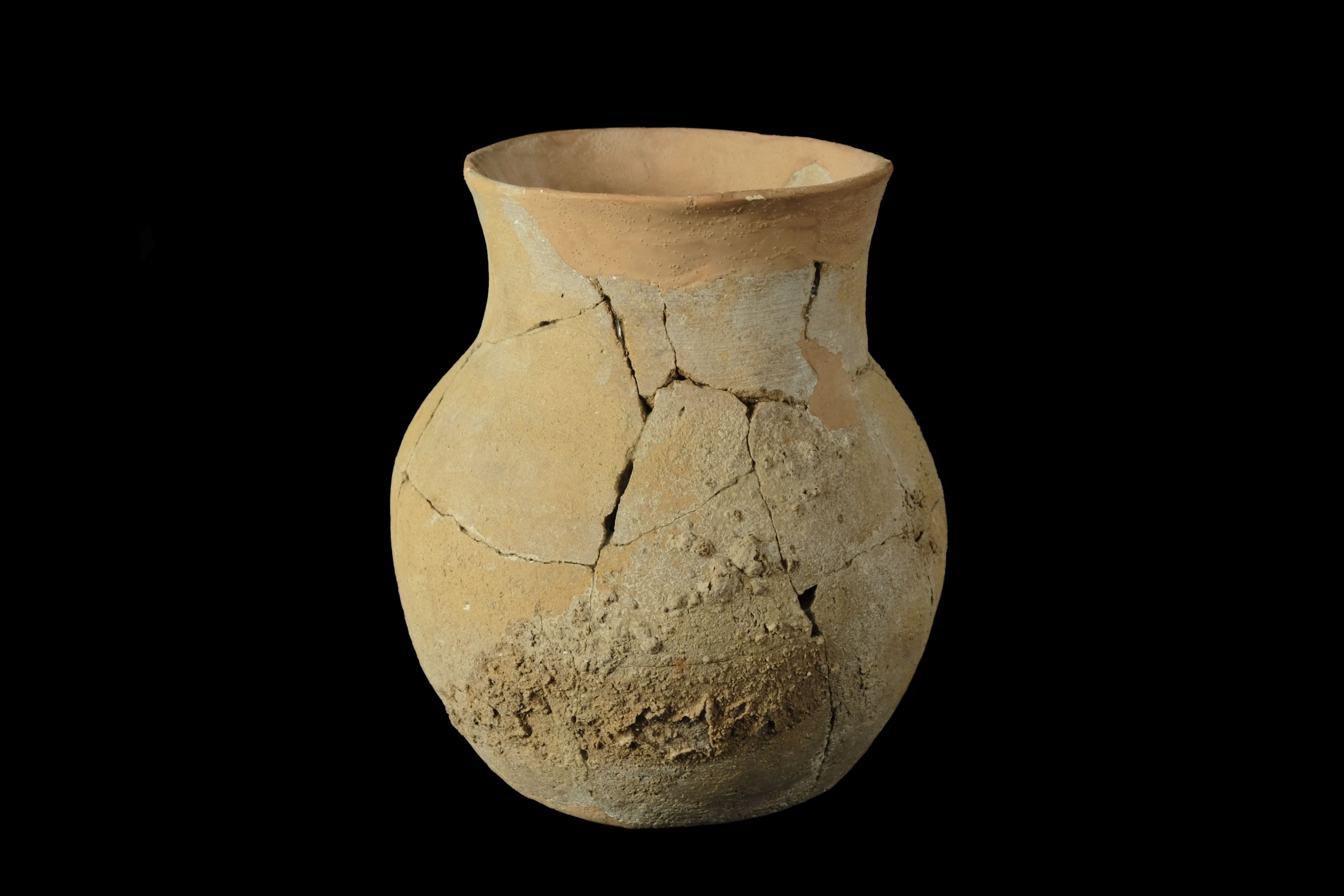

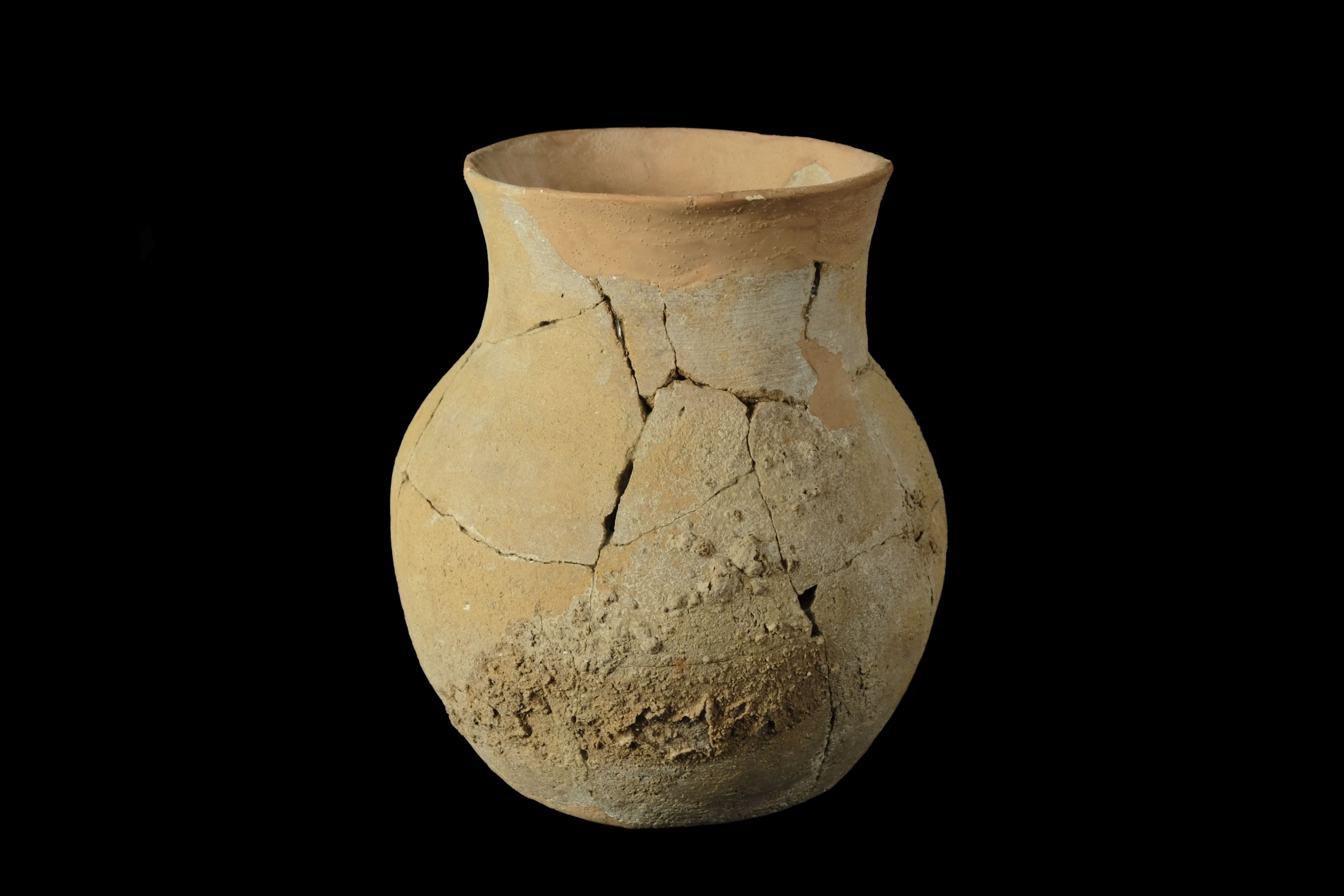

Jar | Ceramic | 2200-2000 BCE | DUROM.1964.352

Jar | Ceramic | 2200-2000 BCE | DUROM.1964.352

Buckle Fragments | Bronze | 2200-2000 BCE | DUROM.U10060

Buckle Fragments | Bronze | 2200-2000 BCE | DUROM.U10060

Pedestal vase | Ceramic | 2200-2000 BCE | DUROM.1964.342

Pedestal vase | Ceramic | 2200-2000 BCE | DUROM.1964.342

Dagger | Bronze | 2200-2000 BCE | DUROM.U10055

Dagger | Bronze | 2200-2000 BCE | DUROM.U10055

Pottery | Ceramic | Various dates | DUROM 1964. 349, DUROM 1964.500, DUROM 1964.354 , DUROM 1964.381

Pottery | Ceramic | Various dates | DUROM 1964. 349, DUROM 1964.500, DUROM 1964.354 , DUROM 1964.381

Shell | Unknown date | DUROM.U10061

Shell | Unknown date | DUROM.U10061

Amulet | Stone | 8800-6500 BCE | DUROM.U10042

Amulet | Stone | 8800-6500 BCE | DUROM.U10042

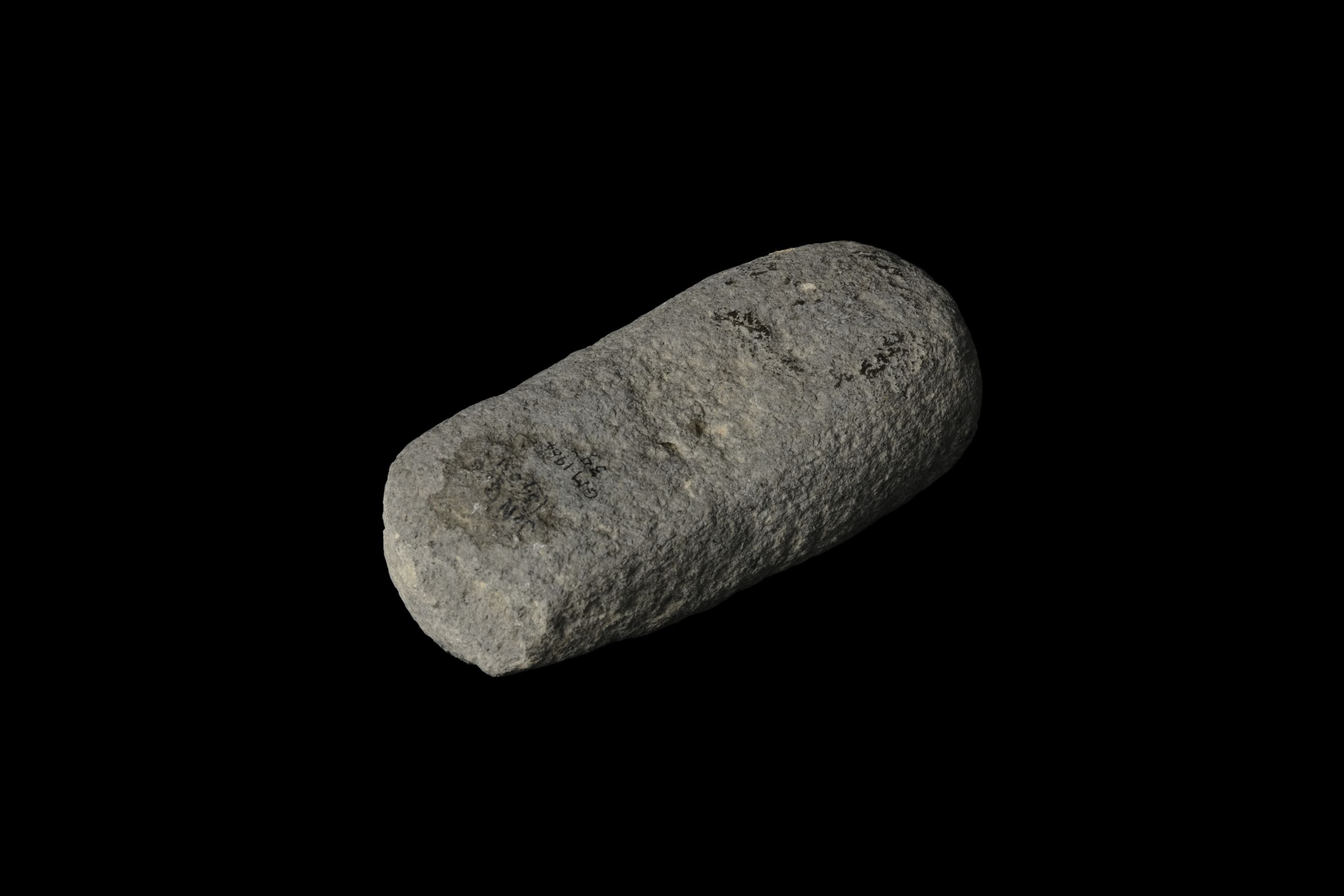

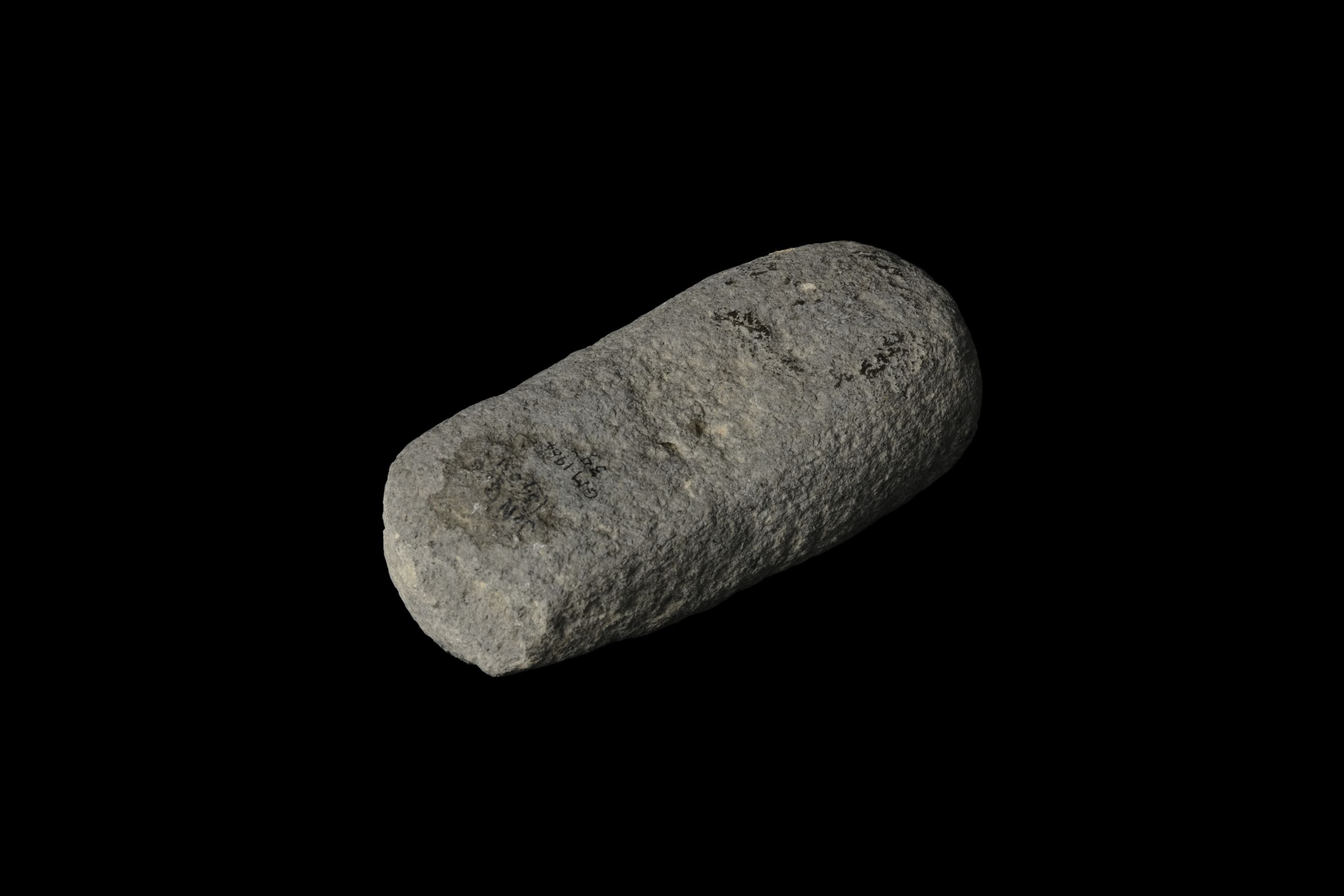

Pestle | Stone | 5000-1800 BCE | DUROM.1964.397

Pestle | Stone | 5000-1800 BCE | DUROM.1964.397

Legacies of British colonialism are evident in museum collections.

We would like to address this issue regarding this exhibition: the Ancient Jericho collections held in the Oriental Museum were donated by Kenyon herself, who had permission from the Jordanian Government to keep or distribute a portion of her findings to museums around the world. This exhibition does not intend to perpetuate colonial sentiment. It aims to showcase the archaeological, historic, anthropological and scientific value of the collection, and allow it to be accessible to all.

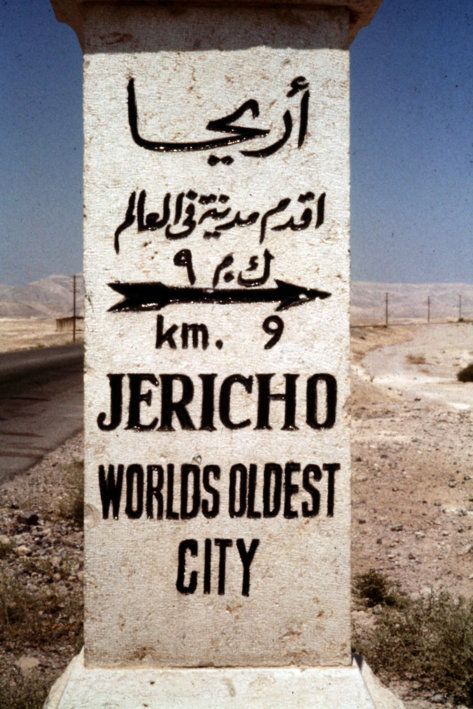

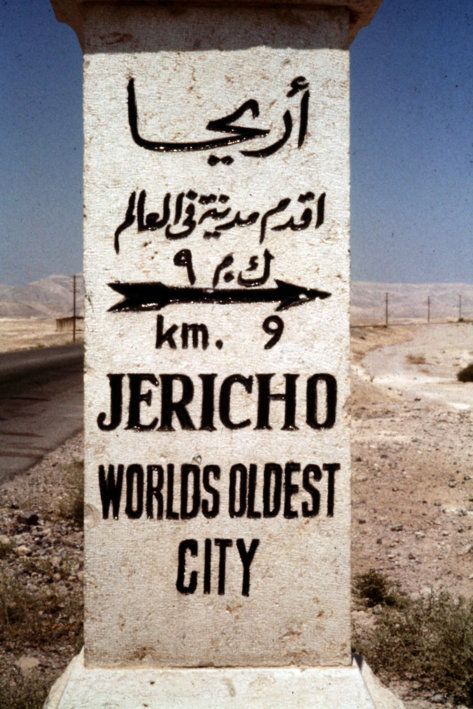

Where is Ancient Jericho?

The site of Ancient Jericho is located in West Asia, just outside the modern city of Jericho in Palestine.

As one of the oldest cities in the world, Ancient Jericho has long captured the attention of archaeologists. People first chose to settle in the area because of its fertile soil and warm weather, making it a perfect location for farming. Continuous settlement at the site over thousands of years has made it a great resource for learning about past lives.

Waymarker pointing to Jericho; Photo by A. D. Tushingham. Courtesy of the NPAPH Project.

Waymarker pointing to Jericho; Photo by A. D. Tushingham. Courtesy of the NPAPH Project.

Waymarker pointing to Jericho; Photo by A. D. Tushingham. Courtesy of the NPAPH Project.

The Archaeology of Ancient Jericho

Tell es-Sultan, the site of Ancient Jericho, is a tell site. A tell is a mound or small hill which has built up over centuries of activity. In this part of the world, villages and towns were built and rebuilt in the same location for hundreds or even thousands of years. New buildings were built on top of the ruins of earlier settlements which led to the ground level rising. Their long history means that tell sites can reveal to us a huge amount about the people who have lived there over thousands of years.

In the video below you can learn how a tell forms over time.

Inhabitants of Ancient Jericho

Tell sites such as Tell es-Sultan are useful to archaeologists. They can examine artefacts found in each layer to determine if people lived there and what their city might have looked like. Kathleen Kenyon found that at Tell es-Sultan there were up to 14 different phases of inhabitants who called Ancient Jericho home. They are grouped into 5 eras beginning almost 10,000 years ago.

Neolithic (8500-4600 BCE)

Ancient Jericho began as a town inhabited mainly by farmers. Neolithic people domesticated plants and animals, and kept their produce in large silos inside the town walls. The town was centred around a spring guarded by a tower. When an earthquake stopped or interrupted the water source, the inhabitants probably moved on and the area was uninhabited for around 1200 years.

Early Bronze Age (3400-2100 BCE)

Ancient Jericho became a fortified city during the Early Bronze Age. It was surrounded by wide walls and had a palace and a market where the inhabitants traded with other cities. Ancient Jericho was destroyed several times throughout the Early Bronze Age, either by military action or an earthquake, but each time was rebuilt even bigger.

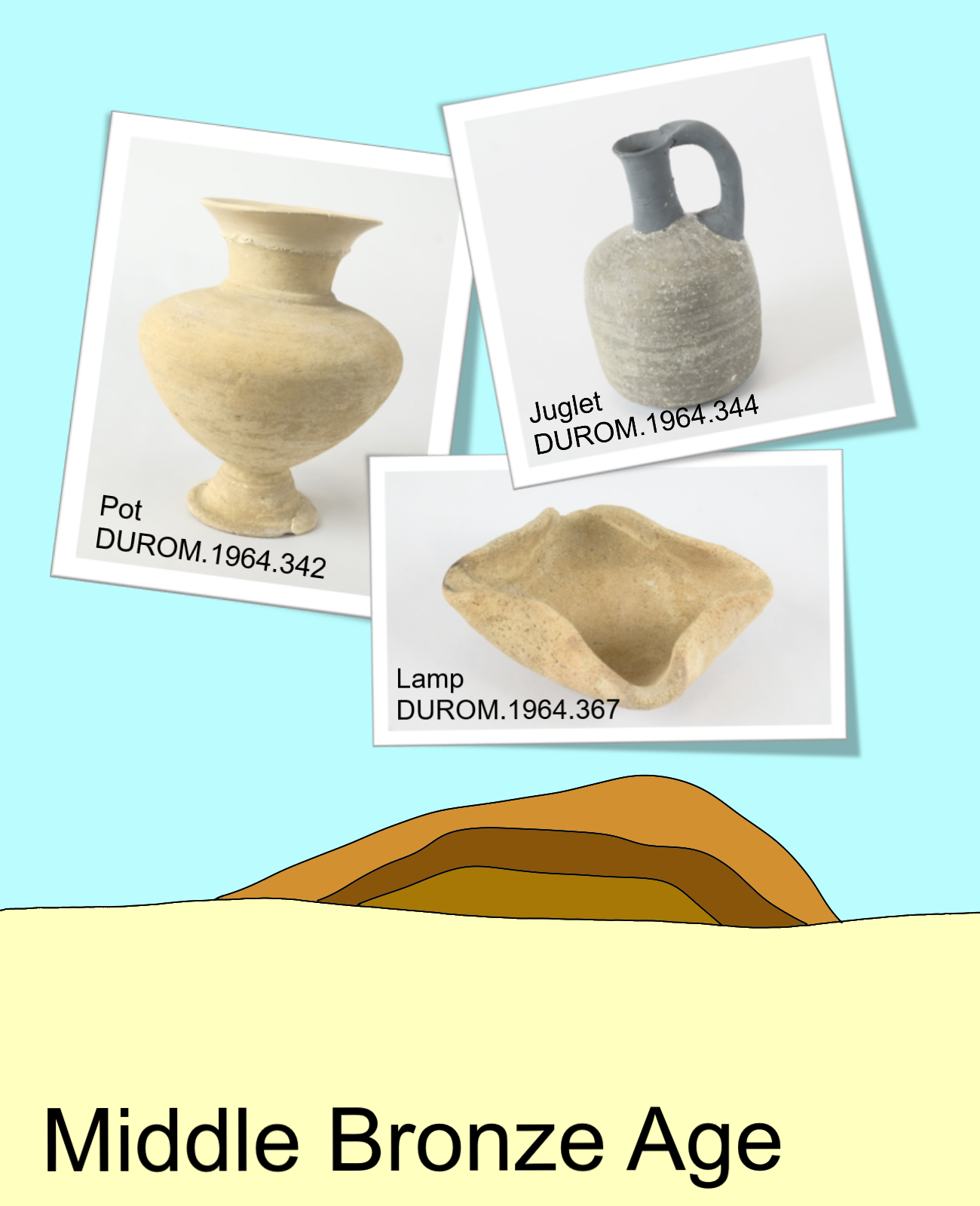

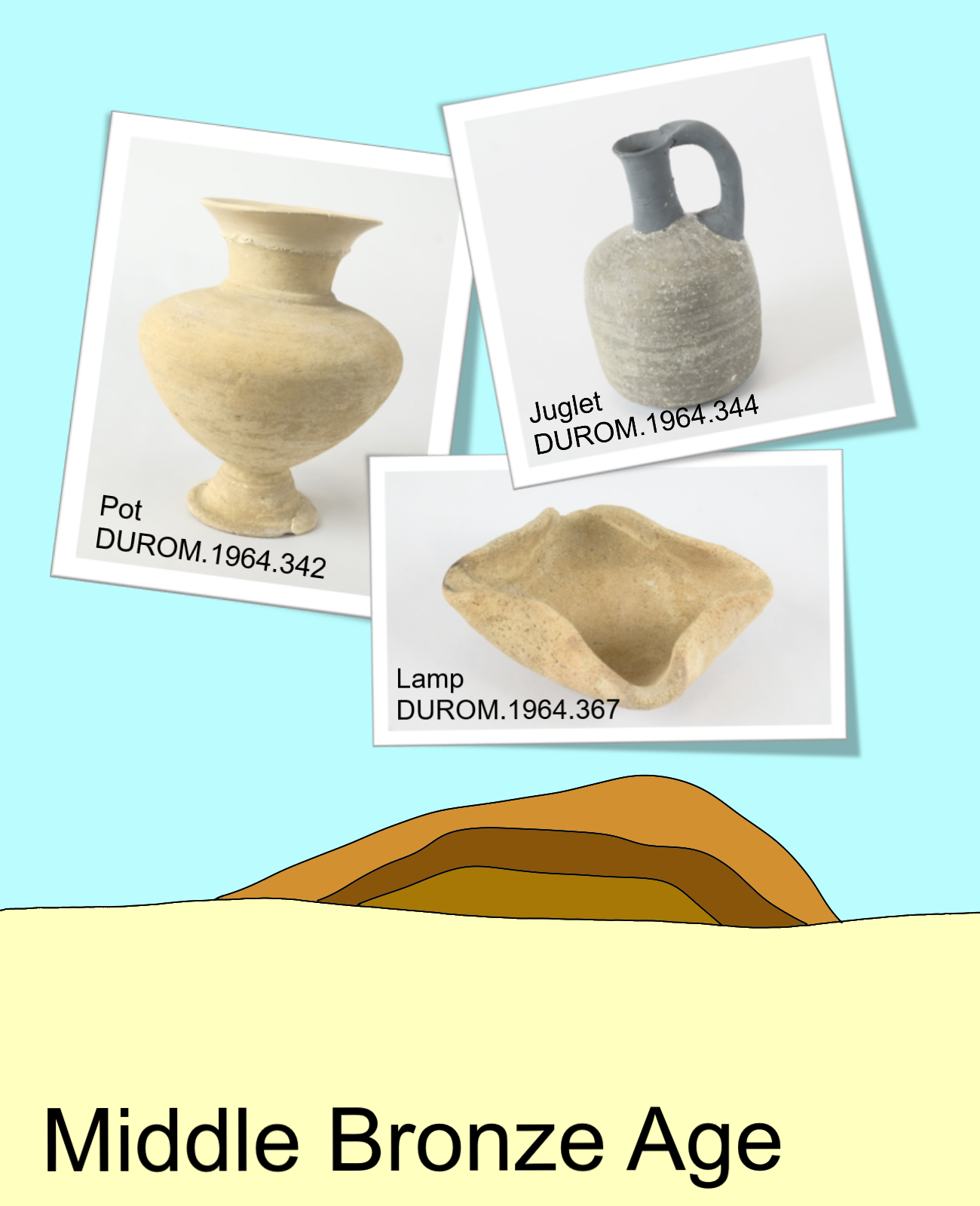

Middle Bronze Age (2100-1600 BCE)

During the Middle Bronze Age, the inhabitants built walls with defensive structures like towers and ramparts. There is evidence of military conflict throughout the period, possibly with the Ancient Egyptians. This age ended with the destruction of Ancient Jericho in a violent military action.

Late Bronze Age (1600-1200 BCE)

Archaeologists have found surprisingly few artefacts from the Late Bronze Age and suspect that most of the site was cleared by subsequent inhabitants. Although scant, the archaeological evidence does suggest that Late Bronze Age Jericho played an administrative role in the area, possibly even containing a palace and an archive.

Why do you think the artefacts were cleared by the people who inhabited Jericho after them?

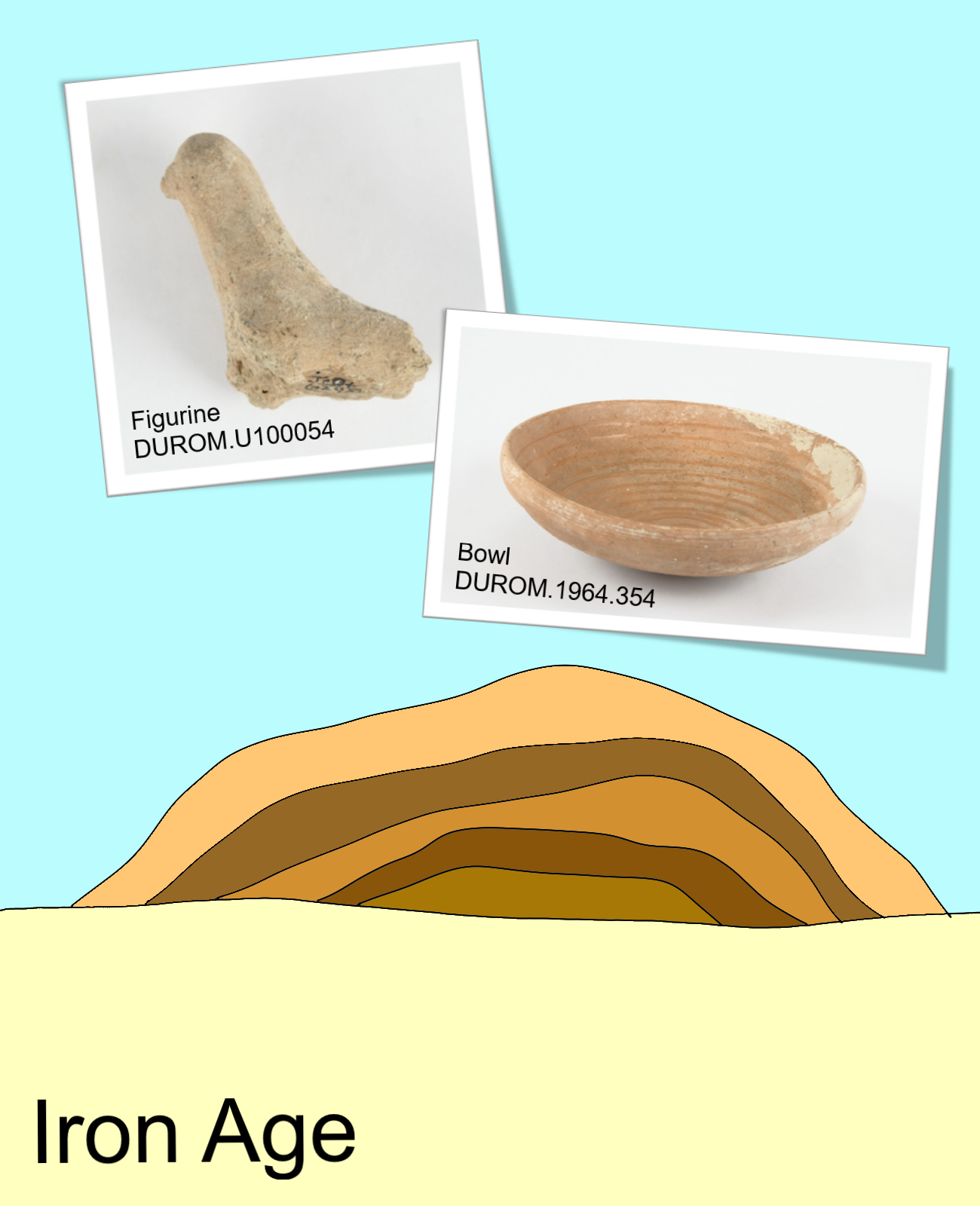

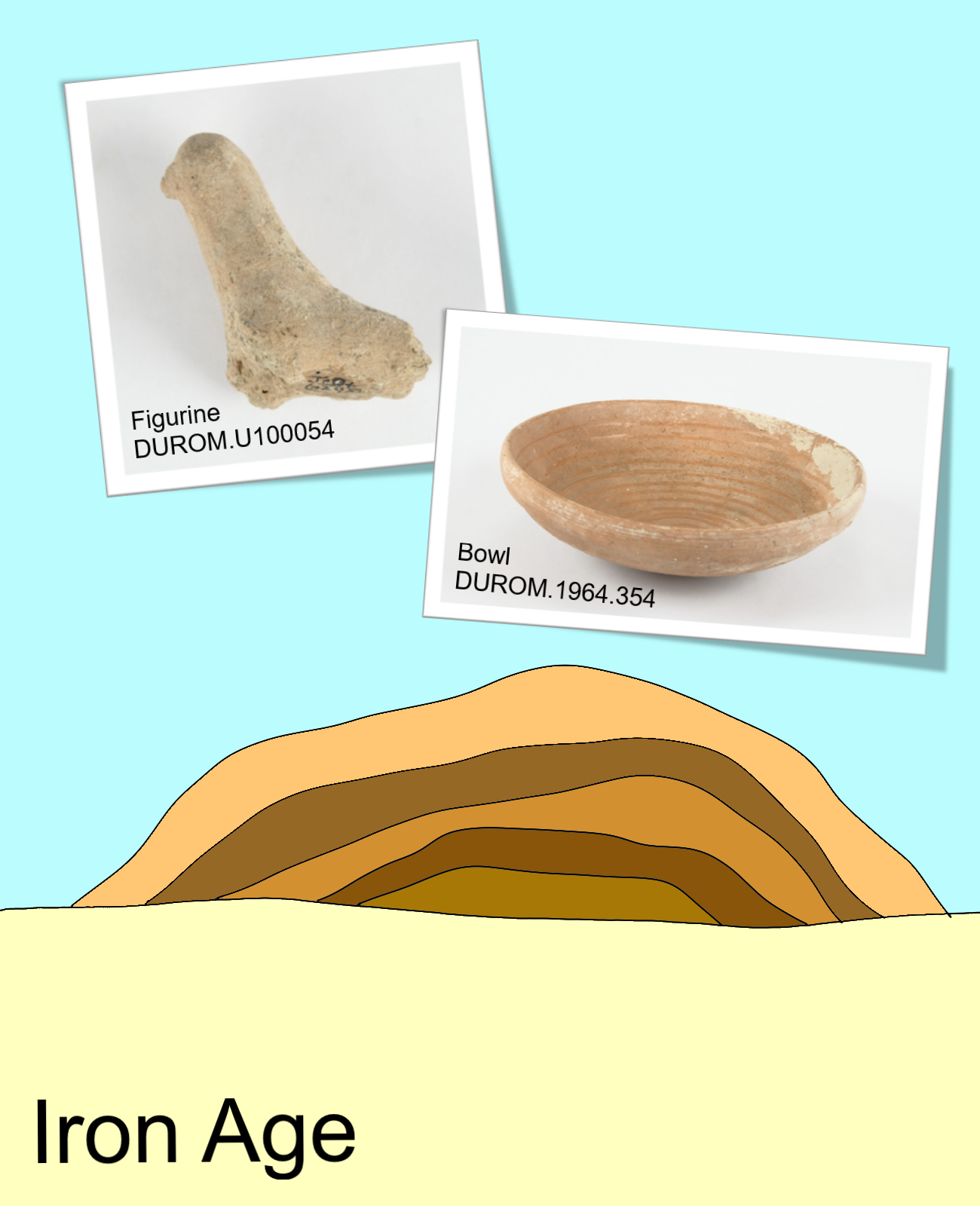

Iron Age (1200-500 BCE)

The last inhabitants of Ancient Jericho lived during the Iron Age. Compared to the other layers, archaeologists found fewer objects, which could indicate that the population was smaller. Nevertheless, Ancient Jericho was still an important city, as there is evidence of cultural interaction with other cities. Iron Age Jericho was located at the top of the tell and had to be reached by staircases cut into the side of the mound.

Because of the lack of artefacts recovered from the top layers of Tell es-Sultan, archaeologists conclude that there was little activity after the Iron Age. The artefacts in the layers of the tell make it a valuable resource for archaeologists who have been excavating there for over 150 years.

Kathleen Kenyon's Excavations at Jericho

Kathleen Kenyon was a pioneering female archaeologist whose excavations at Tell es-Sultan were extremely important to the development of modern archaeology. She excavated there from 1952 to 1958.

Kenyon's work led to the site being dated as one of the oldest cities in the world and set a new standard for archaeological excavation.

Dame Kathleen Mary Kenyon; Photo by Elliot & Fry (1962). © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Dame Kathleen Mary Kenyon; Photo by Elliot & Fry (1962). © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Kathleen Kenyon; Photo by A. D. Tushingham. Courtesy of the NPAPH Project.

Kathleen Kenyon; Photo by A. D. Tushingham. Courtesy of the NPAPH Project.

Dame Kathleen Kenyon

Dame Kathleen Mary Kenyon; Photo by Elliot & Fry (1962). © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Born on 5 January 1906, Kathleen Kenyon was the eldest daughter of Sir Frederic Kenyon, the director of the British Museum from 1909 to 1930.

As a student at Oxford University, she was elected the first chairwoman of the Oxford University Archaeological Society.

After graduating, Kenyon had her first field experience in an archaeological expedition to Great Zimbabwe, Africa. She then joined the renowned archaeologists Mortimer and Tessa Wheeler to excavate Verulamium, a Roman town in St Albans, England. There she learned the Wheeler stratigraphic excavation method, a technique she would later refine in her excavations at Ancient Jericho.

Kenyon worked on many sites in Africa, Britain and West Asia and was one of the most influential female archaeologists at the time.

Kathleen Kenyon; Photo by A. D. Tushingham. Courtesy of the NPAPH Project.

Over the course of her life she held important positions such as acting director of the University of London Institute of Archaeology, director of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and principal of St. Hugh’s College, Oxford.

In 1973 she was appointed a Dame of the British Empire for her services to archaeology.

Kenyon died on 24 August 1978, at the age of 72.

'...this legendary figure is a confident, stout, middle-aged woman with intense blue eyes, a low-pitched throaty voice, striding manfully up and down the mound in the battered trench coat she would wear throughout the Jericho excavations, a cigarette ever-present in her nicotine-stained hand or mouth, alerting the loafing basket boys to her imminent presence by her rattling smokers' cough... the woman who could bend over at the waist and pick up and examine pieces of pottery without bending her knees.'

- M. Davis, Dame Kathleen Kenyon: Digging Up the Holy Land (2008)

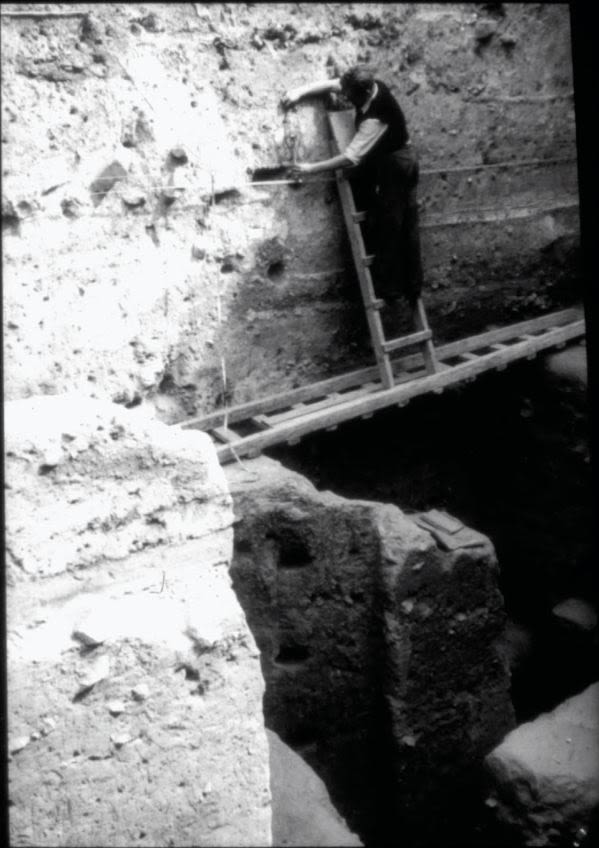

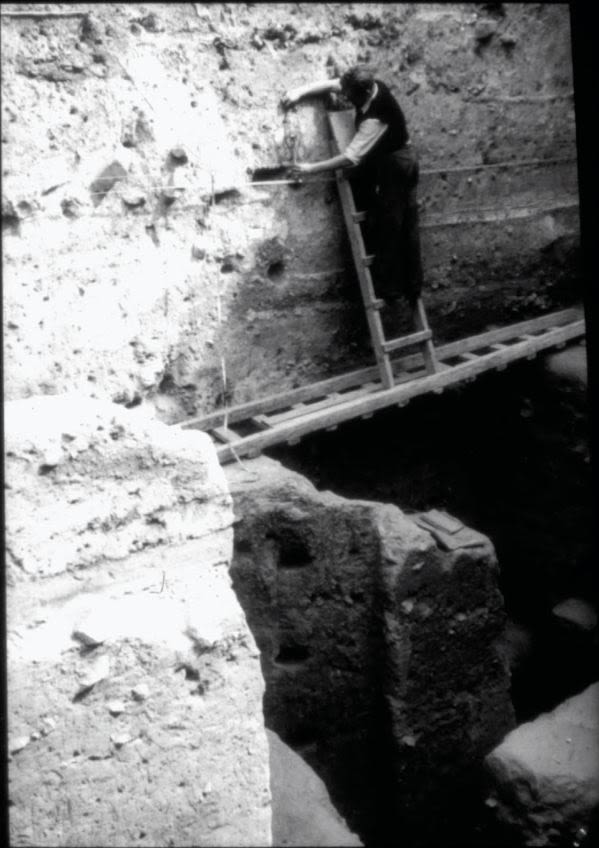

An archaeologist examining strata in the baulks; Photo by Dorothy Marshall. Courtesy of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London.

An archaeologist examining strata in the baulks; Photo by Dorothy Marshall. Courtesy of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London.

‘Mistress of Stratigraphy’

Kenyon became known as the ‘Mistress of Stratigraphy’ because of her work at Tell es-Sultan. But how did Kenyon excavate Ancient Jericho, and why was her method so important?

An archaeologist examining strata in the baulks; Photo by Dorothy Marshall. Courtesy of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London.

What is Stratigraphy?

The video above showed how tell sites like Ancient Jericho were formed through layers of settlement. If you sliced through the tell, you would be able to see the series of layers (‘strata’). Each of these strata represents a period in the site’s history, with the strata being older the deeper they are. Stratigraphy is the method of excavating the site according to the strata, digging down layer by layer.

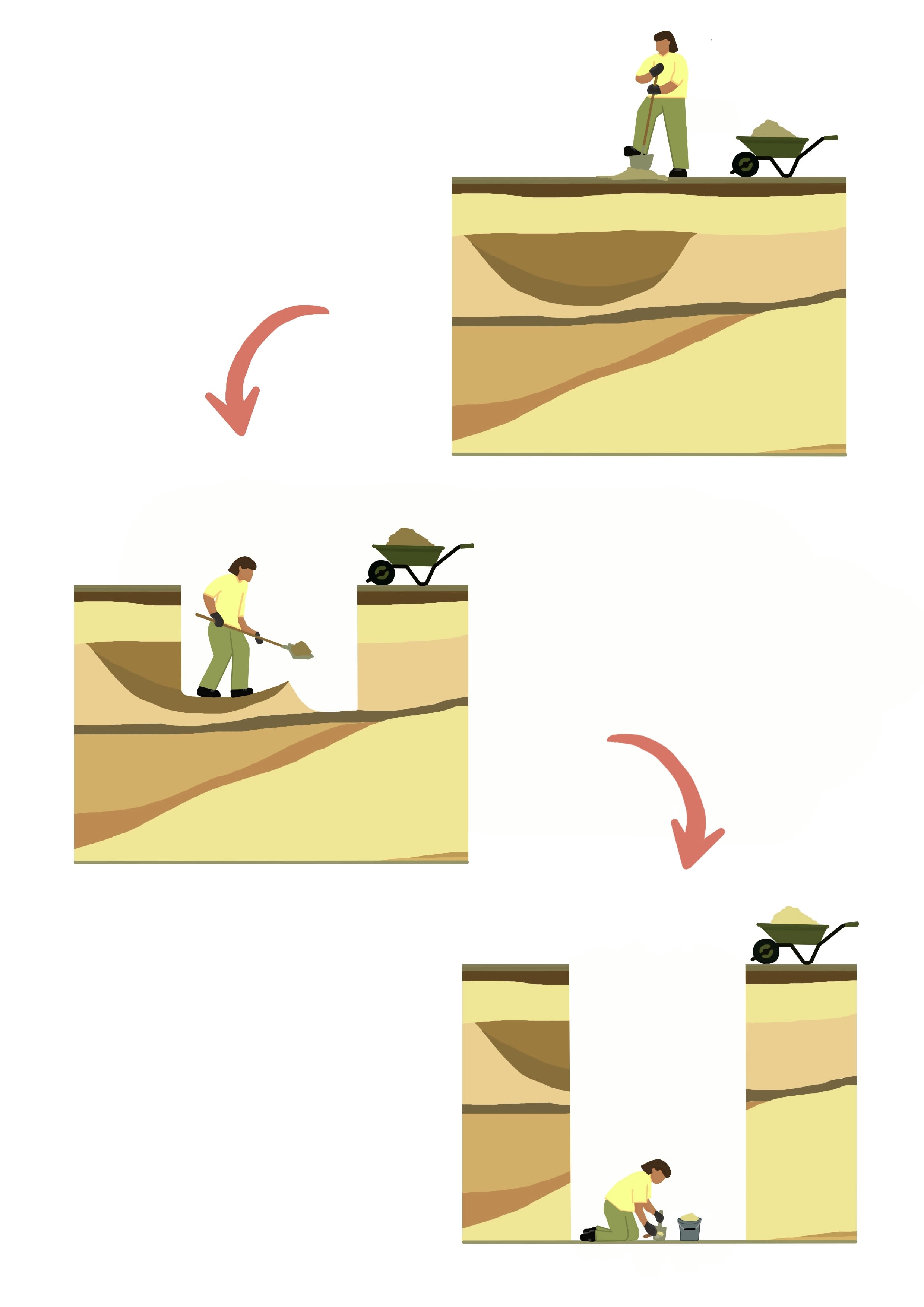

Excavating according to strata

Excavating according to strata

Previous excavations at Ancient Jericho did not consider stratigraphy. For example, Garstang’s approach only looked at evidence of buildings and ignored stratigraphy and pottery finds. These older techniques made it impossible to precisely date and interpret stages of architecture.

Kenyon’s Technique

Kenyon realised that using stratigraphy could help her to understand the site better.

She was familiar with the 'Wheeler box method' from her time excavating with Mortimer and Tessa Wheeler. Kenyon refined this method at Ancient Jericho to create what became known as the 'Wheeler-Kenyon method'.

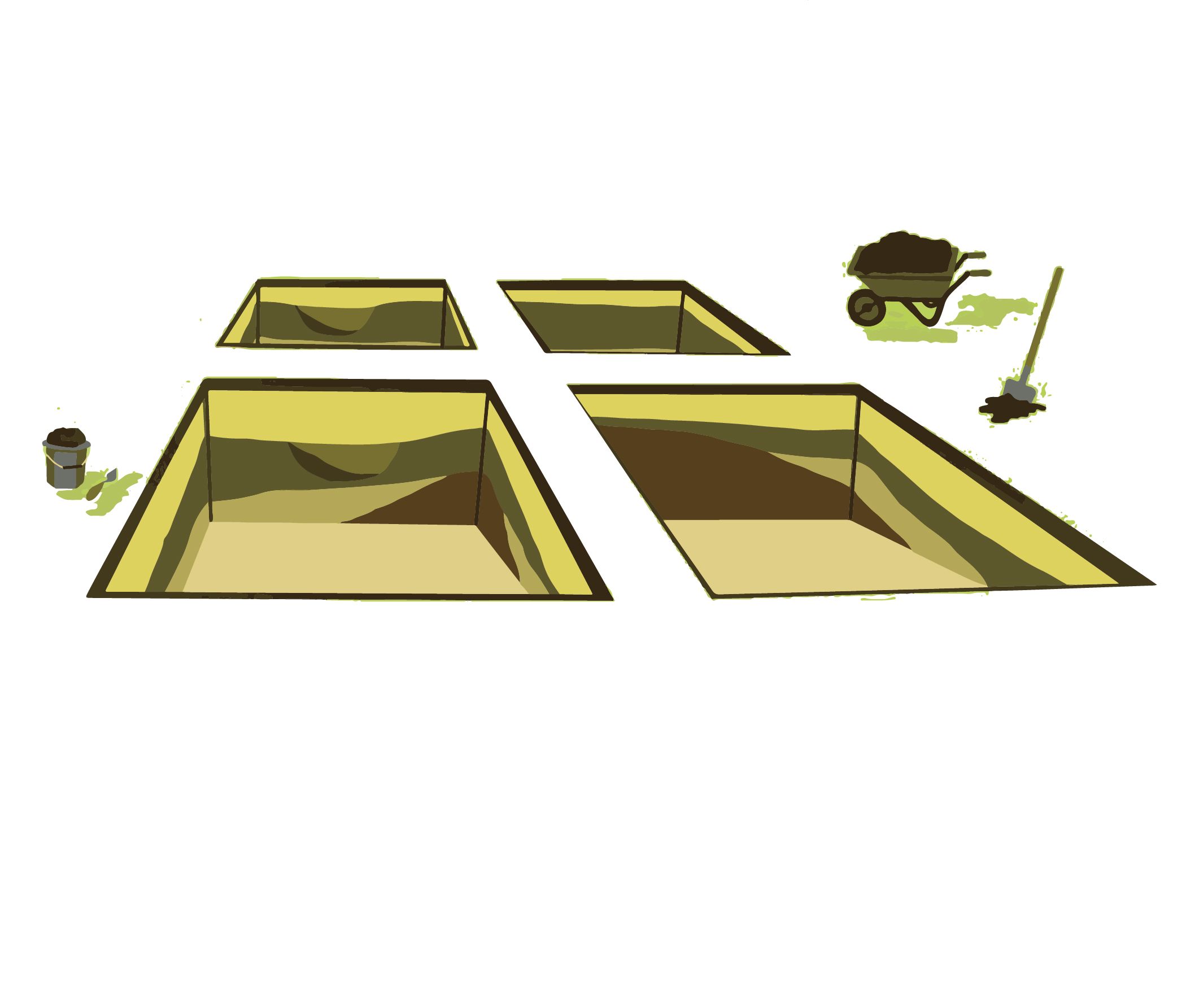

A ‘Wheeler box’ was a five by five metre square trench with spaces left between the digging areas called baulks. The baulks left between the trenches allowed archaeologists to record the strata.

'Wheeler boxes'

'Wheeler boxes'

At Tell es-Sultan, the topography of the site (the shape of the land) meant uniform squares would not work - the ground was too uneven. Instead, Kenyon moved beyond the uniform grid of square trenches, adapting the size and shapes of the trenches to the site.

Kenyon was strict about the sides of the trenches being perfectly straight so she could see the stratigraphy clearly. This meant that the workers were not allowed to dig sideways - even to retrieve artefacts!

Studying the stratigraphy helped Kenyon to understand how the site formed and to identify patterns of construction, use and abandonment of buildings. This allowed a greater understanding of the stages of settlement at Ancient Jericho and how the tell grew and changed over time.

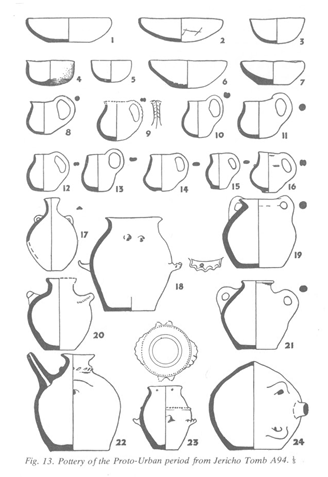

As well as the technique of stratigraphy, Kenyon also fine-tuned the study of excavated pottery. She looked not only at complete pots, as most excavators before her had done, but also at the many sherds (broken pottery fragments) found in each excavated layer.

Click on the images below to view the objects in full screen!

Juglet | Ceramic | Unknown date | DUROM.1964.514

Juglet | Ceramic | Unknown date | DUROM.1964.514

Vessel | Ceramic | 2700-2200 BCE | DUROM.1964.507

Vessel | Ceramic | 2700-2200 BCE | DUROM.1964.507

Bowl | Ceramic | Unknown date | DUROM.1964.494

Bowl | Ceramic | Unknown date | DUROM.1964.494

Bowls | Ceramic | 2700-2200 BCE | DUROM.1964.492, DUROM.1964.533, DUROM.1964.530

Bowls | Ceramic | 2700-2200 BCE | DUROM.1964.492, DUROM.1964.533, DUROM.1964.530

Juglet handle | Ceramic | Unknown date | DUROM.1964.517

Juglet handle | Ceramic | Unknown date | DUROM.1964.517

Excavation Site; Photo by A. Searight. Courtesy of the NPAPH Project.

The Excavations

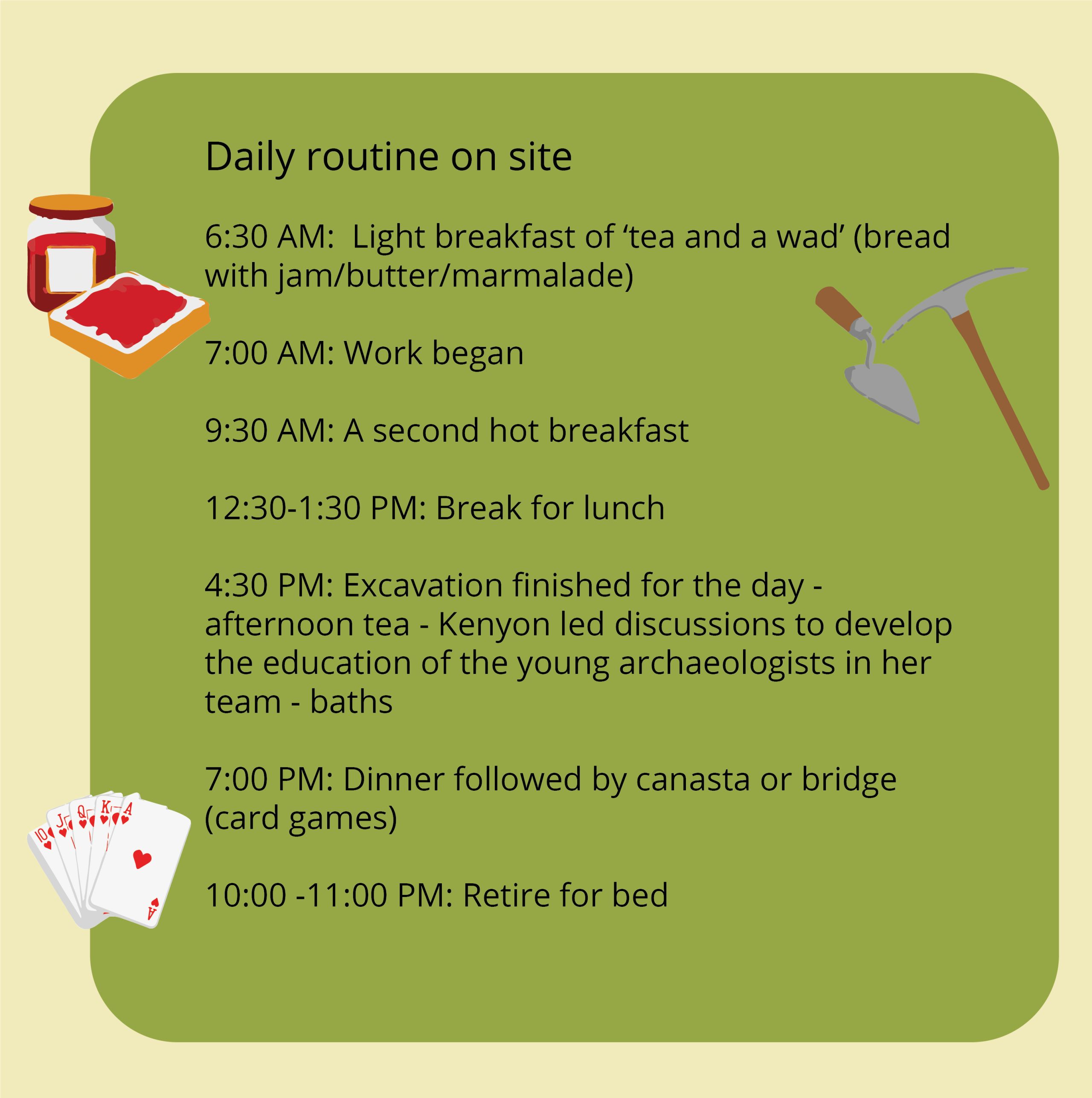

What was supposed to be a small excavation of Tell es-Sultan lasted for almost 7 years, from 1952 to 1958.

Kenyon and her small team supervised the site while a large team of local men were hired to do the digging. Kenyon employed local people to work on the site, providing jobs which helped a community suffering with poverty and unemployment. Some of the workmen were Palestinian Arab refugees who were displaced from Israel during the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Excavation Process

Each supervisor’s team had a pick man, multiple shovel men to dig and basket boys who took the earth away.

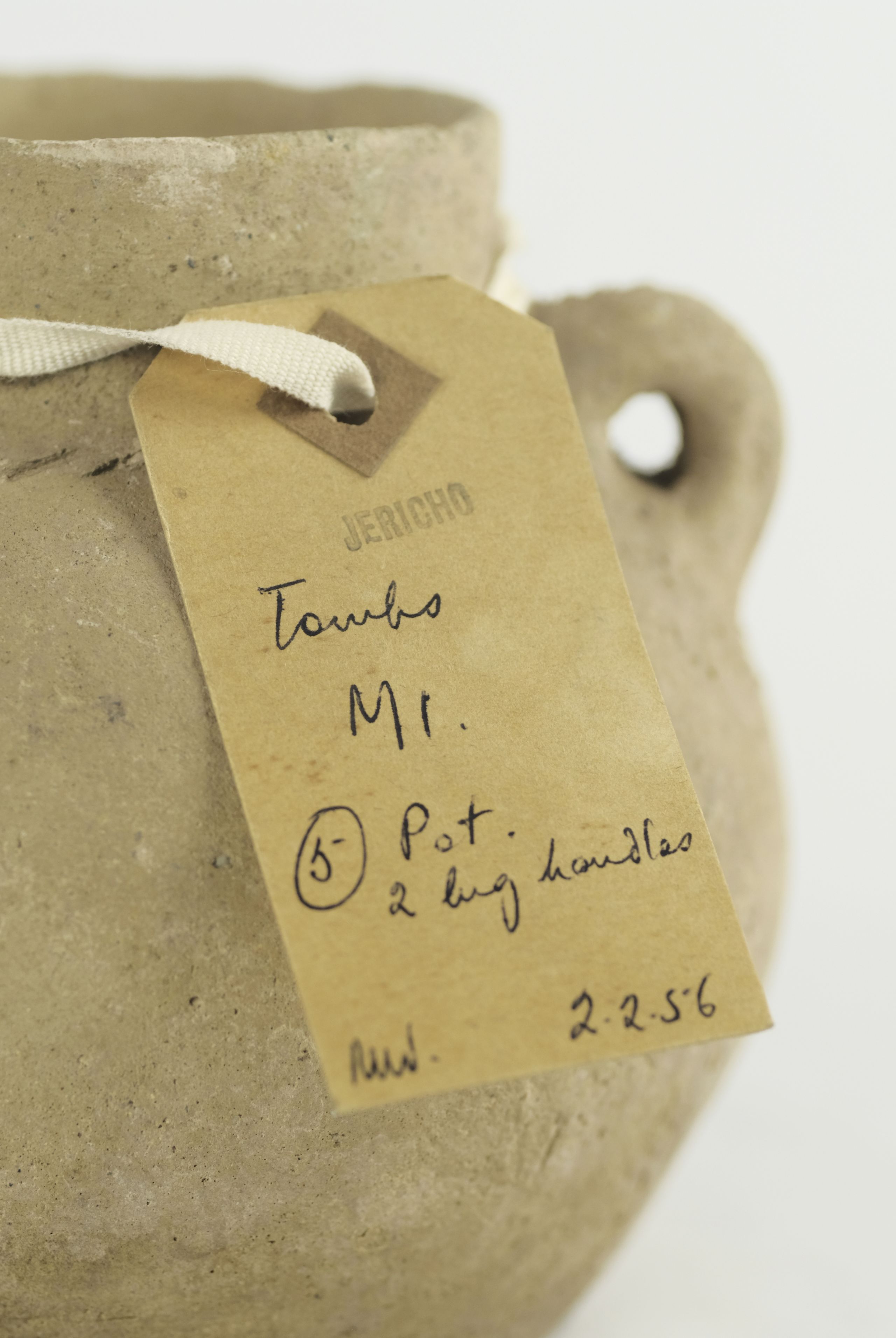

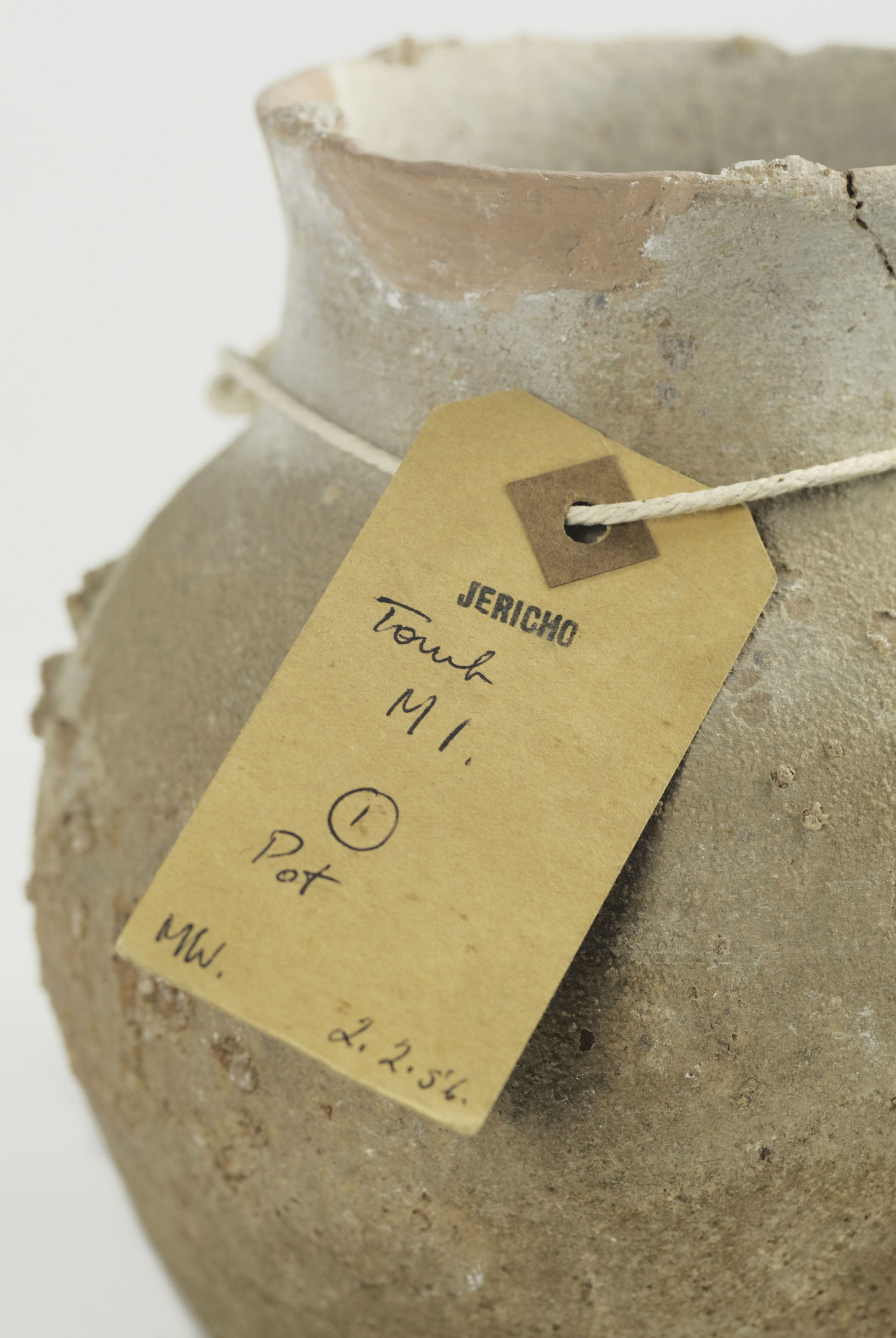

First, the workmen removed the soil. Then the supervisor recorded what was found in each layer of earth and any changes in the colour or texture of the soil.

All the pottery sherds recovered were placed in a basket marked with the layer in which they were found.

The baskets were taken to the dig headquarters where the sherds were sorted, washed, and laid out on mats to dry. Registrars marked each sherd with the identifying number of the strata and trench it came from.

Kenyon chose the pottery she wanted to look at more closely: usually sherds with identifiable features like rims, bases and handles, or distinctive decorations.

The classification of pottery based on its forms and features would allow the Jericho pots to be compared with those found at other sites to determine when they were made.

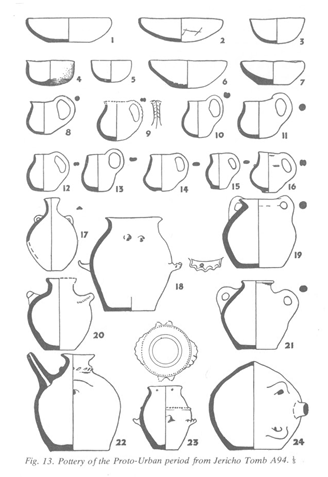

Excerpt from the Archaeology Reports; from: Archaeology in the Holy Land, 4th Edition by Kathleen M. Kenyon, Copyright (1979) by Ernest Benn Limited. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis Group.

Using these methods, Kenyon could date buildings and structures on the site.

Kenyon found that the defensive walls identified by Garstang were in the same strata as Early Bronze Age pottery, which shows the walls and pottery were in use at the same time. This means the walls were also from the Early Bronze Age, 2000 years earlier than Garstang estimated.

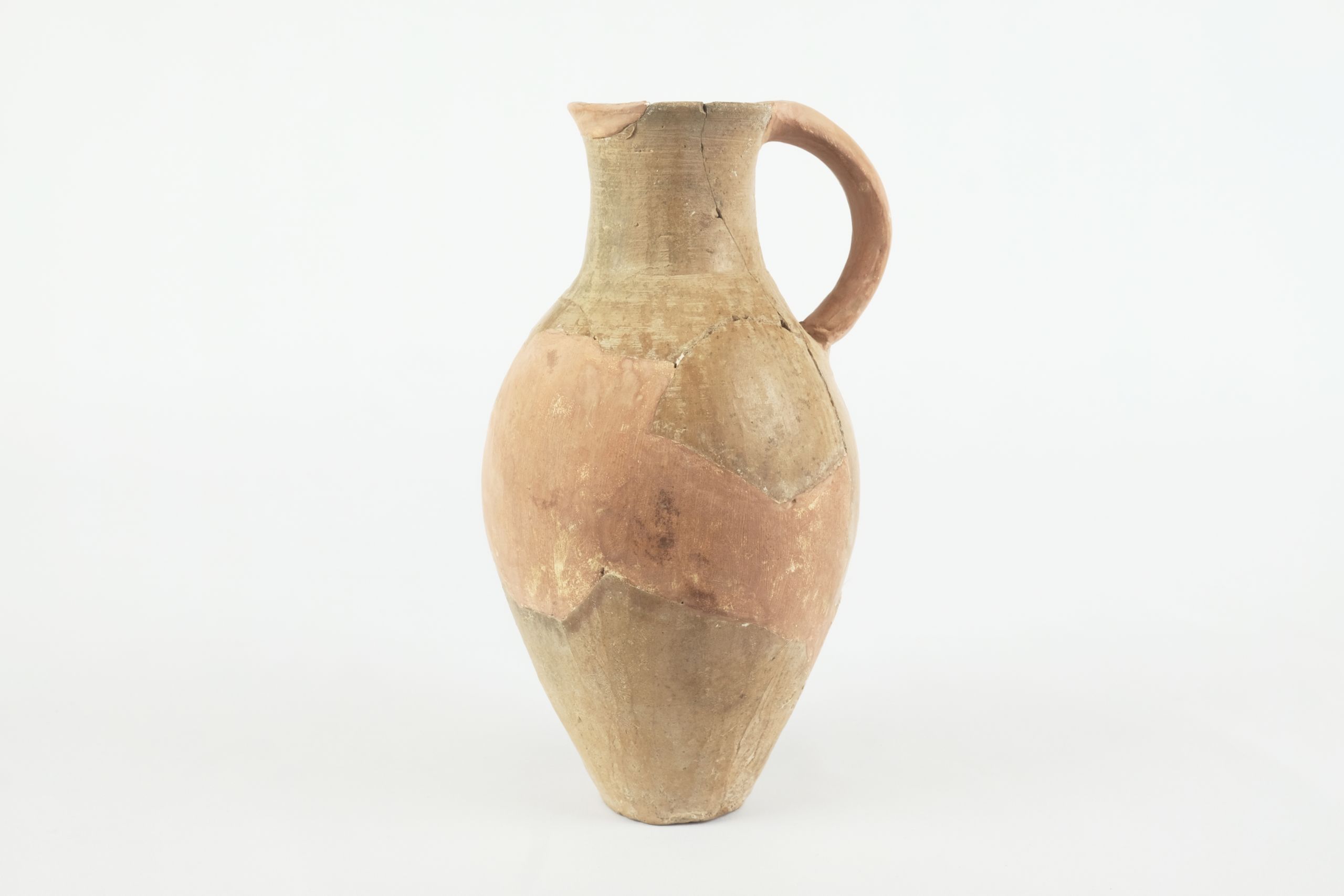

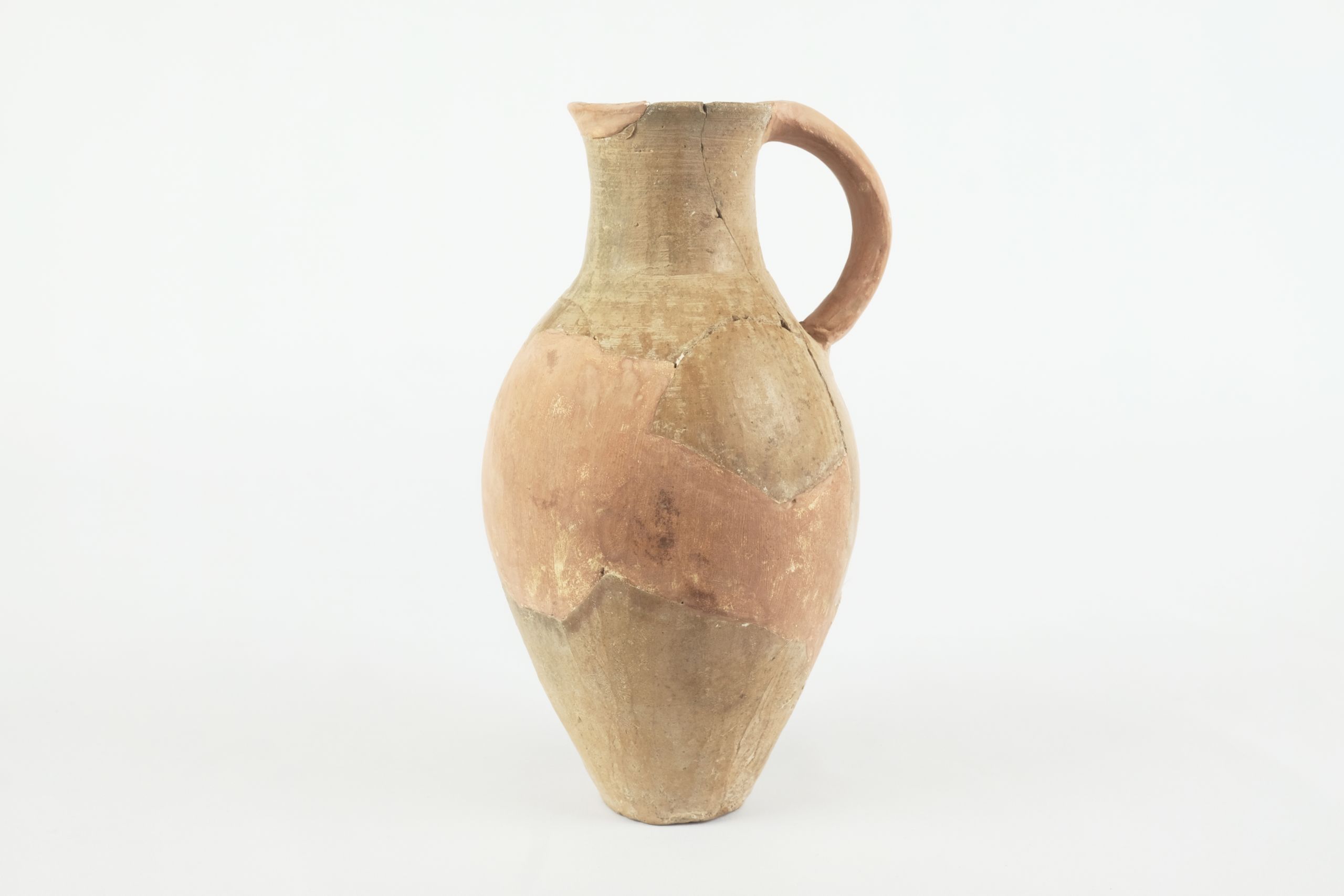

Pottery Reconstruction

Many excavated pottery sherds could be pieced together and reconstructed as whole pots, like a 3-D puzzle. Using their knowledge of ancient pottery, the conservators reconstructed the missing parts with plaster of Paris coloured to match the pot.

Can you spot the areas where the following pots have been reconstructed? Click on the images to view the objects in full screen!

Excavation Site; Photo by A. Searight. Courtesy of the NPAPH Project.

Excavation Site; Photo by A. Searight. Courtesy of the NPAPH Project.

Excerpt from the Archaeology Reports; from: Archaeology in the Holy Land, 4th Edition by Kathleen M. Kenyon, Copyright (1979) by Ernest Benn Limited. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis Group.

Excerpt from the Archaeology Reports; from: Archaeology in the Holy Land, 4th Edition by Kathleen M. Kenyon, Copyright (1979) by Ernest Benn Limited. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis Group.

Jug | Ceramic | 2700-2200 BCE | DUROM.1964.537

Jug | Ceramic | 2700-2200 BCE | DUROM.1964.537

Pot | Ceramic | 2700-2200 BCE | DUROM.1964.362

Pot | Ceramic | 2700-2200 BCE | DUROM.1964.362

Jug | Ceramic | 2700-2000 BCE | DUROM.1964.363

Jug | Ceramic | 2700-2000 BCE | DUROM.1964.363

Juglet | Ceramic | 2100-1600 BCE | DUROM.1964.344

Juglet | Ceramic | 2100-1600 BCE | DUROM.1964.344

Jug | Ceramic | Unknown date | DUROM.1964.370

Jug | Ceramic | Unknown date | DUROM.1964.370

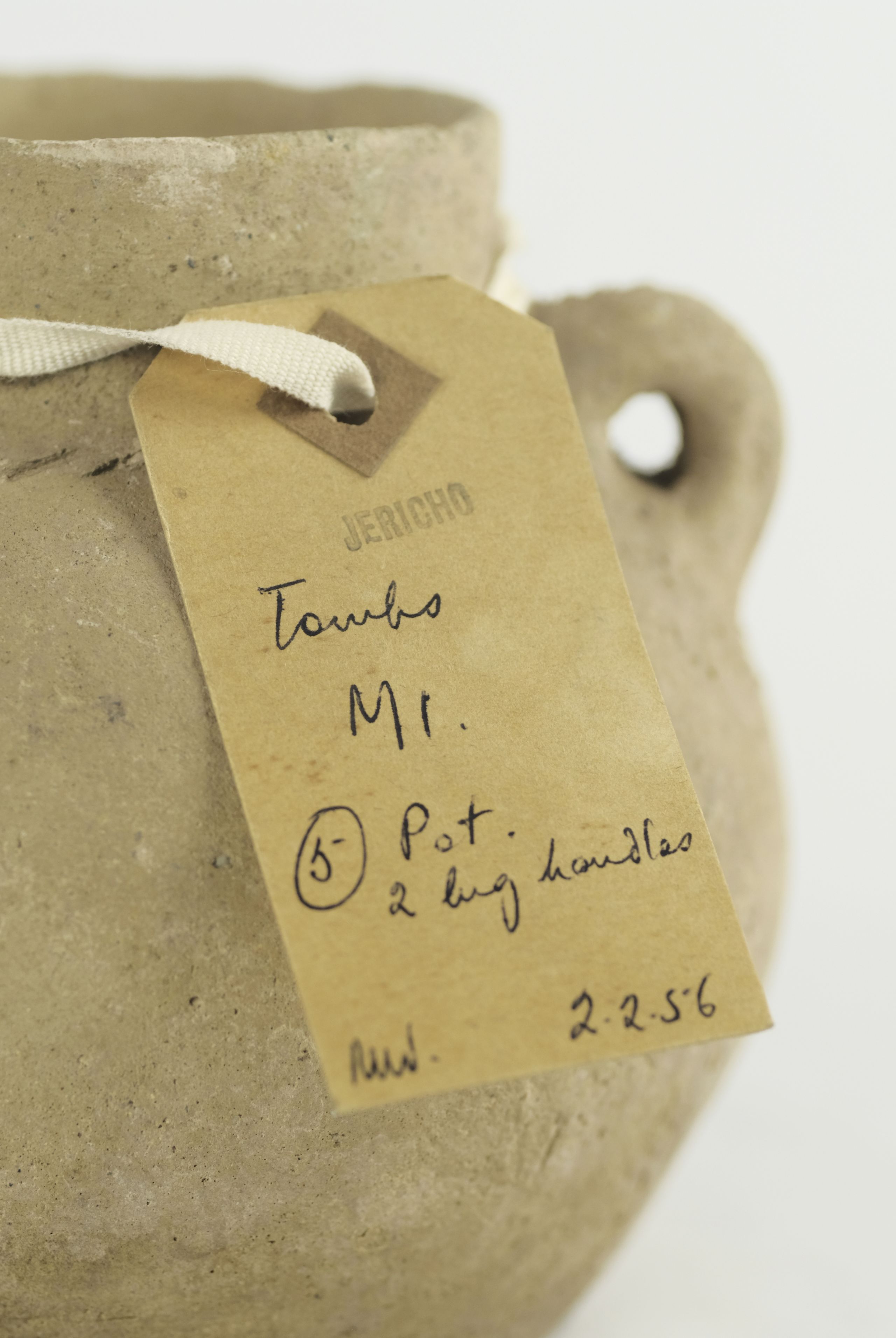

Original artefact label from the excavations | 1952-58 | OM archive

Original artefact label from the excavations | 1952-58 | OM archive

Original artefact labels from the excavations | 1952-58 | OM archive

Original artefact labels from the excavations | 1952-58 | OM archive

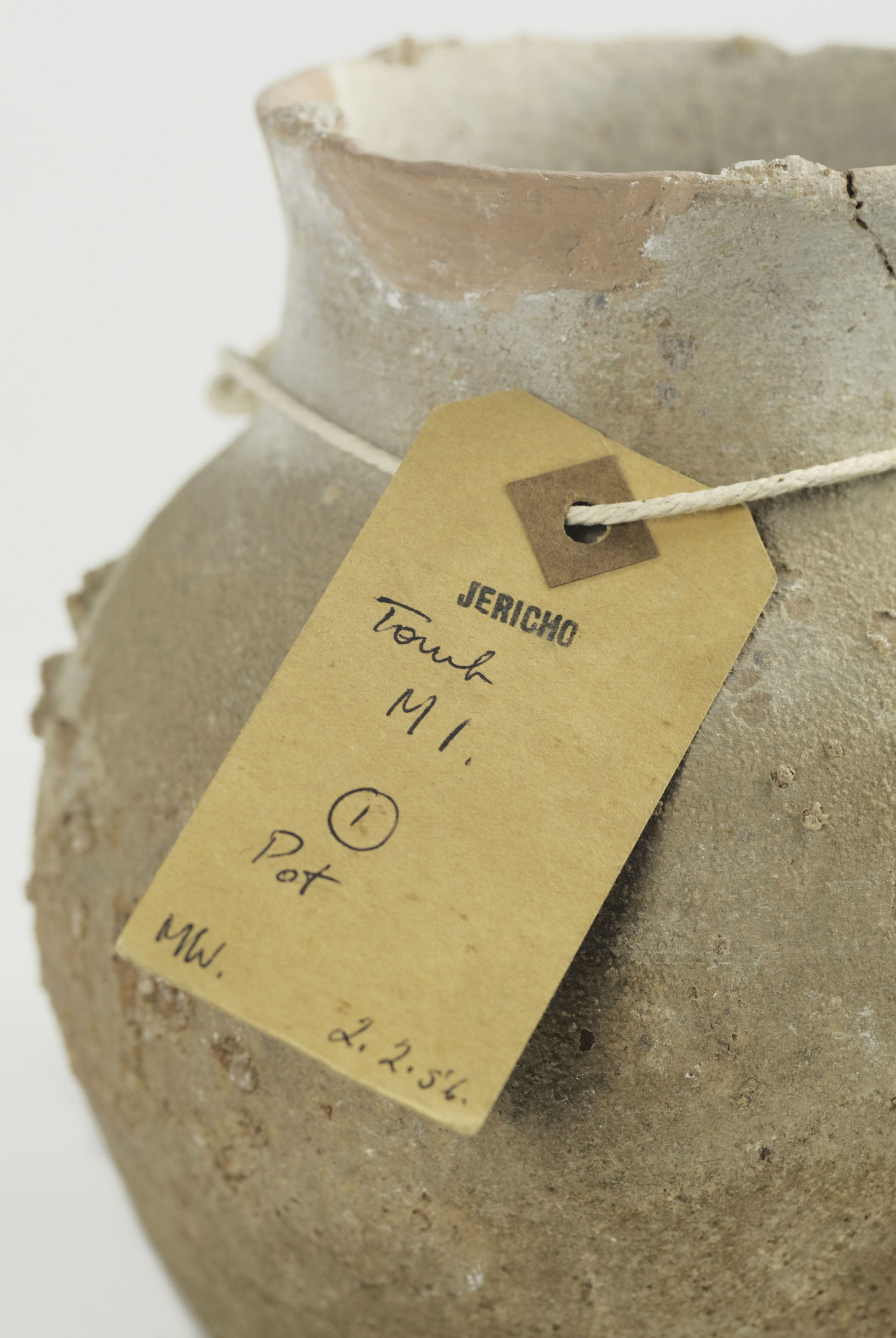

Original artefact label | 1952-58 | OM archive

Original artefact label | 1952-58 | OM archive

Activity at the site continues to this day.

Since Kenyon, the Italian-Palestinian Expedition has conducted excavations between 1997-2017, building on her pioneering techniques and unearthing more finds.

The expedition has preserved and restored Tell es-Sultan as a field school for young archaeologists and still promotes it as a tourist attraction. Through their 'Jericho Oasis Archaeological Park', the expedition also continues to exhibit Kenyon's horizontal and vertical stratigraphic layers.

Life and Death in Ancient Jericho

Have you ever wondered how archaeologists use the artefacts they find to reconstruct how people lived?

Archaeologists take into account where an object is found, what it could be used for, its condition and the other things they find with it. With this information, they can sometimes make a guess as to how the ancient city might have looked.

At Ancient Jericho, Kenyon’s excavation revealed many fascinating artefacts from both homes and tombs. These objects are indicators of a life that someone once lived. In this section, you can experience life and death in Ancient Jericho through a tour of a reconstructed home and tomb based on Kenyon’s finds and excavation reports.

Click on the objects to learn more about how they fit into everyday life in Ancient Jericho!

These artefacts can still tell us more about these ancient cultures.

By using techniques like Kenyon’s stratigraphic method, archaeologists are able to better understand how an artefact fits into a site and how people might have lived their day-to-day lives.

The Oriental Museum staff are dedicated to ensuring that these and thousands of other artefacts are available for researchers now and in the future.

The MA Museum and Artefact Studies students behind this project

The MA Museum and Artefact Studies students behind this project

Acknowledgements

This exhibition was created by the students of the MA Museum and Artefact Studies 2020-21 in Durham University’s Department of Archaeology.

The MA Museum and Artefact Studies students behind this project

We are grateful to everyone who made this exhibition possible.

Our thanks go to: the interviewees for our podcast series, Felicity Cobbing (Chief Executive & Curator of the Palestine Exploration Fund) and Professor Robin Skeates (Department of Archaeology, Durham University); the community members who contributed to our audience research; and the volunteers of the focus group for their feedback on graphics.

Thanks also go to the organisations who assisted with our research: Durham University School of Modern Languages & Cultures; Michael Stansfield, Andrew Gray and all the staff at Palace Green Library, Durham University; and the Palestine Exploration Fund, London.

We would like to thank the Oriental Museum for allowing us access to their collection and special thanks goes to the team at Durham University Museums who supported and advised us throughout the development of this project: Rachel Barclay, Gillian Ramsay, Ross Wilkinson, David Wright and our Museum Communication Module Convenor, Dr Mary Brooks.

We would also like to thank all the other staff for their contributions to the creation of this exhibition, including: Helen Armstrong, Craig Barclay, Joanne Coe, Julia Oliver and Charlotte Spink.

Thanks to the organisations who gave us permission to use their images for this exhibition: the Ashmolean Museum; National Portrait Gallery, London; the Non-Professional Archaeological Photographs (NPAPH) Project; the Palestine Exploration Fund, London; the Image Database at the University Library of Tuebingen; the Taylor and Francis Group.

All photos of the Oriental Museum collection were taken by the Exhibition Photography Team: Matthew Buick, Kim Devereux-West, Shona Holden and Jaime Witham.

Exhibition Content Lead: Jaime Witham; Exhibition Graphics/Design Lead: Isabel Clanfield; Photography Team Lead: Matthew Buick.