Meet Cuthbert Tunstall

Cuthbert Tunstall (1474 – 1559) was one of the most important, respected and controversial figures in Tudor England.

You may not recognise his name, but look closely and you will find it in the address book of kings and queens, scholars and diplomats, heroes and traitors.

Cuthbert served as Prince Bishop of Durham from 1530 to 1559 and lived through a period of political scandal and religious chaos that saw huge changes in England.

At times, Cuthbert held power and influence over the Tudor monarchs and important historic events.

At others, he faced imprisonment and came close to death.

Despite these challenges, Cuthbert used compromise, persuasion, a shrewd sense for danger and a little bit of luck to survive and thrive in one of the most turbulent periods of British history.

So, where did it all begin?

Cuthbert was born in Hackforth, North Yorkshire. He was the son of a northern knight called Sir Thomas Tunstall.

The family coat of arms can be seen in the courtyard of Durham Castle.

The three combs on the crest represent a family ancestor who was the barber of William the Conqueror.

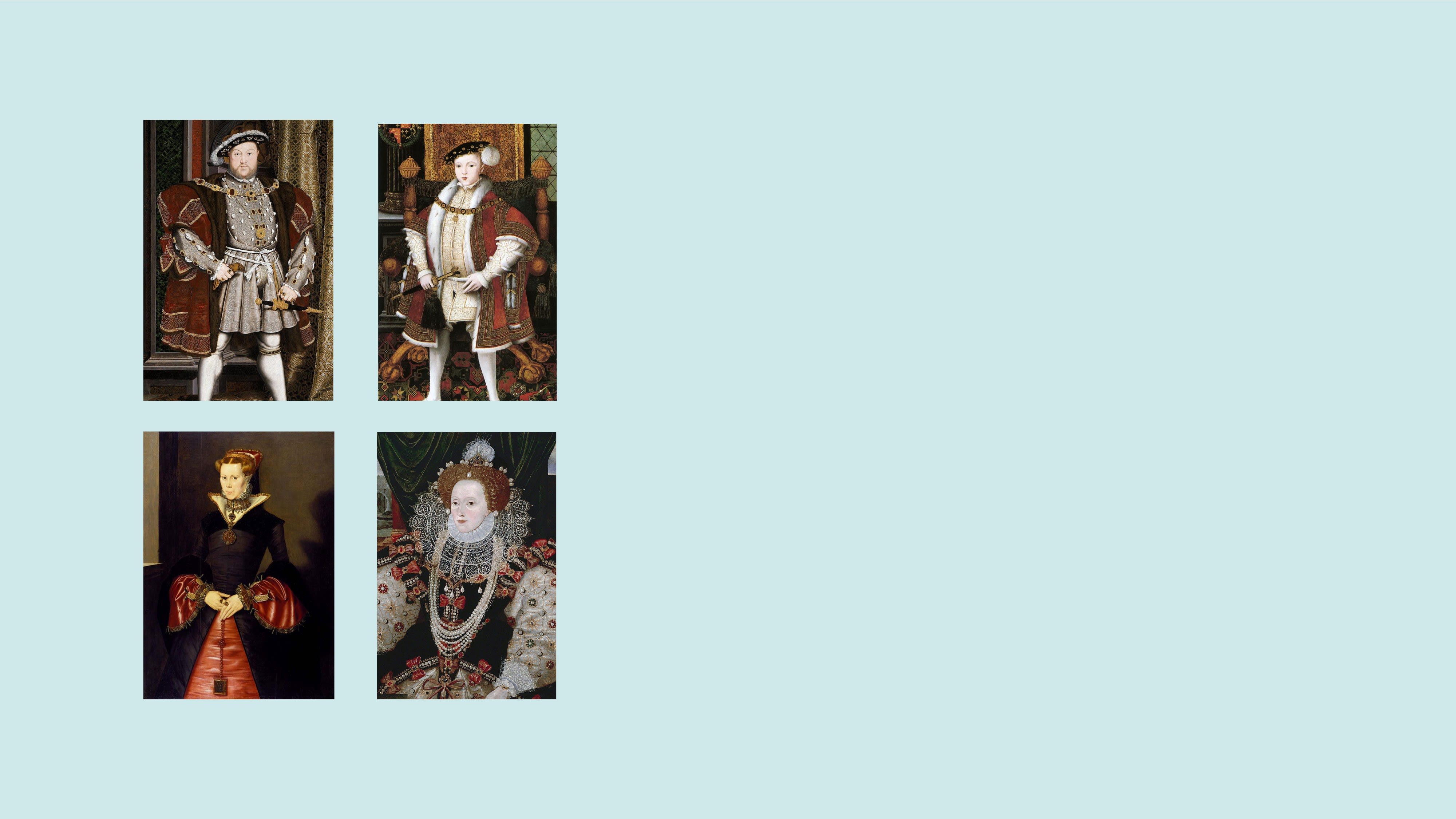

Cuthbert was bright and curious from a young age, attending the universities of Oxford and Cambridge before studying law at Padua

He built a reputation for his intellect and entered the Catholic Church when he returned to England.

Cuthbert was born in Hackforth, North Yorkshire. He was the son of a northern knight called Sir Thomas Tunstall.

The family coat of arms can be seen in the courtyard of Durham Castle.

The three combs on the crest represent a family ancestor who was the barber of William the Conqueror.

Cuthbert was bright and curious from a young age, attending the universities of Oxford and Cambridge before studying law at Padua

He built a reputation for his intellect and entered the Catholic Church when he returned to England.

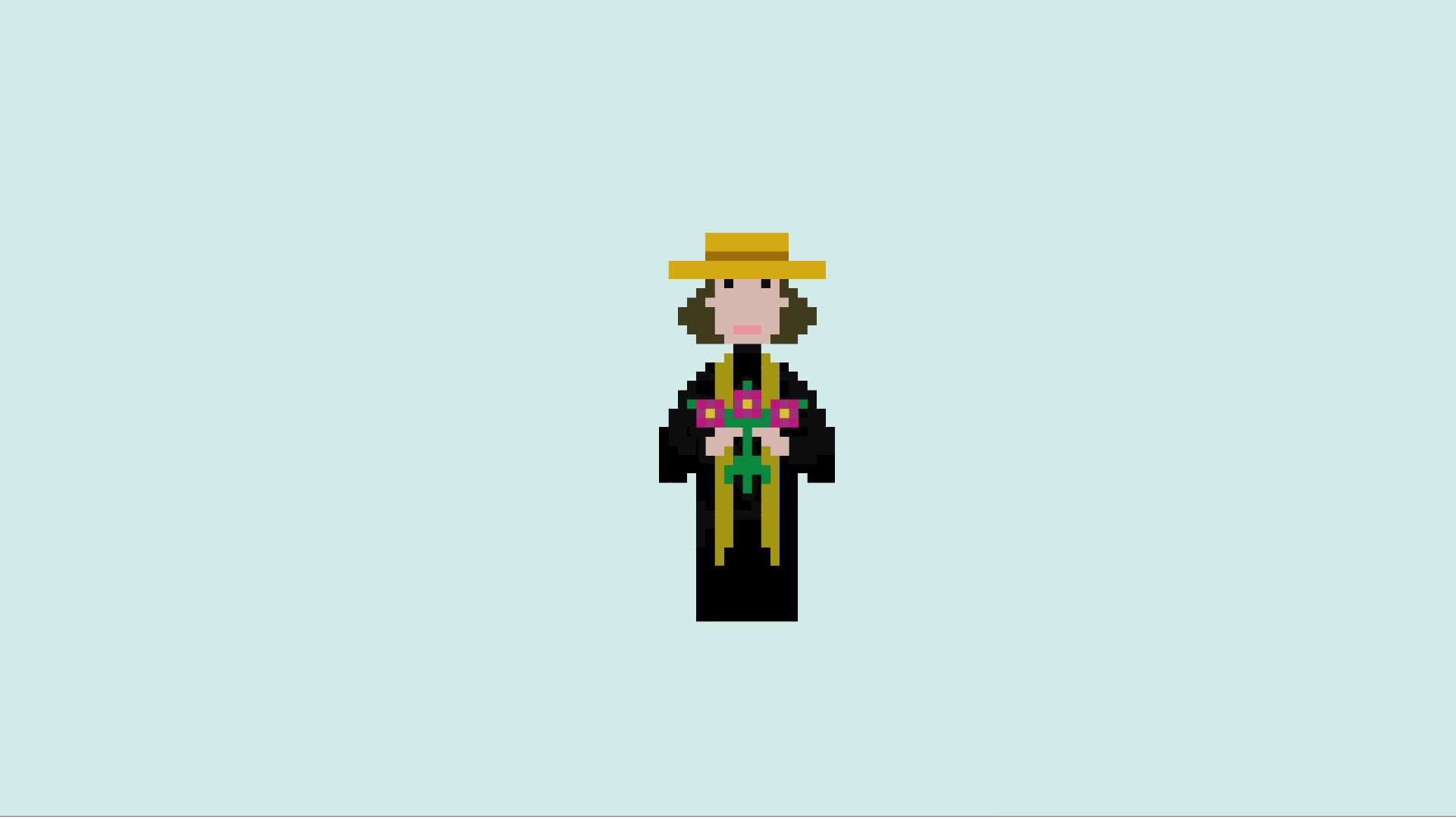

Throughout the Tudor period, a succession of strong-willed monarchs and nobles brought vastly different ideas, creating a dangerous environment for high-profile figures.

Many people in similar roles to Cuthbert were killed or forced to flee the country.

Surviving to see the reign of each of the Tudor monarchs is one of Cuthbert’s most impressive achievements, showing how clever, compromising and respected he was.

Henry VIII was King of England from 1509 to 1547.

Cuthbert and Henry had a complicated relationship. At times, Cuthbert felt the benefits of being close to the king, earning favours and rewards.

Silver Groat from 1526 - 29 showing King Henry VIII. Durham University Collections.

In return, he was expected to show loyalty and carry out orders.

Henry sent Cuthbert on several trips to Europe, allowing him to use his intelligence and diplomatic skills to negotiate peace and trade agreements.

The objects in the gallery below explore some of the links between Cuthbert and Henry.

Silver Groat from 1526 - 29 showing King Henry VIII. Durham University Collections.

Silver Groat from 1526 - 29 showing King Henry VIII. Durham University Collections.

The Parliament of Henry VIII, 1523 | This image shows a moment not long after Henry had named Cuthbert as Bishop of London. Cuthbert stands in a prominent position at the king’s right hand, behind the man dressed in red.

The Parliament of Henry VIII, 1523 | This image shows a moment not long after Henry had named Cuthbert as Bishop of London. Cuthbert stands in a prominent position at the king’s right hand, behind the man dressed in red.

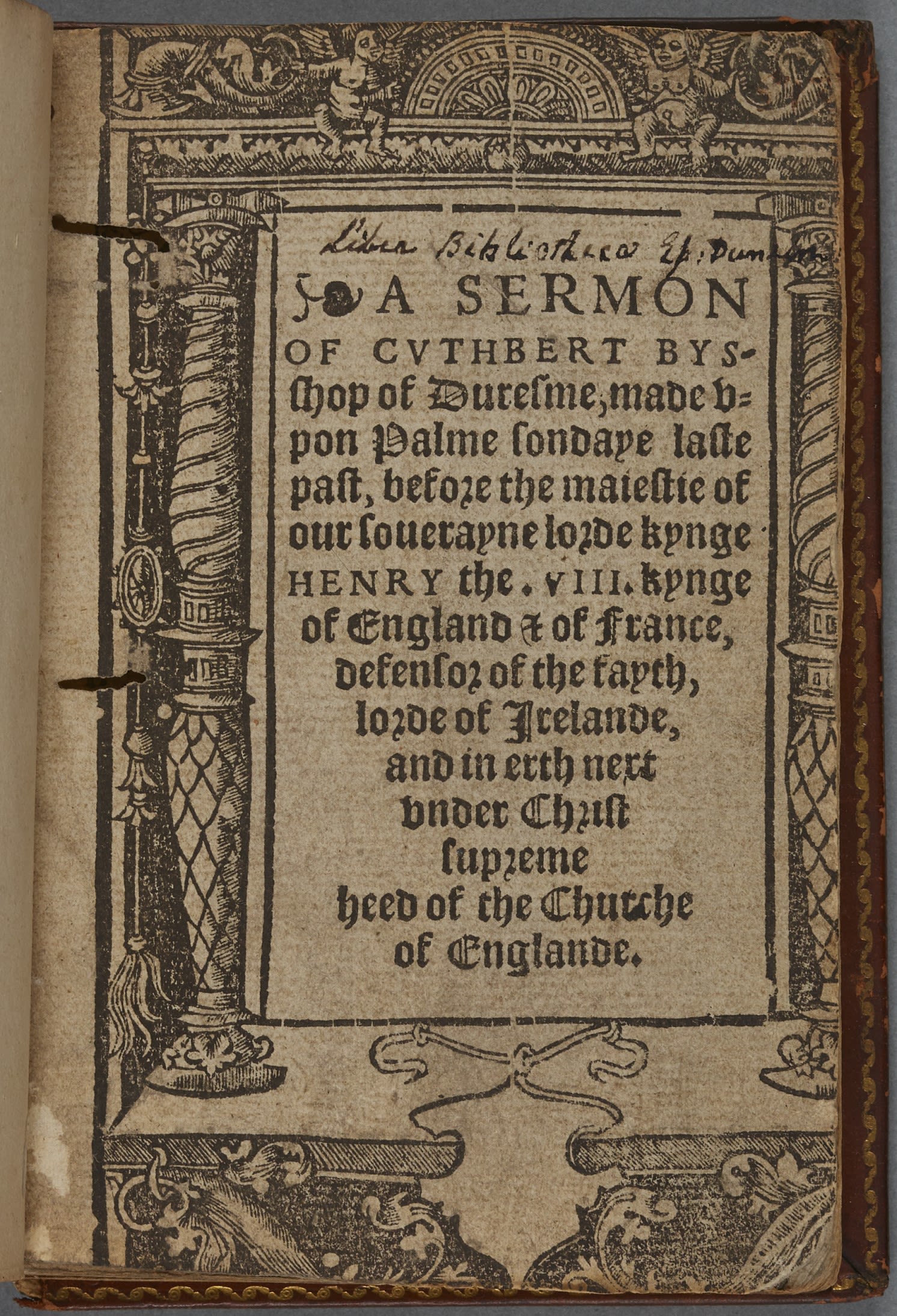

Cuthbert’s Palm Sunday Sermon for Henry VIII, 1539 | This sermon was delivered at a time when Cuthbert was trying to get closer to Henry VIII and influence his religious reforms. Durham University Library, SB 2087.

Cuthbert’s Palm Sunday Sermon for Henry VIII, 1539 | This sermon was delivered at a time when Cuthbert was trying to get closer to Henry VIII and influence his religious reforms. Durham University Library, SB 2087.

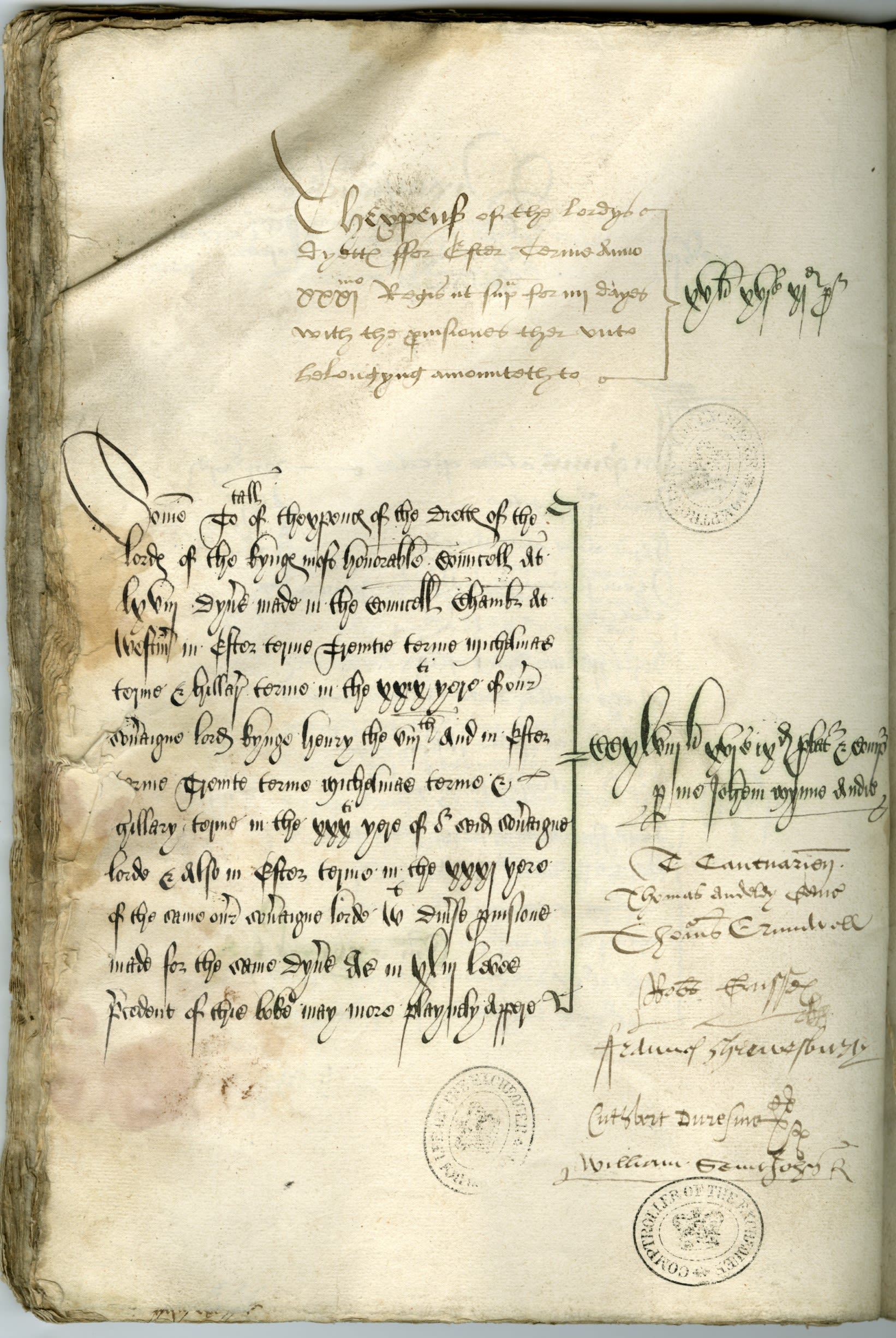

King’s Council Food Bill, 1540 | This document details the food and drink bill of one of the King's Councils that Cuthbert served. His signature 'Cuthbert Dunelm' is second from the bottom on the right hand side. The £250 spent by the group was more than 20 years of wages for a skilled tradesman at the time. The National Archives.

King’s Council Food Bill, 1540 | This document details the food and drink bill of one of the King's Councils that Cuthbert served. His signature 'Cuthbert Dunelm' is second from the bottom on the right hand side. The £250 spent by the group was more than 20 years of wages for a skilled tradesman at the time. The National Archives.

Cuthbert’s relationship with Henry was tested when the King decided to break from the Roman Catholic Church and establish the Church of England in the 1530s.

One of the main debates was whether or not Henry could divorce his wife and remarry.

Cuthbert eventually chose to support Henry, but only after his homes were searched for suspicious materials and some of his friends were executed.

Click to find out more about Thomas Cromwell and Catherine of Aragon

After calculating his options, Cuthbert decided it was better to stay alive and try to influence Henry, rather than becoming a martyr for his religion.

What would you do in Cuthbert's shoes?

Cuthbert’s relationship with Henry was tested when the King decided to break from the Roman Catholic Church and establish the Church of England in the 1530s.

One of the main debates was whether or not Henry could divorce his wife and remarry.

Cuthbert eventually chose to support Henry, but only after his homes were searched for suspicious materials and some of his friends were executed.

Click to find out more about Thomas Cromwell and Catherine of Aragon

After calculating his options, Cuthbert decided it was better to stay alive and try to influence Henry, rather than becoming a martyr for his religion.

What would you do in Cuthbert's shoes?

This chest was part of the furniture at Durham Castle during Cuthbert's time as prince bishop.

Castle legend has it that the body of Saint Cuthbert was hidden in the chest when Henry VIII’s men came to Durham Cathedral in the 1530s.

We don’t think this is true, but we do know that Cuthbert’s homes were searched for suspicious materials at the same time. Cuthbert was warned about the upcoming inspections and no incriminating evidence was found.

Perhaps the calculating bishop used chests like this as his hiding places.

When Henry died in 1547, Cuthbert was in a strong position as Prince Bishop of Durham.

Scroll down to find out about his relationship with the next two Tudor monarchs.

Click to find out more about Edward VI and Mary I

When Henry died in 1547, Cuthbert was in a strong position as Prince Bishop of Durham.

Scroll down to find out about his relationship with the next two Tudor monarchs.

Click to find out more about Edward VI and Mary I

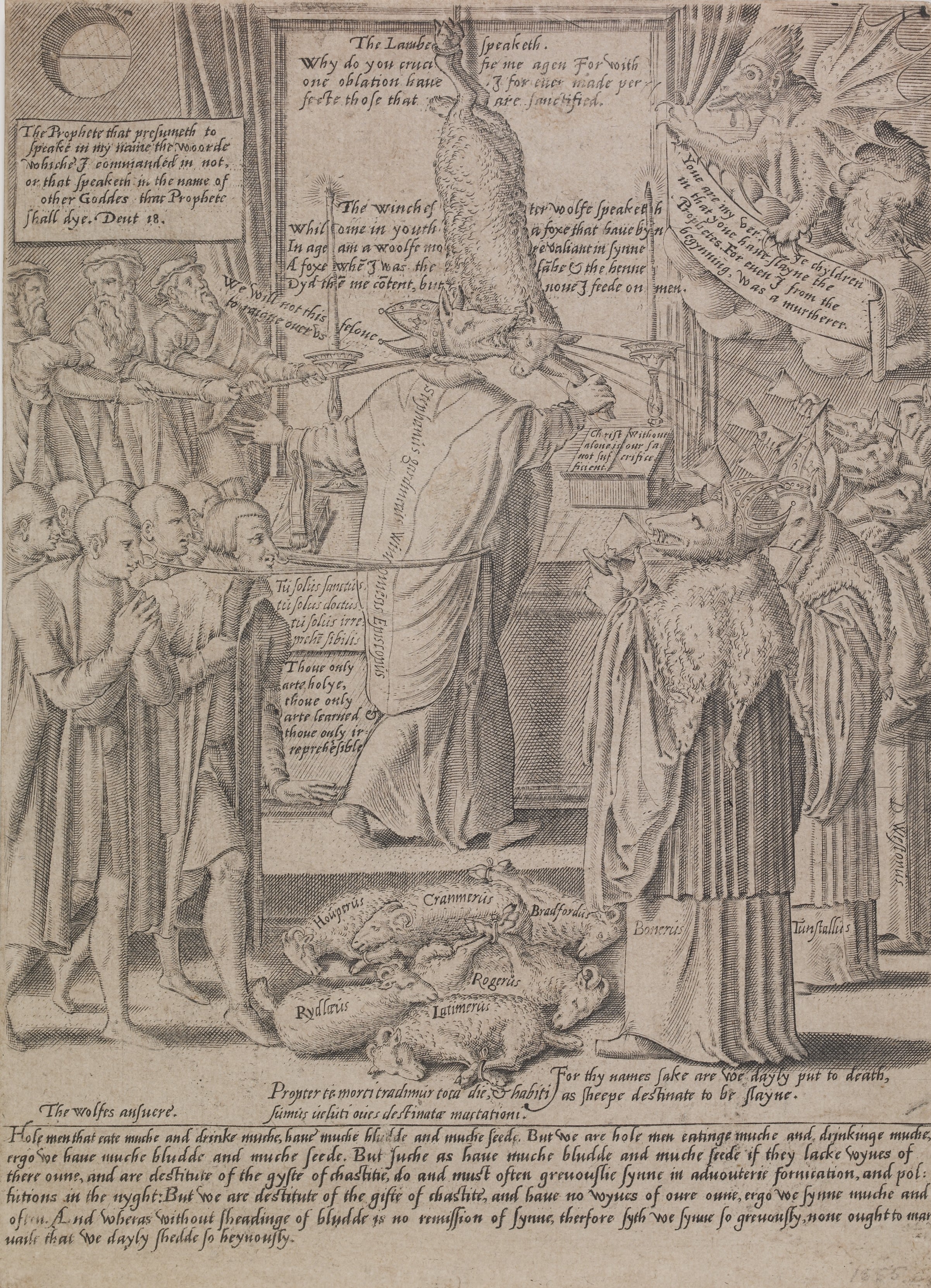

As a strict Catholic, Mary I set out to punish Protestants, including widespread executions.

This image, produced during Mary’s reign, depicts Cuthbert and other Catholic bishops as bloodthirsty wolves.

The slaughtered lambs represent the Protestants the queen had put to death.

In reality, Cuthbert was unlike most other bishops of his time. He studied all sides of the religious debate and used this knowledge to understand the views of others.

Throughout his time as a bishop in London and then Durham, Cuthbert never sentenced anyone to death for their religious views.

Instead he used debate, reason and compassion to try and persuade people to see his perspective.

As a strict Catholic, Mary I set out to punish Protestants, including widespread executions.

This image, produced during Mary’s reign, depicts Cuthbert and other Catholic bishops as bloodthirsty wolves.

The slaughtered lambs represent the Protestants the queen had put to death.

In reality, Cuthbert was unlike most other bishops of his time. He studied all sides of the religious debate and used this knowledge to understand the views of others.

Throughout his time as a bishop in London and then Durham, Cuthbert never sentenced anyone to death for their religious views.

Instead he used debate, reason and compassion to try and persuade people to see his perspective.

Mary’s reign lasted five years before Elizabeth I became Queen in 1558. By this time, Cuthbert was the longest serving and most respected bishop in England.

Although Elizabeth was keen to move the country away from Catholicism once again, the new queen was still eager to have Cuthbert’s support.

Silver Sixpence showing Queen Elizabeth I. Durham University Collections.

Silver Sixpence showing Queen Elizabeth I. Durham University Collections.

Cuthbert travelled to London for a private meeting with Elizabeth.

We don’t know for sure what they discussed, but the outcome saw Cuthbert placed under house arrest at Lambeth Palace after refusing to accept the queen’s reforms.

He spent his last days debating with Elizabeth’s advisors before dying in November 1559, aged 85.

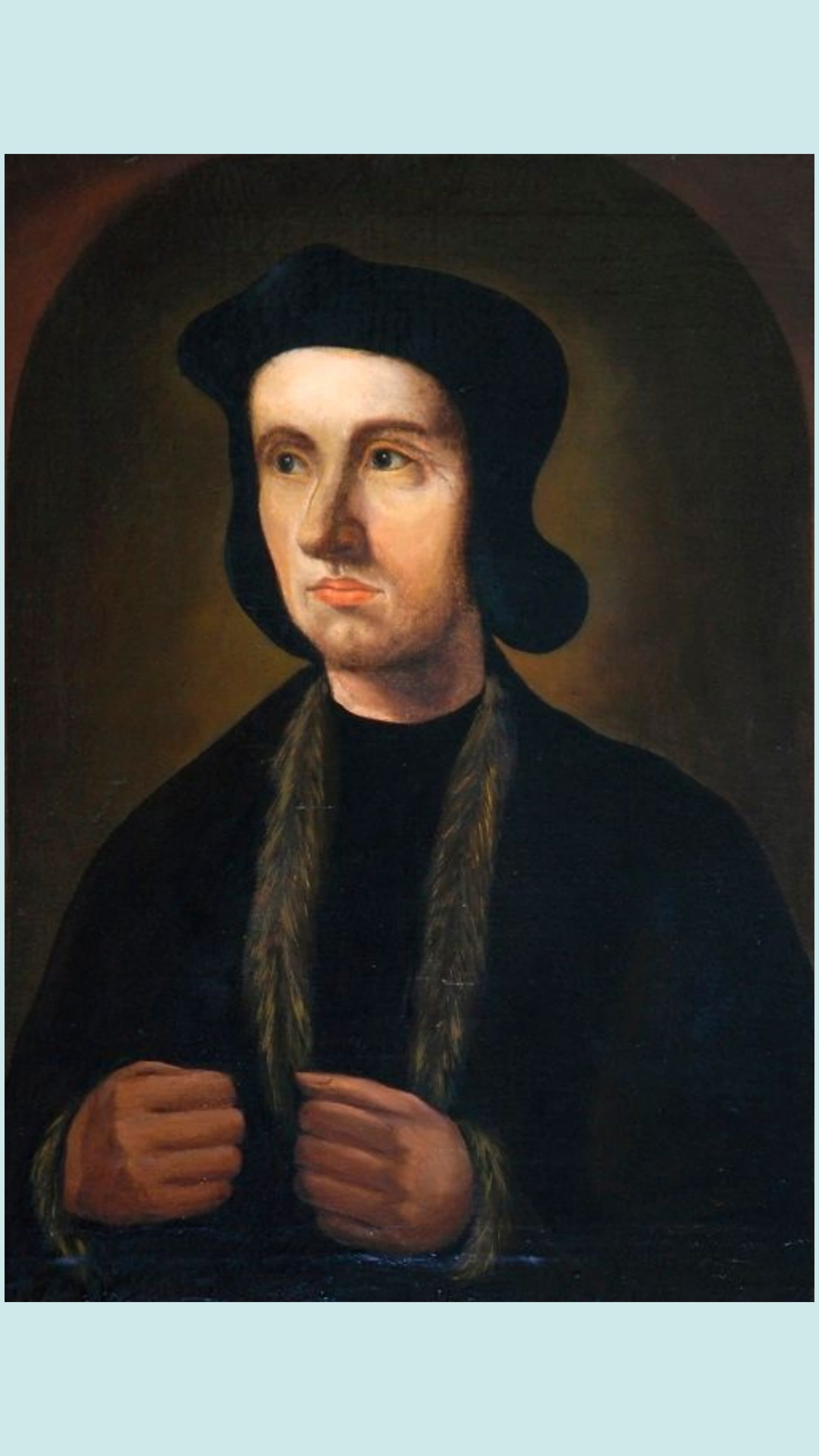

Portrait of Cuthbert from late in his life. © Bernard Terlay / Musée Granet, Ville d'Aix-en-Provence

Portrait of Cuthbert from late in his life. © Bernard Terlay / Musée Granet, Ville d'Aix-en-Provence

Many of the twists and turns in Cuthbert’s career were linked to his Catholic beliefs.

When Cuthbert took up his first roles in the Catholic Church in 1505, a religious career offered opportunities to travel, meet interesting people and earn a good living. This was perfect for an ambitious young man like Cuthbert.

Cuthbert’s diplomatic duties took him to Flanders and Germany where he made many new friends and allies.

He was rewarded for his work with the prestigious position of Bishop of London in 1522.

The objects in the gallery below explore some of the challenges that he faced in this new role.

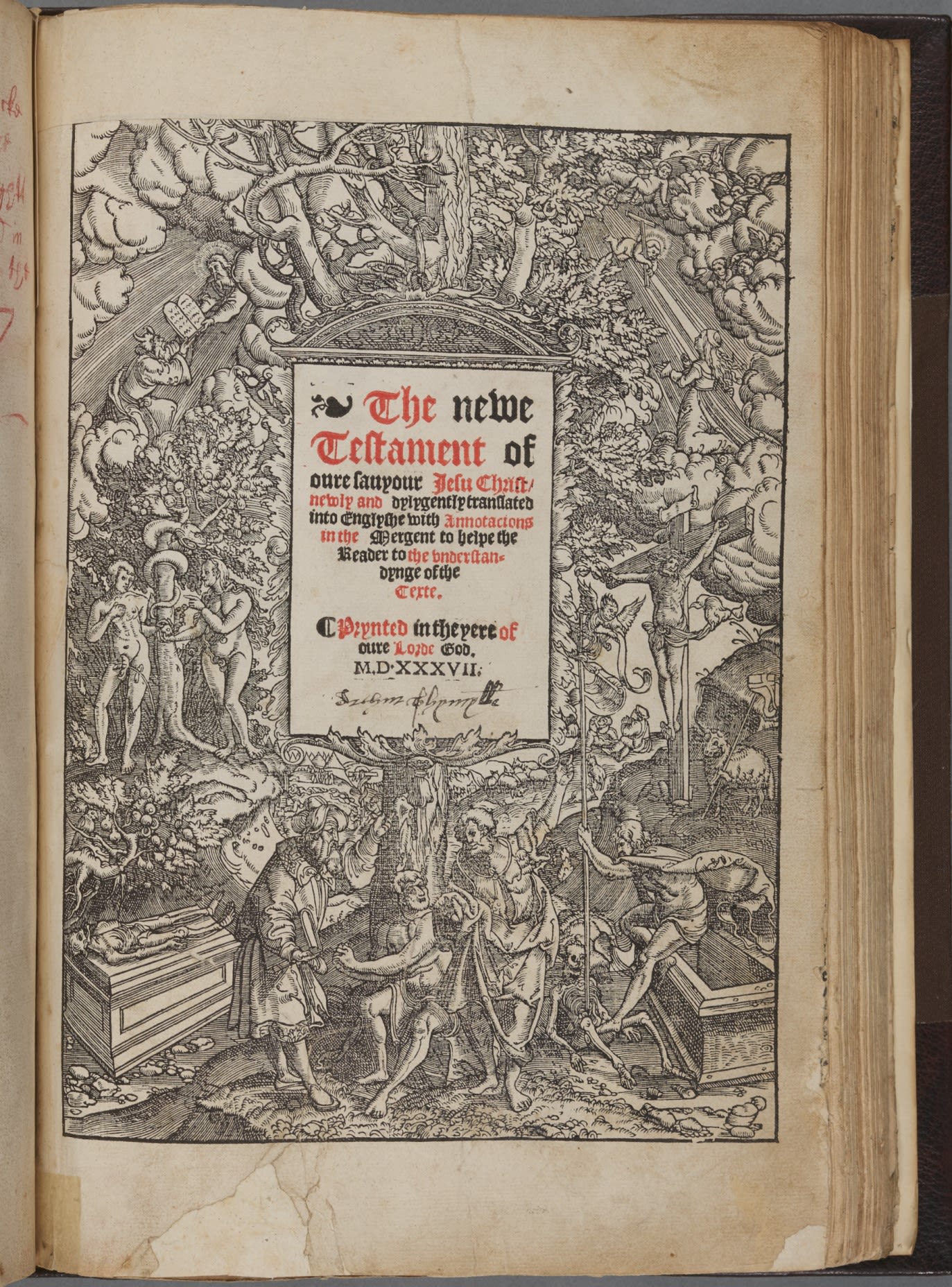

English Bible | This version of the New Testament, translated into English, was a major source of controversy during Cuthbert’s time as Bishop of London. Cuthbert called the work “naughtily translated” and feared the language used would affect how people understood the word of God. Durham University Library, SB+ 0101.

English Bible | This version of the New Testament, translated into English, was a major source of controversy during Cuthbert’s time as Bishop of London. Cuthbert called the work “naughtily translated” and feared the language used would affect how people understood the word of God. Durham University Library, SB+ 0101.

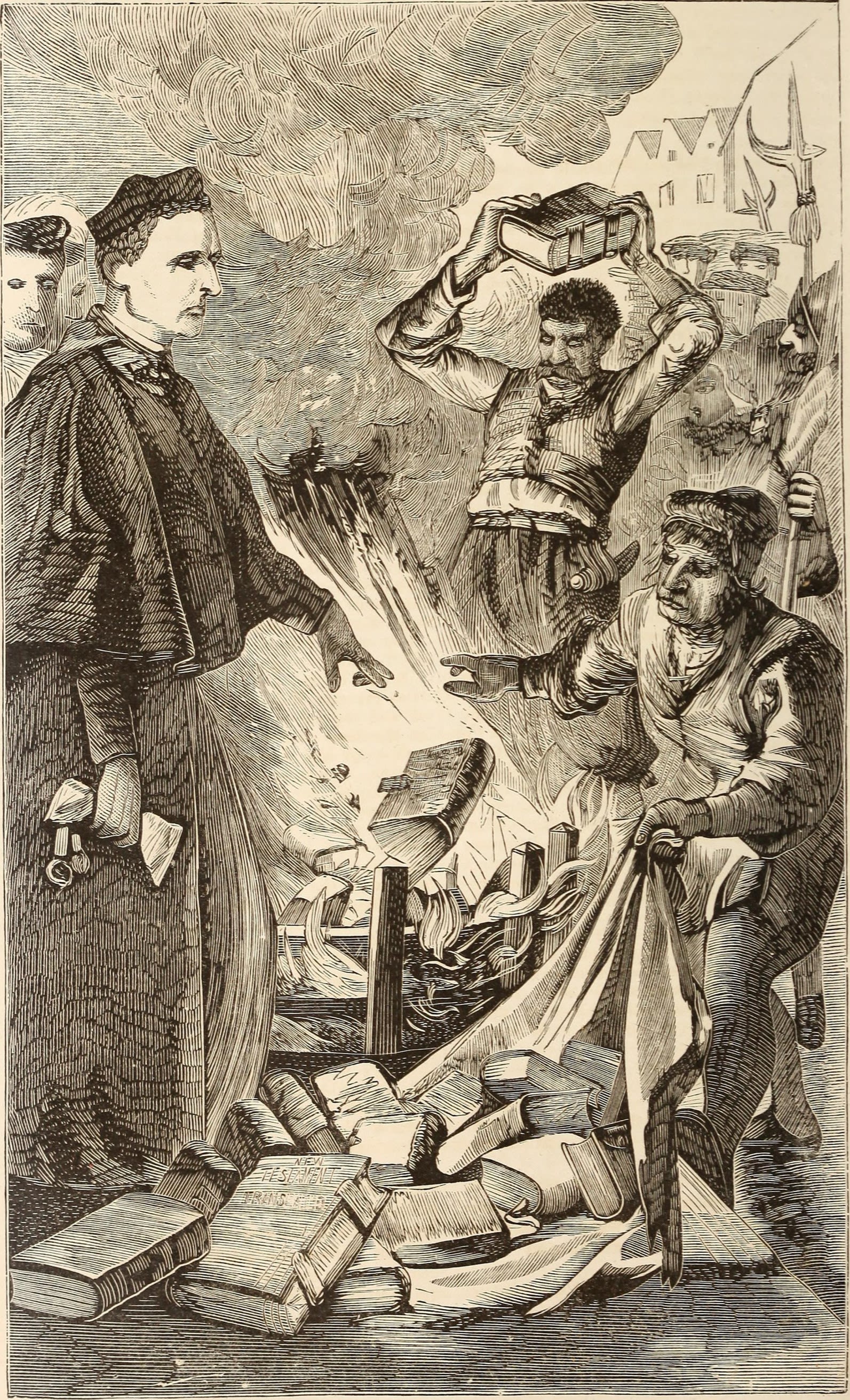

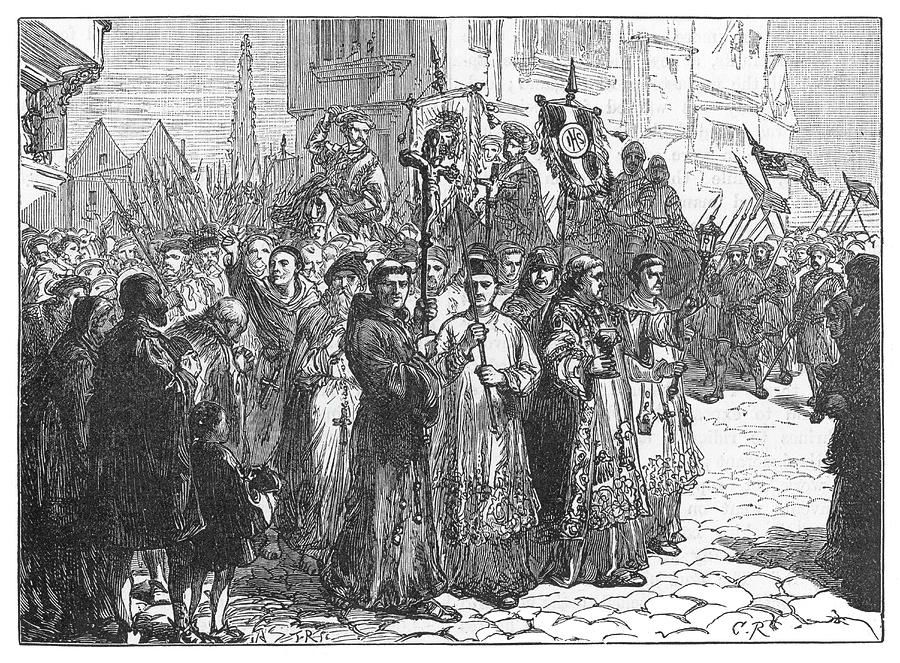

In 1526, Cuthbert ordered all copies of the book to be rounded up and burnt, as shown in this image. The author, William Tyndale, called Cuthbert a “ducking hypocrite” for his response. Today, burning books is seen as an extreme act of censorship. In Cuthbert’s time, he faced the stark choice of either burning the book or burning the people who owned and read it. Cuthbert favoured the more compassionate approach.

In 1526, Cuthbert ordered all copies of the book to be rounded up and burnt, as shown in this image. The author, William Tyndale, called Cuthbert a “ducking hypocrite” for his response. Today, burning books is seen as an extreme act of censorship. In Cuthbert’s time, he faced the stark choice of either burning the book or burning the people who owned and read it. Cuthbert favoured the more compassionate approach.

What would you do in Cuthbert's shoes?

Life in the church was exciting, but also dangerous.

Cuthbert was a high-profile Catholic at a time when Europe was being rocked by radical new religious ideas.

When Henry VIII officially broke with the Catholic Church, and the later Tudor monarchs brutally enforced their own religious views, Cuthbert used his brain, his wits and his powers of persuasion as he calculated the best way to survive.

One technique Cuthbert used to survive was persuading his friends to challenge his religious opponents.

Click to find out more about Martin Luther

Using extracts from letters sent between 1517 and 1530, the video below shows Cuthbert and Erasmus of Rotterdam sharing stories and gossip while hatching a plan to derail Martin Luther’s religious reforms.

What would you do in Cuthbert's shoes?

Life in the church was exciting, but also dangerous.

Cuthbert was a high-profile Catholic at a time when Europe was being rocked by radical new religious ideas.

When Henry VIII officially broke with the Catholic Church, and the later Tudor monarchs brutally enforced their own religious views, Cuthbert used his brain, his wits and his powers of persuasion as he calculated the best way to survive.

One technique Cuthbert used to survive was persuading his friends to challenge his religious opponents.

Click to find out more about Martin Luther

Using extracts from letters sent between 1517 and 1530, the video below shows Cuthbert and Erasmus of Rotterdam sharing stories and gossip while hatching a plan to derail Martin Luther’s religious reforms.

Click to play

Click to play

Some think Cuthbert survived by hiding from responsibility and abandoning his faith.

Others view him as a master of compromise, clever enough to see the value in refining his views over time.

The two paintings shown here can help us understand Cuthbert’s religious views and how he chose to present them.

The first painting, from the collection at Auckland Castle, shows him holding his rosary beads.

This is a visible symbol of Catholic prayer.

Painting shown courtesy of The Auckland Project and The Church Commissioners

In the second painting, from the collection at Durham Castle, Cuthbert’s pose is the same, but the rosary beads are missing.

It is believed that the painting was altered at some point to remove the rosary beads.

The portrait was analysed using X-ray fluorescence by the team at Durham University’s Department of Archaeology.

The varnish around the hands appears very wavy, suggesting that this area may have been reworked.

Cuthbert survived this unstable period thanks to his ability to compromise in public, but still privately hold his true beliefs.

The highest honour of Cuthbert’s religious career came when Henry made him Prince Bishop of Durham in 1530.

The next section of the exhibition explores Cuthbert’s local links.

The position of prince bishop was unique to Durham and gave Cuthbert special powers and privileges.

He could mint his own coins, try legal cases and raise taxes. He also gained substantial land and local mines and properties, including Durham Castle.

Cuthbert’s building works at Durham Castle are a lasting part of his legacy. The Tunstall Gallery was completed in 1543 and the Tunstall Chapel was finished in 1547.

The gallery was a fashionable space for gatherings, games and debate.

Cuthbert walked this room enjoying time with his friends and thinking over the big ideas of his time.

The chapel was a space for Cuthbert to pray and to preach, helping him balance his faith with his many other responsibilities.

This is the earliest printed map of County Durham, showing the area Cuthbert was responsible for as prince bishop.

Christopher Saxton’s map, Dunelmensis episcopatus, 1576. Durham University Library, SD+ 00232

Durham City was at the heart of Cuthbert's role. He lived in Durham Castle and was involved in the management of Durham Cathedral.

Cuthbert also had a residence at Auckland Castle. He built a new gallery and gateway and finished the great window of the dining hall.

County Durham stretched as far north as the River Tyne. Cuthbert paid to repair the southern half of the Tyne Bridge three times during his reign.

Cuthbert’s work also took him further north to the Scottish border. At various points, he was called on as a peacekeeper, serving as President of the Council of the North on two occasions.

Cuthbert’s duties also took him further south. When Henry VIII visited Yorkshire in 1541, Cuthbert took the King on a walk through the hills near Ripon.

Cuthbert was a nature lover who enjoyed gardening and declared the scenery in North Yorkshire as one of the greatest sights he had seen in all his travels.

But Cuthbert wasn’t always popular with everyone...

In October 1536, the Pilgrimage of Grace saw thousands of protestors occupy Durham, furious at Henry VIII’s religious reforms. Durham Castle was under threat and Cuthbert’s residence at Auckland Castle was ransacked.

This was a difficult position for Cuthbert. He had some sympathy with the protestors but was facing pressure from the king to put down the rebellion.

His response was to flee to Norham Castle on the Scottish border, staying away for almost four months.

What would you do in Cuthbert's shoes?

Throughout his time as prince bishop, Cuthbert worked hard to improve the lives of people in Durham. He delivered regular church services, gave money to the poor and built a new public tollbooth with shops and stalls in Durham Market Place.

Education was also a priority for Cuthbert.

Cuthbert loved to surround himself with people who shared his interests and tested his intellect.

Use the interactive below to meet some of Cuthbert's scholarly circle of friends.

Cuthbert was convinced that a good education gave people the power to make positive changes in the world and wanted the people of Durham to have the same opportunities that he did.

Throughout his time as prince bishop, he took an active role in the funding and curriculum of Durham Grammar School, ensuring that young men would learn the Latin and Greek they needed to attend university.

He also developed the library at Durham Cathedral and protected its books when Henry VIII’s men carried out inspections.

Cuthbert loved to surround himself with people who shared his interests and tested his intellect.

Use the interactive below to meet some of Cuthbert's scholarly circle of friends.

Cuthbert was convinced that a good education gave people the power to make positive changes in the world and wanted the people of Durham to have the same opportunities that he did.

Throughout his time as prince bishop, he took an active role in the funding and curriculum of Durham Grammar School, ensuring that young men would learn the Latin and Greek they needed to attend university.

He also developed the library at Durham Cathedral and protected its books when Henry VIII’s men carried out inspections.

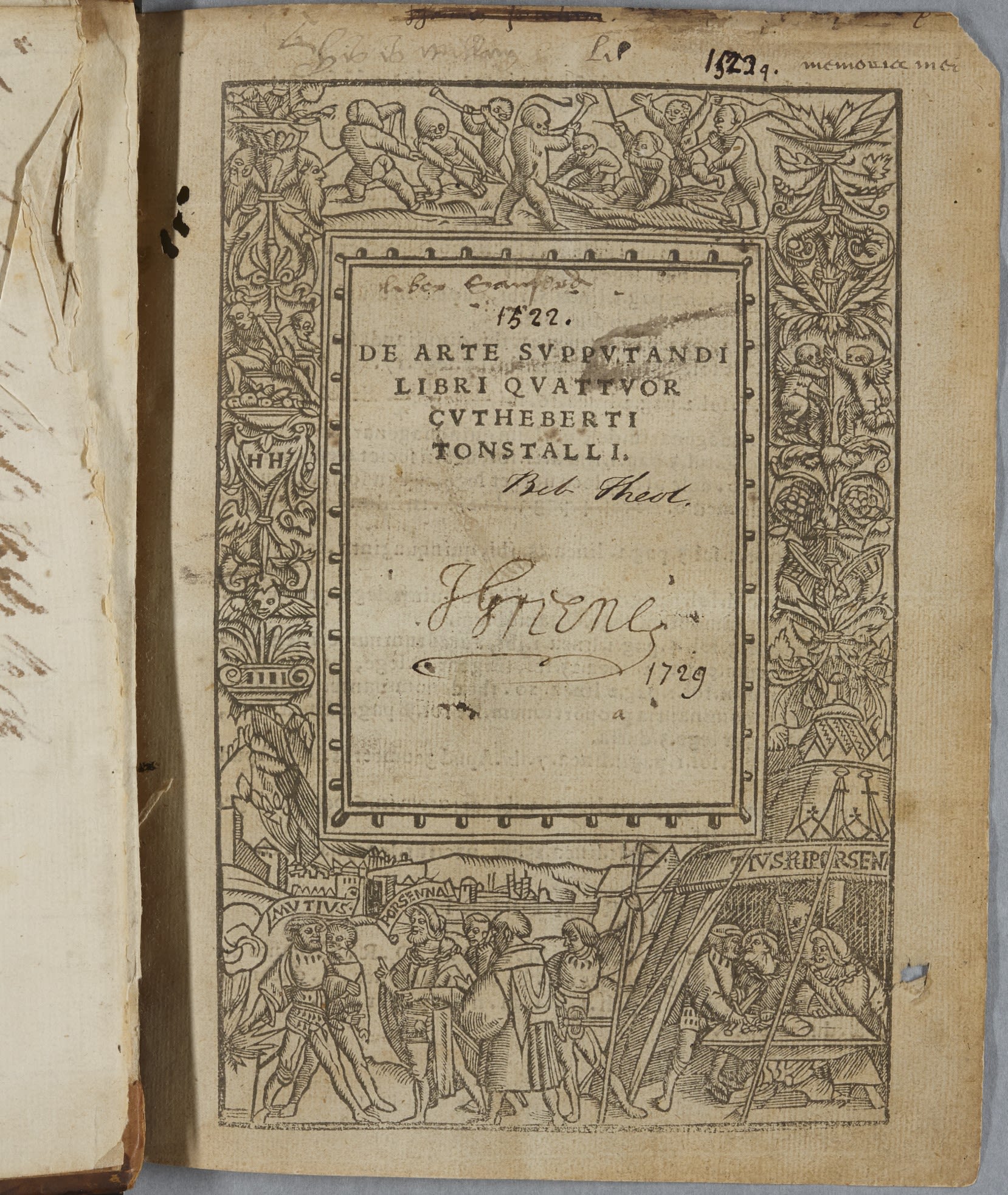

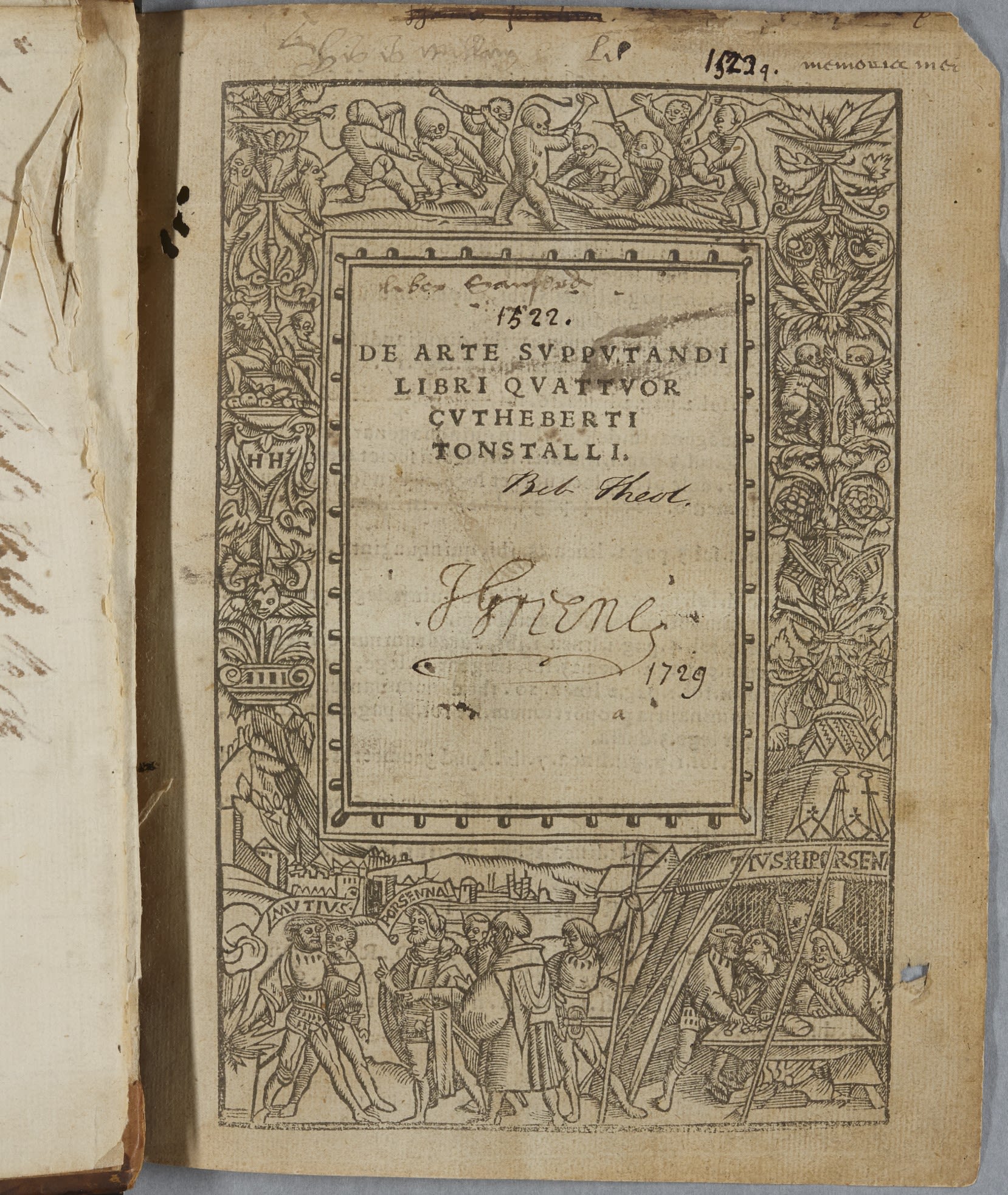

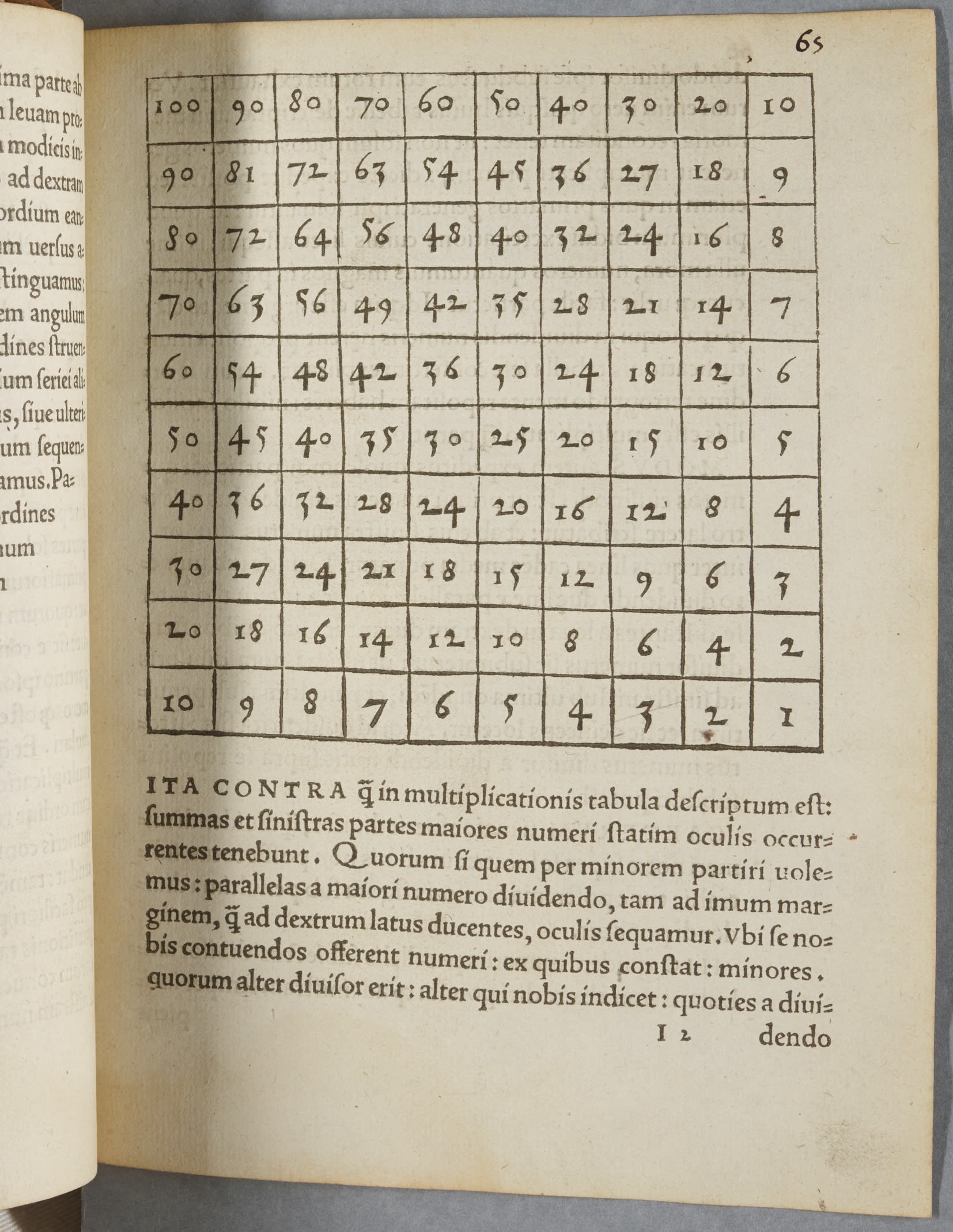

Cuthbert Tunstall, De arte supputandi, 1522 | This book is displayed with permission of the Trustees of Ushaw Historic House, Chapels & Gardens.

Cuthbert Tunstall, De arte supputandi, 1522 | This book is displayed with permission of the Trustees of Ushaw Historic House, Chapels & Gardens.

Cuthbert was ahead of his time by choosing to study mathematics.

Love it or hate it, maths is a key part of everyone’s general education. Today, most people take for granted the ability to count and do basic calculations. This was not the case in Cuthbert’s lifetime.

In the Tudor period, most wealthy and educated people used professional clerks for tasks involving maths and finance as they did not possess these skills themselves. Cuthbert himself had lost money after he was misled by a clerk and vowed that everyone should develop their own working knowledge of maths.

Cuthbert Tunstall, De arte supputandi, 1522 | This book is displayed with permission of the Trustees of Ushaw Historic House, Chapels & Gardens.

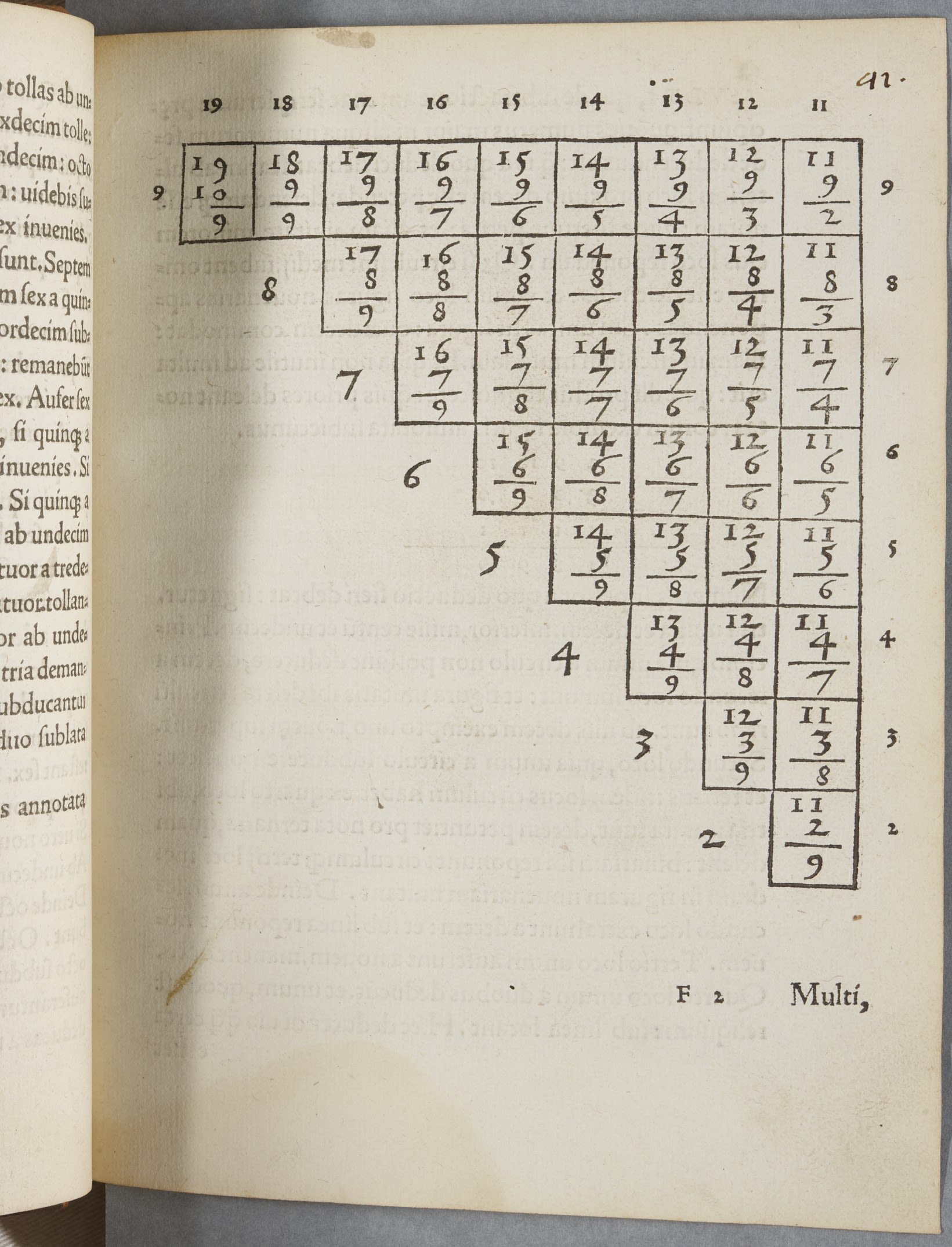

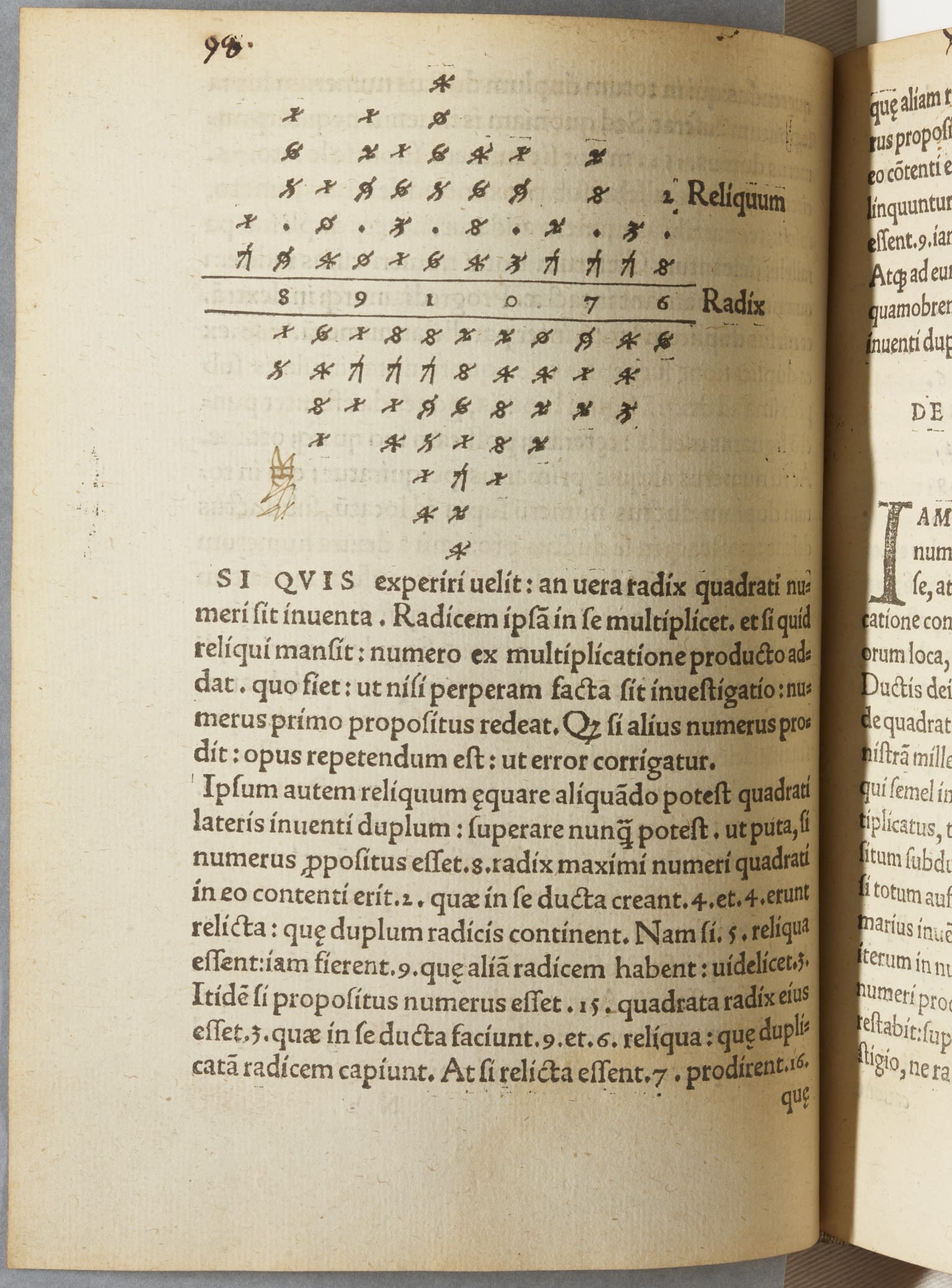

Cuthbert published De arte supputandi (On the art of counting) in 1522. This was the first maths book published in England and covers addition and subtraction, geometry, long division and the basics of accounting.

The multiplication table and method of subtraction shown here remain familiar. Some of the more complex elements of Tudor mathematics present a greater challenge to a contemporary audience!

The multiplication table and method of subtraction shown here remain familiar. Some of the more complex elements of Tudor mathematics present a greater challenge to a contemporary audience!

Cuthbert’s book was based on an earlier work by Luca Pacioli, maths tutor to Leonardo da Vinci.

Cuthbert’s book was based on an earlier work by Luca Pacioli, maths tutor to Leonardo da Vinci.

In the centuries that followed the publication of Cuthbert’s book, maths became increasingly fundamental to daily life and much more respected as a scholarly discipline.

In the centuries that followed the publication of Cuthbert’s book, maths became increasingly fundamental to daily life and much more respected as a scholarly discipline.

Although Cuthbert was famous, powerful and respected in his lifetime, today he is not as well-known as other major figures from the Tudor period.

He died quietly.

Not quite a hero, not quite a traitor.

Today he lives on through his writing, his building works in Durham and the many stories of his character and personality.

Cuthbert lived in polarised times, when the powerful were ruthless and brutally enforced their position. He not only survived this period, but emerged with a reputation for kindness, compassion and understanding.

Beyond his own religious views and intellectual interests, he respected the opinions of others and was optimistic about the human power for good.

Cuthbert Tunstall (1474 – 1559)

Scholar. Collector. Bishop. Diplomat. Gardener. Builder.

Your feedback is important to us. Please take a minute to complete our visitor survey.