When you think about the history of Durham, what comes to mind? Beautiful architecture, rich or powerful people, and facts you find in history books. But how often do we stop and think about the lives of ordinary people?

Archaeology can tell us so much about these lives and helps us discover fascinating stories from Durham’s history which we might never have known.

Objects found by archaeologists show us that people of the past are not so different from us today.

Their discoveries can help us understand the lives of everyday people, shedding light on stories which are often overlooked. They can reveal stories of individuals or places, and even show us a single celebratory moment in history.

This online exhibition delves deeper into the tales of the key objects presented in the exhibition at the Museum of Archaeology in Durham. The objects in this exhibition were found within the World Heritage Site or collected from the River Wear by underwater archaeologist, Gary Bankhead.

This exhibition was curated by MA Museum and Artefact Studies students from the Department of Archaeology, Durham University.

Stories of the Everyday

Durham has been a bustling centre of trade, religion, education and politics for the last thousand years. Alongside historic buildings and events, ordinary people lived and worked here.

These people made Durham what it was, but their lives and stories often go untold. Each object in this online exhibition can tell us about how people in the past lived and reveal a vibrant and busy local life. People’s experience of life through education, entertainment, work, play, food and fashion cannot always be preserved in writing.

All of these objects once belonged to someone. Whether they were regular household items or someone's most treasured possession, they are all important in shaping our understanding of the people of our past. Let us see what kind of stories they can tell...

Bronze Cauldron

1300s

This bronze cauldron found in New Elvet was used for ordinary, everyday cooking. Considering its size, it could have been owned by a family or shared in the community. To cook, the cauldron would have been suspended above an open fire or placed in the embers. How is this similar or different from the way we cook today?

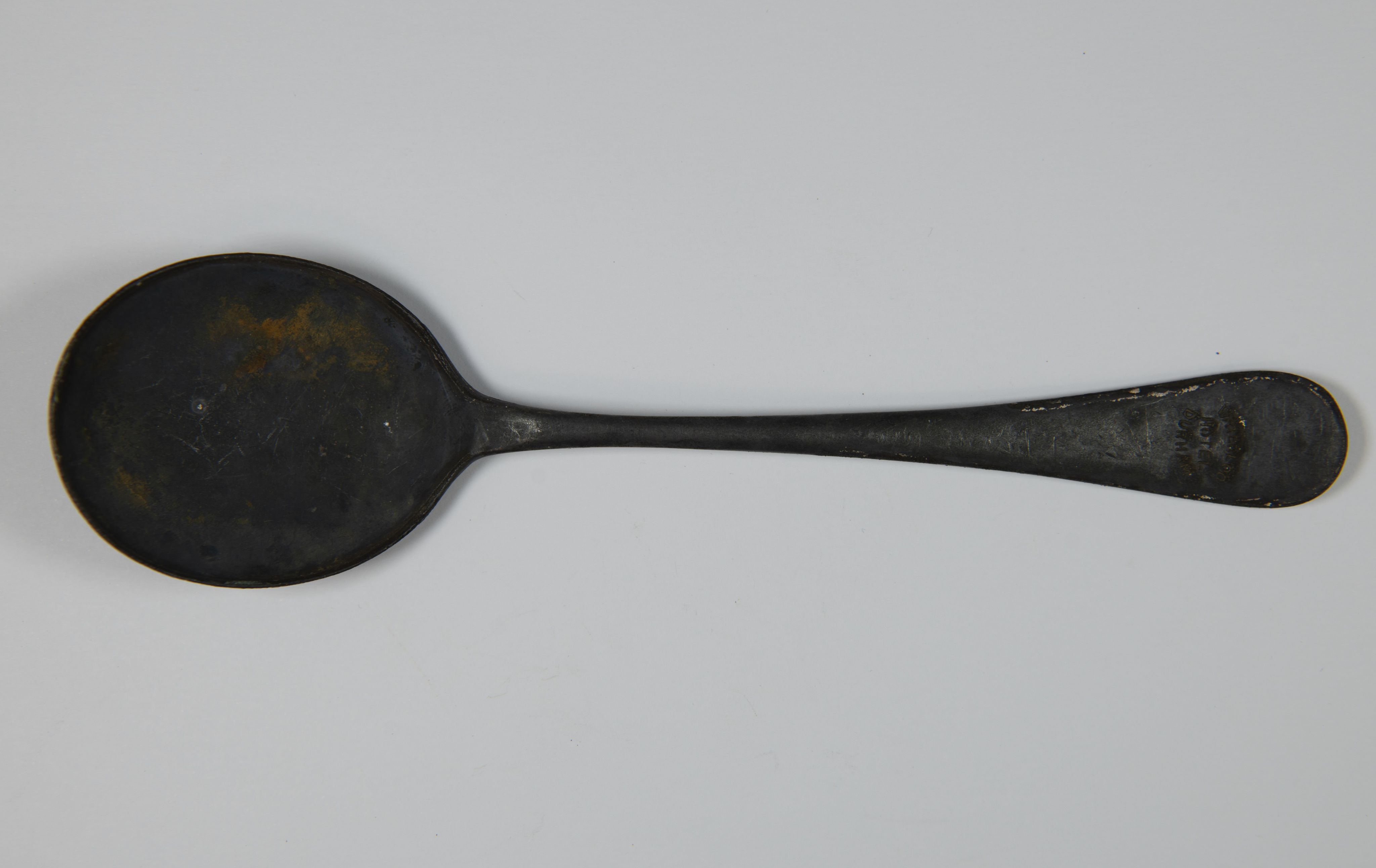

Waterloo Hotel Spoon

1900s

This spoon has ‘Waterloo Hotel Durham’ inscribed on it. The hotel was located at 61 Old Elvet. It was made by Walter and Hall, who were based in Sheffield.

Following the defeat of Napoleon’s French army at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, two hotels in Old Elvet changed their names to the Waterloo Hotel. One of them is still a hotel, which is now called ‘The Royal County’.

Dentures

1800s-1900s

These dentures are made of vulcanite and enamel. There is a gap on the left side, perhaps for an existing tooth. There is even a metal disc on the top, which is part of the suction mechanism which was used to help keep the dentures in place

Dentures were far more common prior to the introduction of the National Health Service; it is estimated that in 1968, the majority of over 65-year-olds possessed no natural teeth. At the beginning of the 20th century, the cost of dentures was the same as several months of wages for average working men. If dentures were expensive and valued, how did this set end up in the River Wear?

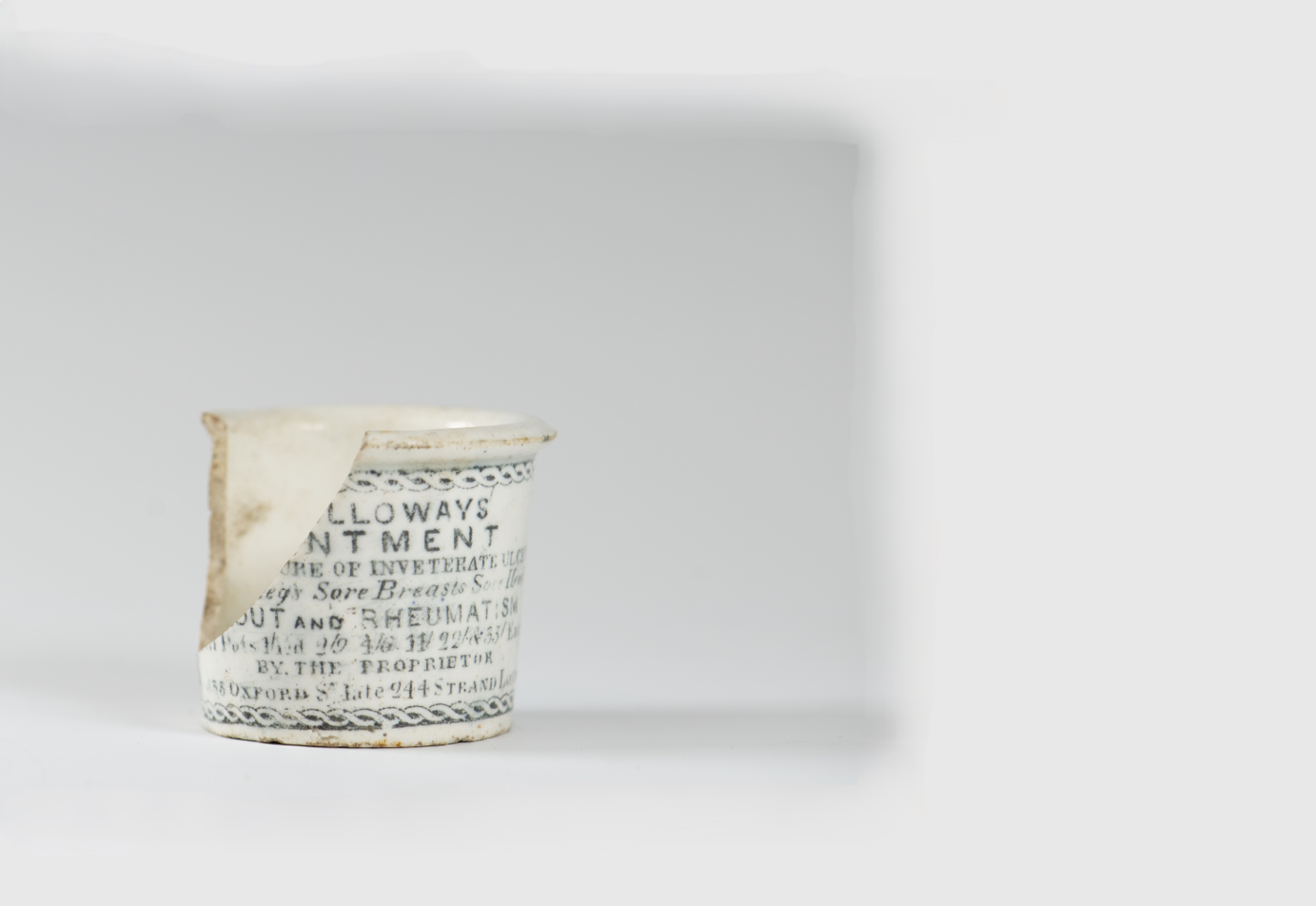

Ointment Jar

[1800s-1900s] 1840-1920

Holloway’s Ointment was successfully advertised as a Victorian cure for lots of different diseases like gout, ulcers, and headaches, despite no evidence that it worked.

The text on the front reads:

Holloways Ointment

For the Cure of Inverterate Ulcers

Bad Legs Sore Breasts Sore Hands

GOUT AND RHEUMATISM

Pots 1/1d 2/9 4/6 11/ 22/ & 33/ Each

By the Proprietor

533 Oxford St Late 244 Strand London

Holloway put a large amount of money into advertising, which made the company one of the best-known brands in England.

Lead Comb

1500s-1700s

During this period, strong single-sided combs were used to detangle hair, whereas thin double-sided combs were used for finding head lice (nits). In Europe, lead combs were sometimes used to dye lighter hair, a darker colour. This is because of the way lead interacts with the natural components in the hair. People dyed their hair to look younger, but lead combs can cause lead poisoning, which actually leads to hair loss and other health issues. A strand of red hair was found on this comb when it was recovered from the River Wear over 300 years later.

Watches

1800s-2000s

These watches could all be considered valuable to their owners, but not for the same reasons. Pocket watches like that on the bottom left were once a symbol of wealth, but from the late 19th to early 20th century, they became commonplace for everyone to wear.

The watch on the right looks like a Rolex. Rolex is an expensive luxury brand, but this one is a fake. The owner may have wanted to appear wealthy without having to pay the £5-45 thousand that the original watches cost.

The watch on the top left is a nurses watch. These watches were never meant to show wealth or statues. They were a symbol of achievement, often personalised and given as graduation gifts to nursing students.

If these watches were valuable to their owners, how did they end up in the River Wear?

Horseshoe Charm

1900s

The horseshoe is now a lucky charm to ward off evil. The origin of the horseshoe as good luck stems from a 10th century story about an English bishop named St. Dunstan. He was known as the patron saint of blacksmiths. When the Devil came to his door, he forced a horseshoe on the Devil’s cloven hoof very painfully. After this, the Devil agreed to never enter over a threshold with a horseshoe nailed above it. There are many different versions of this story told throughout Britain and Ireland. The horseshoe is now a lucky charm to ward off evil.

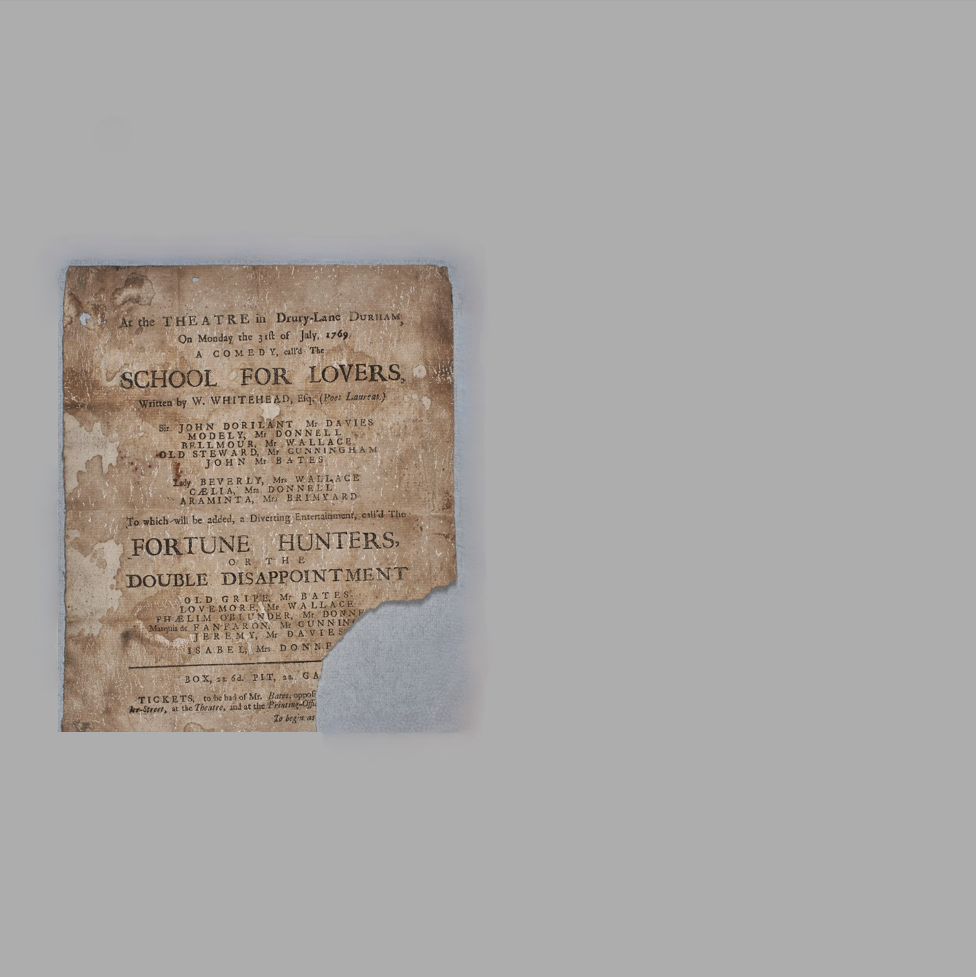

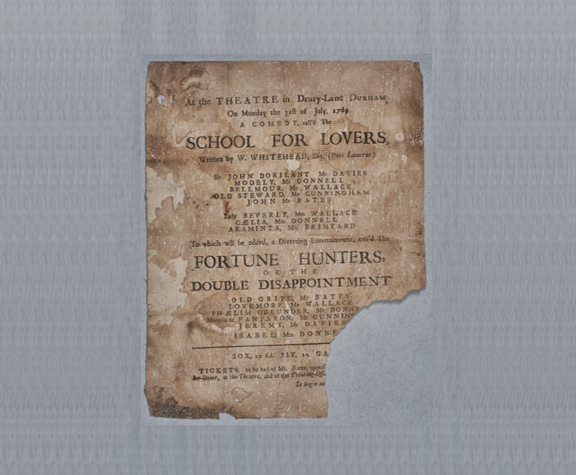

Playbill from Drury Lane Theatre

1769

Theatre was incredibly popular in Durham during the 17th and 18th century. This playbill has survived incredibly well and is advertising performances of plays called ‘The Two Lovers’ and ‘The Fortune Hunters’. These plays took place at Durham’s Drury Lane Theatre, which was down a narrow alleyway leading to the river from Saddler Street, and was named after the famous London attraction.

Stories of Celebration

From birthdays to coronations, and from marching bands to jubilees, we all have different ways of celebrating special occasions. These events have left their mark on Durham.

Through archaeological discoveries, we can uncover how residents of Durham celebrated personally and communally. They also reveal how people celebrated historically significant events of Durham like the appointment of a new mayor or the annual Durham Miner's Gala.

Durham was an important Medieval pilgrimage site, and pilgrims still journey here today to celebrate their faith. It is a place of religious importance to many people. Archaeologists have found evidence in the last 1000 years of these journeys to Durham.

Durham continues to commemorate special events and occasions. At certain times of the year, the city becomes a thriving hub of music, people, and sound. What brings you into the centre of Durham today?

Banner Belt Fitting

1900s

This belt fitting was found in the River Wear near Elvet Bridge. It would have been used to support the pole when carrying a banner. Miners Banners are carried in the procession that crosses Elvet Bridge during the annual Durham Miner’s Gala. Starting in 1871, this event is a celebration of the region’s miners.

Band of Hope Medallion

1900s

The Temperance Movement of the 19th Century encouraged people to not drink alcohol. It was aimed at both children and adults. Band of Hope medallions, first made in 1855, were handed out to people to celebrate and encourage sobriety.

Mayor Coin

1911

This coin depicts the Marquis and Marchioness of Londonderry, commemorated as Mayor and Mayoress of Durham. It is remarkable as it was found on 31st August 2011 by Gary Bankhead, exactly 100 years from the date it celebrated!

Pilgrim Badge and Pilgrim Pendant

1300s, 1900s

Both of these objects were found in the River Wear. They show the practice of throwing religious items into the river as offerings, done by two people born centuries apart. They are both St. Cuthbert's Cross, symbolising the saint of Durham and showing the continued importance of this city to the Christian faith.

Harmonica Reed Plate and Music Sheet Stand

1800s – 1900s

Harmonicas are wind instruments with two reed plates on each side, and one comb in the middle. The rest of this harmonica is missing, with only one reed plate found. Music sheet stands hold sheet music for musicians to read while playing their instruments. Perhaps both these objects were used by musicians on the bridges of Durham, just as street musicians continue to play on the same bridges today.

Stories of Individuals

Some objects can tell us more about what was happening in a place and reveal unique stories of individuals. This section contains objects that represent the stories and experiences of people across 400 years of history.

Some individuals leave a lot of objects and information about their lives behind, such as Arthur Beanlands and Ellen Caldcleugh, who both lived and worked in Durham in the 1800s. Some individuals may only be remembered as moments in time, captured through mementos such as rings, bracelets, and dog tags. Then there are the stories of the Scottish Soldiers who died imprisoned in Durham Cathedral and were in many ways robbed of their individual stories until rediscovered by archaeologists.

In this section, we can begin to uncover unique stories from many different people who lived in Durham.

Jewish Love Token

1900s

These types of tokens were exchanged between partners or friends during a long period of separation. Inscribed in Hebrew, the left heart reads ‘MIZPAH’, which can be interpreted as ‘watchtower’ or ‘May God Watch Over You’. The right heart is inscribed with a passage from the Bible: “The Lord Watch Between Thee and Me”.

‘Paul’ Knuckleduster

1900s

Knuckledusters, also known as brass knuckles, are a weapon designed to be worn around the knuckles in hand-to-hand fighting. They were criminalised in the 1980s. Perhaps this one was thrown away soon after, because the owner’s name was inscribed on it.

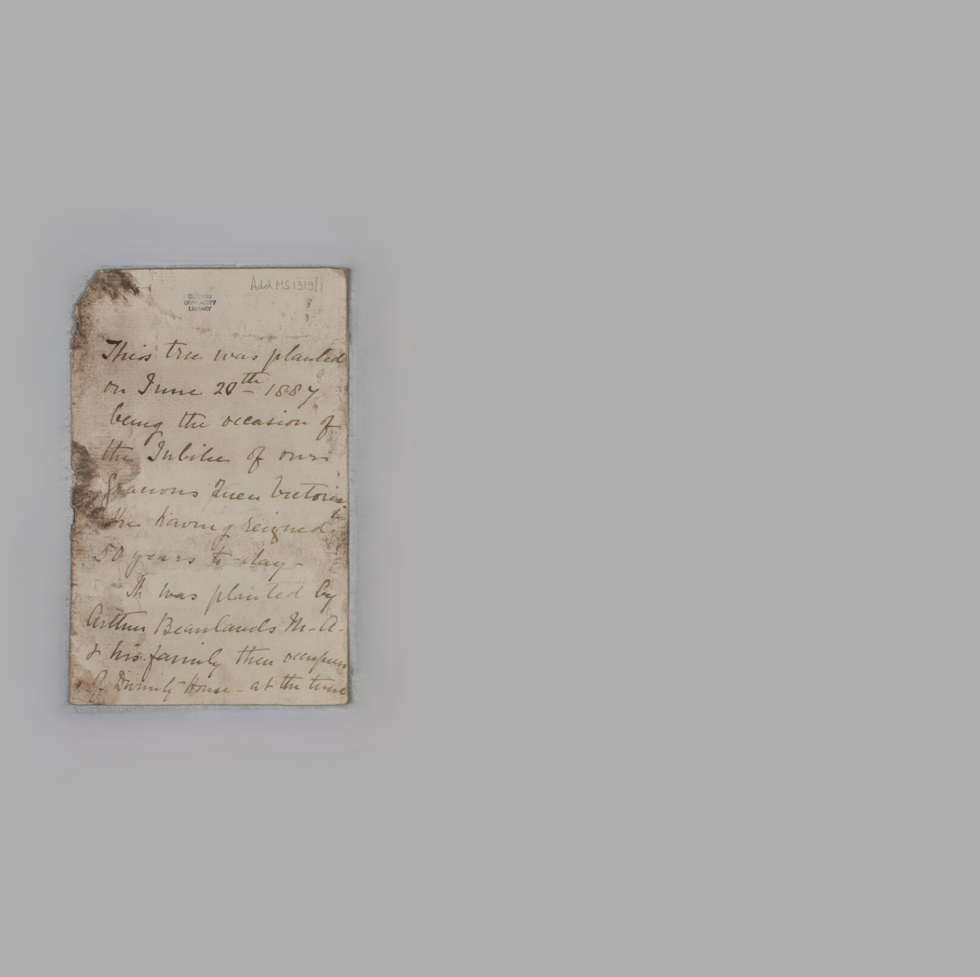

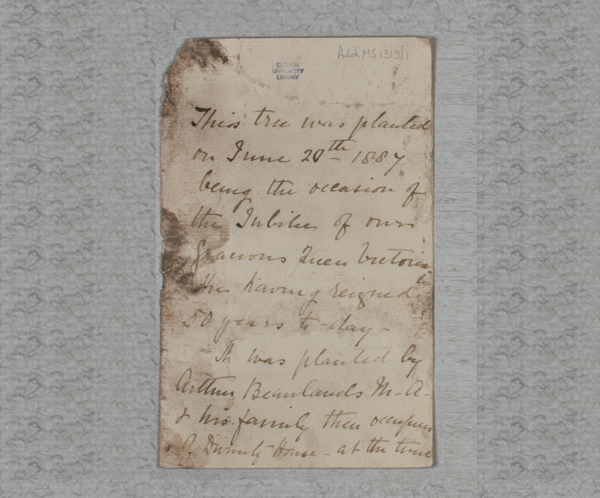

Divinity House Tree Note

1887

Arthur Beanlands wrote this note and planted a tree to commemorate the 50th Jubilee of Queen Victoria on 20 June 1887. The text of the note reads:

This tree was planted on

June 20th 1887 being the

occasion of the Jubilee of

our Gracious Queen Victoria,

She having reigned 50 years

to-day. It was planted by

Arthur Beanlands M.A. and

his family then occupiers of

Divinity House – at the time..

Arthur was one of the first students at Durham University and studied Engineering. He came to Durham as a student and made it his home. He was a Civil Engineer and Mining Surveyor. He also served as Observer and Lecturer of Astronomy, as Treasurer to the University, and even as a member of the Senate and the Justice of the Peace of the City of Durham. He lived in the Divinity House, near the Cathedral, until his death in 1898.

Ann Stuart's Mourning Ring

1775

Mourning rings were worn to mark the death of a person. Although we don’t know who owned this ring, we know it is in memory of Ann Stuart, who died in 1775 at age 35. The ring has an inscription which reads 'ANN STUART OBIT 1775 AGE 35' There are locks of Ann’s red hair under the stone. Parish records from the local church of St Oswald record the burial of Ann Stuart in 1775, she was a traveller from Glasgow Scotland, perhaps this ring was made in her memory.

Ellen Caldcleugh’s Name Plate

1800s

There used to be an ironmonger shop which made and sold items made of iron on Silver Street. It was run by a woman named Ellen Caldcleugh. After her father died when she was 15, Ellen took over the family business and cared for her seven younger siblings. the business prospered under her leadership, and continued to be family-run into the 20th century.

Ball and Chain & Electronic Tag

Pre-1900s and 2000s

This heavy ball and chain restrained prisoners and may have come from the nearby Northgate Prison or HMP Durham.

Modern electronic tags monitor an offender's location. These items come from different times, but were used in similar ways and both dropped, or maybe thrown, in the river.

Stories of the Scottish Soldiers

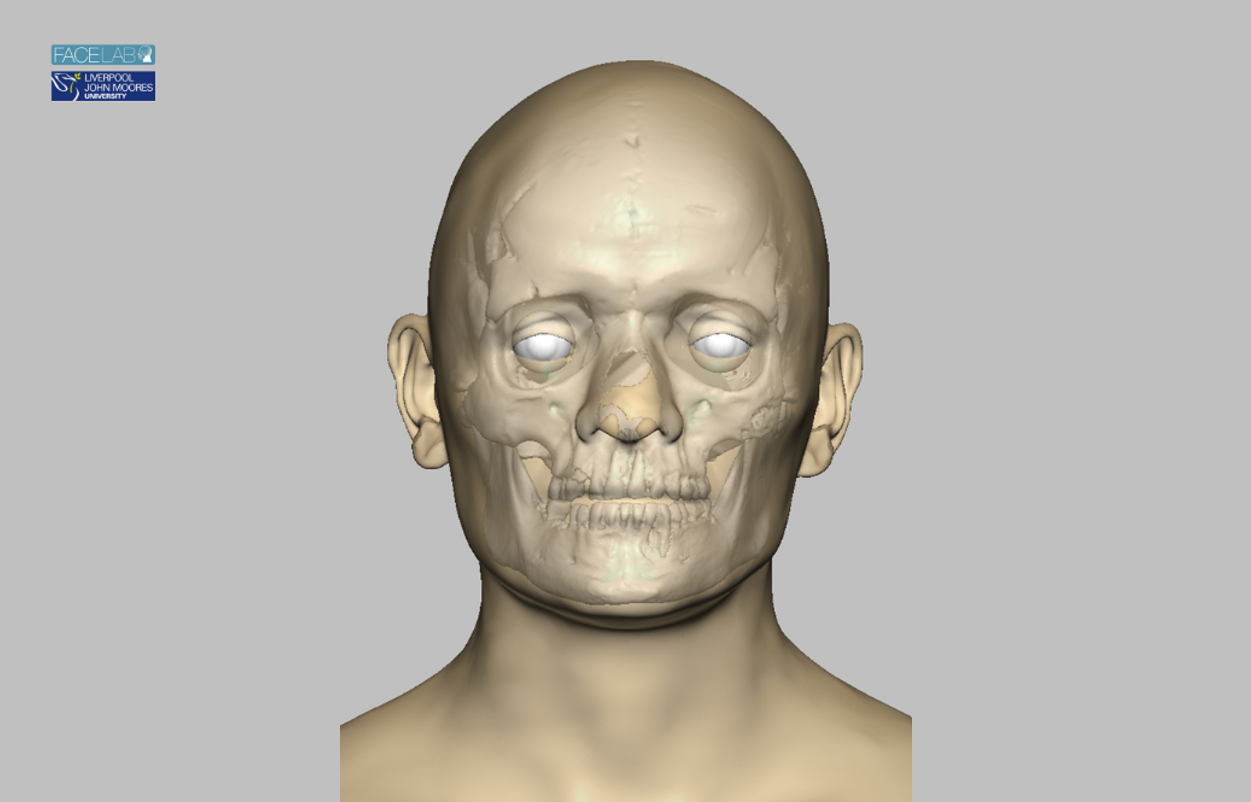

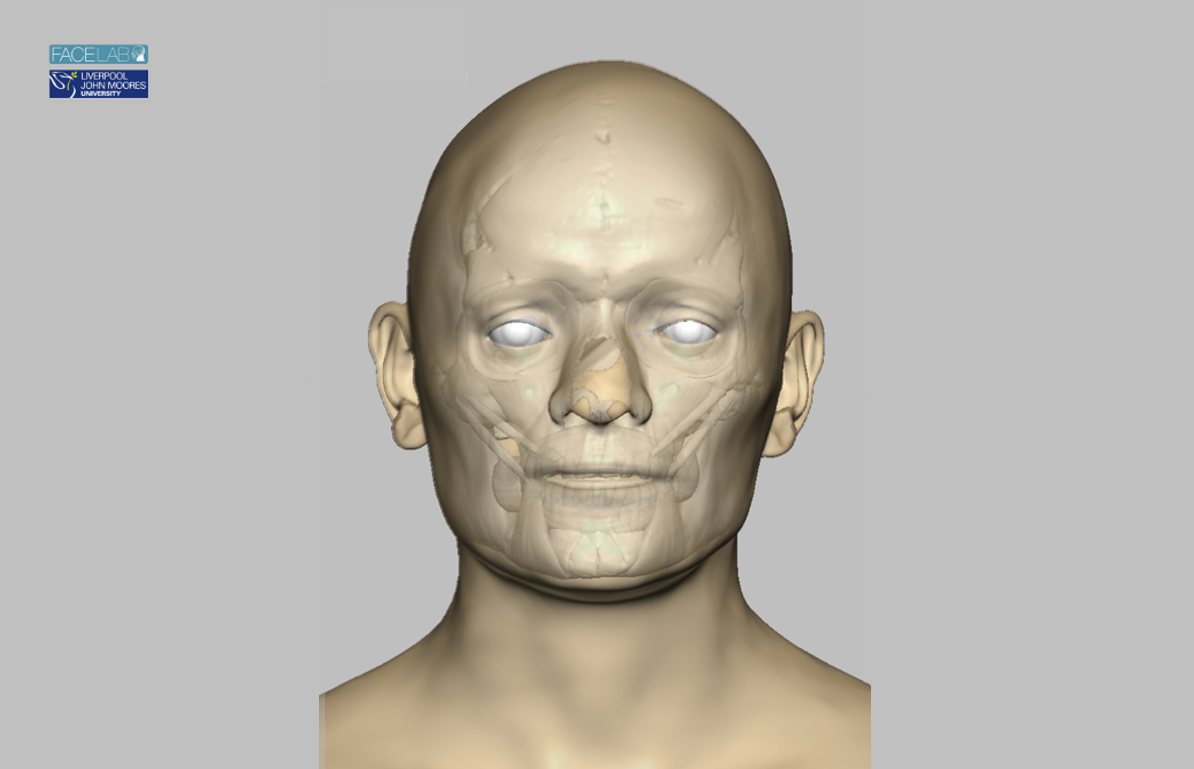

In 2013, during building works here at Palace Green Library, archaeologists discovered two mass graves which had been lost to history. They contained the remains of some of the 1,700 Scottish prisoners of war, who were defeated by the English in the Battle of Dunbar in 1650. This battle was part of the English Civil Wars. Over the next two years, researchers at Durham University used science to piece together their stories.

The soldiers were taken to Durham and imprisoned in the Cathedral, where dysentery spread quickly and many died. The study of their skeletons shows that some of the soldiers were as young as 13. These men and boys were imprisoned for being soldiers in a defeated Scottish army.

Some of the surviving prisoners were sent to work in the industries of the North East, such as in the coal mines of Durham and the saltpans of South Shields. Others were sent abroad to places like New England in the United States of America. Here, they made a home and created a legacy through setting up the Scots Charitable Society in 1657, the oldest charitable organisation in the western hemisphere.

Many did not survive, however, and were buried in mass graves. Their stories are as much a part of Durham’s history as anyone else in this display.

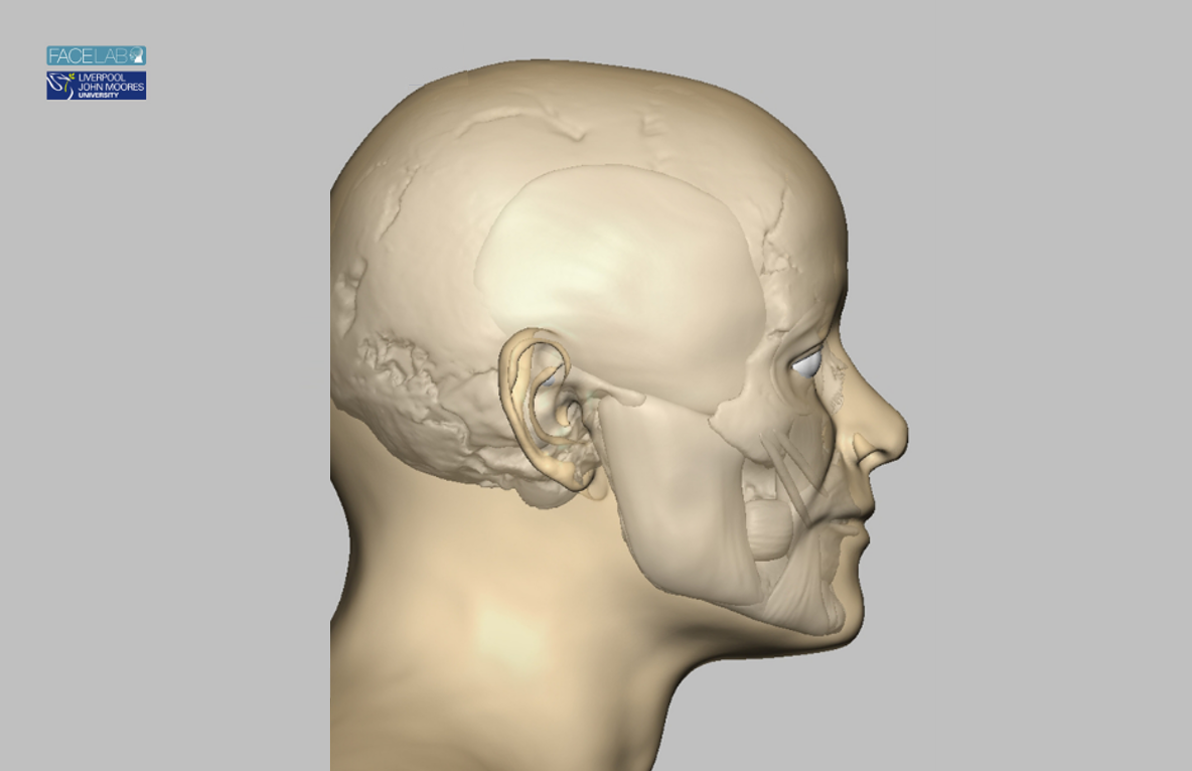

A facial reconstruction of one of the soldiers was created by the Face Lab Research Group at Liverpool John Moores University. This was done using human remains found during excavations at Palace Green Library.

The human remains were first reassembled and then scanned to create a 3D digital model. This reconstruction allows us to come face to face with an imprisoned soldier, who died over 300 years ago in Durham.

Object Gallery

This exhibition was made by Durham University Museum and Artefact Studies students. The objects used are part of the Museum of Archaeology collections.

Exhibition created by:

Benjamin Newman, Catriona Higgins, Georgina Evans, Emily Tarbuck, Prabhtej Sabarwal, Joseph Wisepart, Jing Wen, Chaoying Yu, Gemma Lewis (Museum of Archaeology Curator), Anna Robson (Graduate Intern)

For stories and odd objects that were not included in the physical or online exhibition, visit our podcast on Spotify. Led by Joe Wisepart, who is part of the team that curated Under Durham exhibition, listen to underwater archaeologist Gary Bankhead, Curator Gemma Lewis and Graduate Intern Anna Robson talk about a range of objects, including dentures, lost fossils, and On War Service badges.

Thank you for visiting!