Causes of Collapse

While removing the rubble at the Kasthamandap, we identified that the heavy machinery used in the rescue had ripped through floor levels and foundations that had survived the earthquake.

We also found that the monument’s brick foundations were set in a mud mortar, which had offered flexibility during shocks and that, as a result, earthquakes had not cracked or damaged their two metre deep walls.

The Kasthamandap’s south-west saddlestone and brick pier (Durham UNESCO Chair)

The Kasthamandap’s south-west saddlestone and brick pier (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Scrape marks from heavy machinery deployed in the post-earthquake emergency phase scored across the tile floor of the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Scrape marks from heavy machinery deployed in the post-earthquake emergency phase scored across the tile floor of the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Damage to the foundations of the Kasthamandap from heavy machinery deployed in the post-earthquake emergency phase (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Damage to the foundations of the Kasthamandap from heavy machinery deployed in the post-earthquake emergency phase (Durham UNESCO Chair)

The stability of the monument’s 20 metre high superstructure was designed to rely on the locking of each of its four huge central timber pillars into a stone block set on top of a two metre deep brick foundation column. However, when we cleared the rubble from the Kasthamandap, its north-east stone block was missing from the tiled floor.

Rediscovering the Kasthamandap’s north-east saddlestone (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Rediscovering the Kasthamandap’s north-east saddlestone (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Once these tiles had been removed, the stone was found beneath, securely seated on top of an undamaged brick column. We were able to deduce that the rotten base of the timber pillar in the north-east had been damaged during later conservation work between the 1960s and 1980s. Unfortunately, instead of the entire pillar being replaced and anchored into the foundation block, those responsible for the project had just pushed the tile flooring under its damaged base.

The Kasthamandap’s rotten north-eastern wooden pillar without a tenon (Durham UNESCO Chair)

The Kasthamandap’s rotten north-eastern wooden pillar without a tenon (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Our excavations revealed that this was a major contributing factor in the Kasthamandap’s collapse, because key structural elements were left freestanding and the critical link with the resilient and undamaged foundations lost.

Reconstruction of the original interlinking of the superstructure and foundations of the Kasthamandap (Anie Joshi)

Reconstruction of the original interlinking of the superstructure and foundations of the Kasthamandap (Anie Joshi)

Personal effects recovered within the rubble of the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Personal effects recovered within the rubble of the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Reconstructing the Kasthamandap's History

Before our post-disaster excavations, the Kasthamandap had only been documented through its standing remains and local traditions. Traditionally, its construction had been placed in the twelfth century CE. Furthermore, the installation of Gorakṣanātha shrine, was dated to around 1379 CE.

Foundations and projected elevation of the Kasthamandap after excavations in 2015 (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Foundations and projected elevation of the Kasthamandap after excavations in 2015 (Durham UNESCO Chair)

When the scientific dates for the Kasthamandap’s foundations came back from the laboratory in Stirling, they indicated that it was constructed at some point between the early seventh and early ninth centuries CE, several hundred years earlier than previously thought. This demonstrated that they had not only proved their resilience to the 2015 Earthquake but had survived centuries of earlier seismic shocks.

Dating of timbers also found that there had been a major reconstruction or renovation at the Kasthamandap, at some point between the eleventh and twelfth centuries CE. This illustrates how monuments were built and redeveloped over time, and this reconfiguration of the monument may be where the traditional construction date originates.

The scientific dating of timbers also identified that a lion-headed capital from the monument dated to between the fifth and sixth centuries CE. Earlier than the Kasthamandap's construction, this capital was potentially an original element of an earlier version of the monument, for which we have no archaeological physical evidence; it may have been reused from an earlier monument located within the vicinity of the Kasthamandap; or, it was re-carved from a larger earlier timber from an earlier version of the Kasthamandap or nearby monument.

Such early activity should not be surprising as settlement in Kathmandu is well known from Licchavi period inscriptions, which date to between the fifth and eighth centuries CE. Furthermore, geoarchaeology identified human activity in the region of the Kasthamandap from around 1050 BCE and mapped the Kathmandu Valley’s environmental changes as it transformed from a rural landscape through to a cityscape.

Excavations adjacent to, and recording of the Kasthamandap's foundations (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Excavations adjacent to, and recording of the Kasthamandap's foundations (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Wood samples for radiocarbon dating, cored from the timbers of the Kasthamandap (Anie Joshi)

Wood samples for radiocarbon dating, cored from the timbers of the Kasthamandap (Anie Joshi)

Lion-Headed wooden carved capital radiocarbon dated to between the fifth and sixth century CE (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Lion-Headed wooden carved capital radiocarbon dated to between the fifth and sixth century CE (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Nine-celled mandala layout formed at the Kasthamandap by foundation wall, cross-walls and brick piers (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Nine-celled mandala layout formed at the Kasthamandap by foundation wall, cross-walls and brick piers (Durham UNESCO Chair)

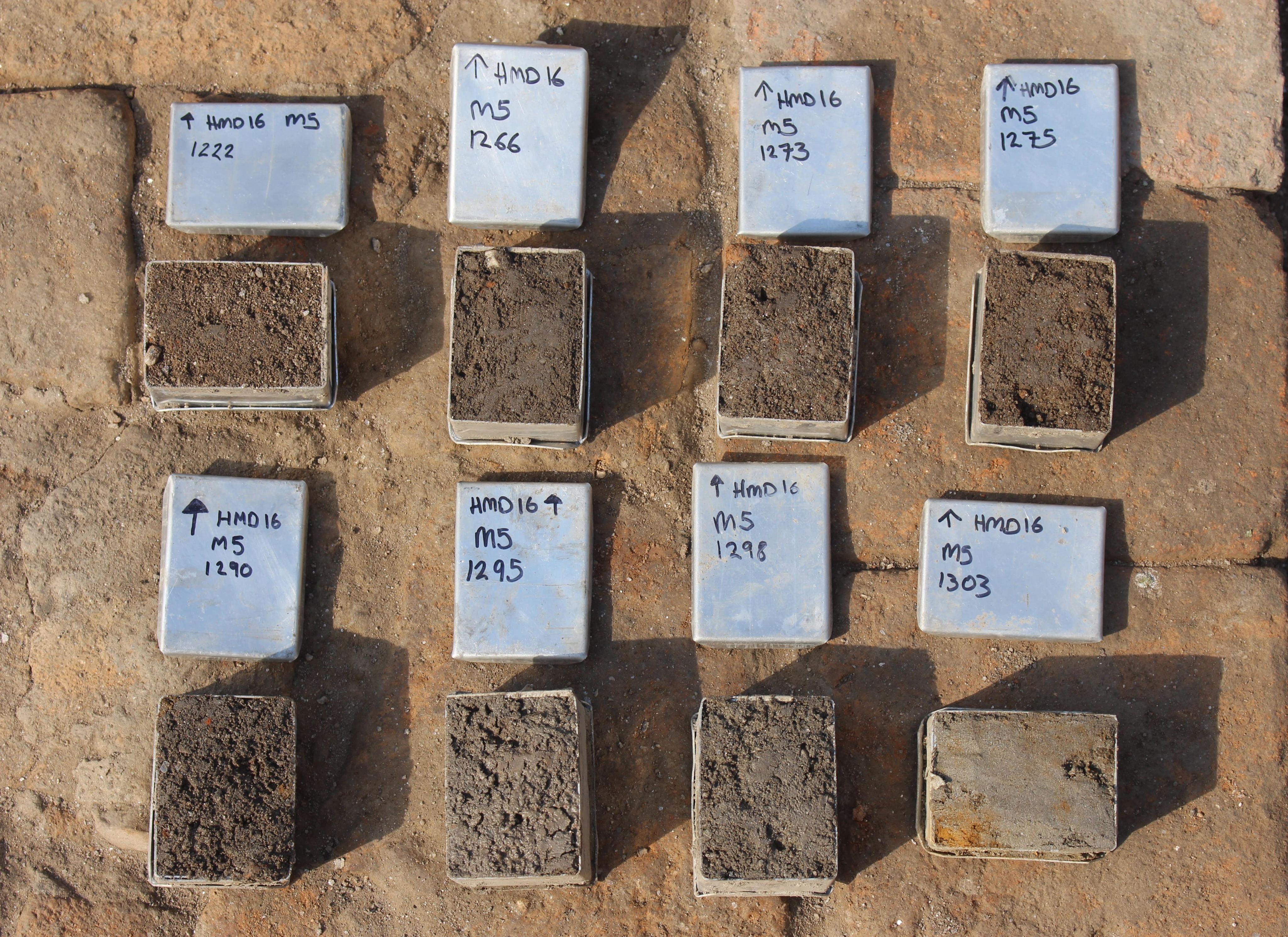

Sanskrit textual traditions record the deposition of different soil mixtures within different cells during the construction of monuments and our analyses has begun to identify their chemical composition, scientifically linking intangible practice to physical remains

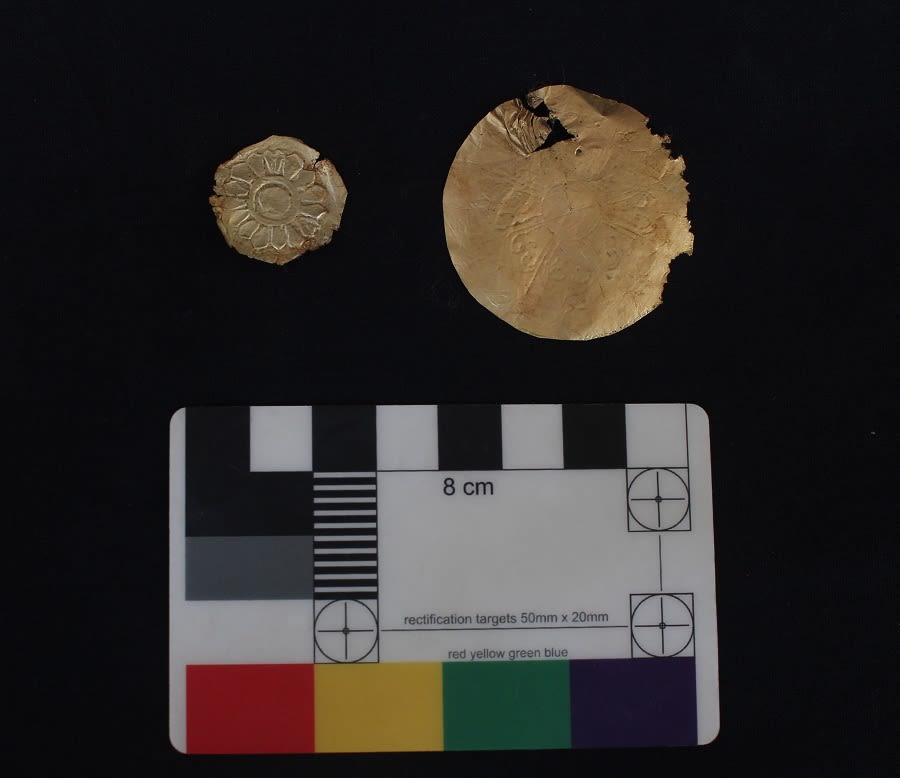

Gold foil discs, with mandala designs, recovered from the socket of the north-east saddlestone (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Gold foil discs, with mandala designs, recovered from the socket of the north-east saddlestone (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Designed with structural resilience, the Kasthamandap’s plan was also created as a sacred representation of the Universe, or mandala. Cross-walls within the foundations created a nine-celled pattern - with a further, nine-celled mandala located within the central cell below the Gorakhnath shrine.

Soil Samples from the Kasthamandap (University of Stirling)

Soil Samples from the Kasthamandap (University of Stirling)

Carefully recording each of the personal effects recovered from the debris of its collapse, we also encountered artefacts from the Kasthamandap’s foundation. Circular gold foil discs, with mandala designs, were found within each of the four saddlestones that had supported the superstructure. The discs were ritual deposits at each of the four corners of the monument for the prosperity and welfare of the building.

Heritage Beneath our Feet

The use of Ground Penetrating Radar also allowed us to look beneath the brick pavements surrounding monuments, such as the Kasthamandap, to identify if there were earlier structures hidden below. Surveying the squares where the collapsed monuments were located, radar signals identified earlier monuments across these historic sites as well as the location of modern pipelines.

This has allowed for the development of Archaeological Risk Maps, which can guide development and repairs within protected heritage zones.

Ground Penetrating Radar survey within Bhaktapur Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Ground Penetrating Radar survey within Bhaktapur Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

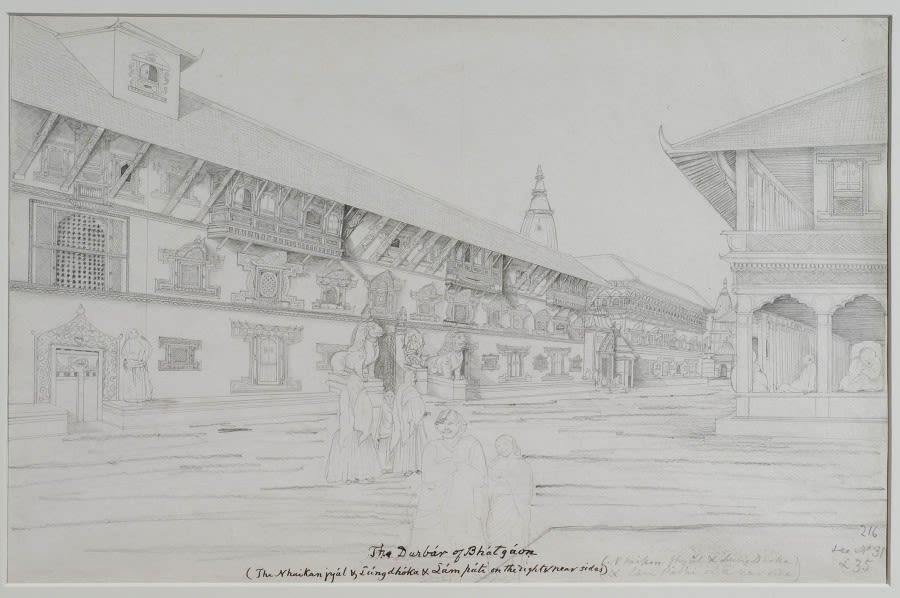

The most spectacular results were within Bhaktapur Durbar Square, where GPR surveys and excavations uncovered the foundations of the Lam Pati, a building that collapsed during the 1934 Bihar Earthquake, were found sealed below successive levels of paving.

Walls uncovered during excavation below the paving within Bhaktapur Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Walls uncovered during excavation below the paving within Bhaktapur Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Bhaktapur Durbar Square, with the Lam Pati visible to the right. Drawn by Raj Man Singh (1797-1865), collected by Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894) (Image Courtesy of the Royal Asiatic Society, Acquisition Number 022.042)

Bhaktapur Durbar Square, with the Lam Pati visible to the right. Drawn by Raj Man Singh (1797-1865), collected by Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894) (Image Courtesy of the Royal Asiatic Society, Acquisition Number 022.042)

Monks processing through Bhaktapur Durbar Square as an earlier paving is identified below the current ground surface (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Monks processing through Bhaktapur Durbar Square as an earlier paving is identified below the current ground surface (Durham UNESCO Chair)

GPR survey and targeted excavations have also identified previously unknown subsurface heritage within Patan and Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Squares, as well as within the courtyard of Changu Narayan Temple.

Earlier structures found through excavation adjacent to, and running under, the Trailokiya Mohan Temple, Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Earlier structures found through excavation adjacent to, and running under, the Trailokiya Mohan Temple, Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Recording structures below the paving, Bhaktapur Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Recording structures below the paving, Bhaktapur Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Uncovering new wall alignments between the Jagannath and Gopinath Temples, Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Uncovering new wall alignments between the Jagannath and Gopinath Temples, Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

An earlier structure, on a different alignment, running under the Maju Dega temple (Durham UNESCO Chair)

An earlier structure, on a different alignment, running under the Maju Dega temple (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Successive construction episodes identified below the ground surface close to Jaisidewal temple, south of Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Successive construction episodes identified below the ground surface close to Jaisidewal temple, south of Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Walls and pavements uncovered below the surface within the courtyard of Changu Narayan temple (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Walls and pavements uncovered below the surface within the courtyard of Changu Narayan temple (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Seismic Safety

During our post-disaster fieldwork in Kathmandu, it became clear that additional collaborations were needed from a wide-range of disciplines. We have now co-designed a new approach that built on the links between archaeologists, geoarchaeologists and architects by integrating geo-technical and structural engineers, as well as 3D visualisation specialists and social scientists.

GPR survey in the courtyard of Changu Narayan temple (Dr Armin Schmidt)

Our new pilot methodology was sponsored by the British Academy’s Global Challenges Research Fund programme ‘Cities and Infrastructure’ and our project, ‘Reducing Disaster Risk to Life and Livelihoods by Evaluating the Seismic Safety of Kathmandu's Historic Urban Infrastructure’ (CI170241), aims to assess, evaluate and improve the seismic safety of historic urban infrastructure within Kathmandu's UNESCO World Heritage sites in the face of earthquakes, while preserving Kathmandu’s architectural and historical authenticity, traditions and livelihoods.

Excavations in advance of borehole drilling near to Jaisidewal (Durham UNESCO Chair)

The team undertook GPR survey to identify areas of potential archaeological features and archaeological excavations recorded evidence of earlier phases of historic settlement within the Kathmandu Valley. This allowed for the drilling of geotechnical boreholes, which would otherwise have damaged this valuable and finite historic evidence. The soil cores from this drilling allowed for an understanding of the underlying stability of the earth on which monuments are built as well as helping model earthquake motion in these locations.

Structural engineers undertaking analysis of Changu Narayan Temple (Durham UNESCO Chair)

This information is now being linked to an assessment of historic construction practice, analysing materials used and how foundations were linked to their superstructures. As many plans of historic monuments are incomplete, or were not available before the 2015 Gorkha Earthquake, 3D constructions of superstructures are being generated through the use of historic photographs and crowd-sourced imagery.

Community debriefing meeting at Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Local residents and stakeholders are also being consulted, including residents, craftspeople, tour operators, businesses and tourists, to map and promote the traditional processes of procurement, construction, recycling and maintenance, and their community values as well as patterns of visitor spend and behaviour at historic sites.

GPR survey in the courtyard of Changu Narayan temple (Dr Armin Schmidt)

GPR survey in the courtyard of Changu Narayan temple (Dr Armin Schmidt)

Excavations in advance of borehole drilling near to Jaisidewal (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Excavations in advance of borehole drilling near to Jaisidewal (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Structural engineers undertaking analysis of Changu Narayan Temple (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Structural engineers undertaking analysis of Changu Narayan Temple (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Community debriefing meeting at Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Community debriefing meeting at Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square (Durham UNESCO Chair)

3D visualisation of Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square from web-scraped imagery (Professor Andrew Wilson and University of Bradford)

3D visualisation of Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square from web-scraped imagery (Professor Andrew Wilson and University of Bradford)

Borehole drilling being undertaken within the courtyard of Changu Narayan temple (Durham UNESCO Chair).

Borehole drilling being undertaken within the courtyard of Changu Narayan temple (Durham UNESCO Chair).

Students from Tribhuvan University undertaking community engagement surveys (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Students from Tribhuvan University undertaking community engagement surveys (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Heritage at Risk

The Heritage of South Asia faces an increasing number of threats, ranging from natural disasters, such as earthquakes, to the impacts of accelerated development and conflict. It has also become increasingly apparent that the promotion and development of heritage sites can offer social and economic benefits for stakeholders and local communities. Although complex, the delivery of such benefits is challenged by a general lack of co-ordination between local stakeholders, researchers, heritage managers and local government administrators in the promotion and protection of heritage sites within development programmes.

Group discussions during the international workshop ‘Heritage at Risk 2017' (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Group discussions during the international workshop ‘Heritage at Risk 2017' (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Reiterating existing the Department of Archaeology (Government of Nepal)’s Conservation Guidelines for Post 2015 Earthquake Rehabilitation, it is hoped that these resolutions will combat the many challenges facing heritage sites in Nepal, and throughout South Asia, leading to its enhanced protection.

Stakeholders at the international workshop ‘Heritage at Risk 2017' (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Stakeholders at the international workshop ‘Heritage at Risk 2017' (Durham UNESCO Chair)

To raise awareness of these threats and challenges, we held an international workshop ‘Heritage at Risk 2017: Pathways to the Protection and Rehabilitation of Cultural Heritage in South Asia’ in Kathmandu in September 2017, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (UK)’s Global Challenges Research Fund, and coordinated by Durham University’s UNESCO Chair in Archaeological Ethics and Practice in Cultural Heritage, the Department of Archaeology (Government of Nepal), ICOMOS (Nepal) and UNESCO’s Kathmandu Office.

Delegates at the international workshop 'Heritage at Risk 2017' (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Delegates at the international workshop 'Heritage at Risk 2017' (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Resolutions included the evaluation of foundations of damaged and collapsed heritage sites through multi-disciplinary investigations. While investigating the issue of seismic stability, the workshop’s participants suggested that the foundations of monuments should be retained as far as possible if undamaged. As well as urging archaeological investigations before subsurface interventions at historic sites, the resolutions called for the development of a network of South Asian experts and key disaster responders to be rapidly mobilised to protect and rehabilitate sites and monuments following natural and cultural disasters as well as conflict.

Archaeology for the Past, Present and Future

Our team are continuing to examine the artefacts and samples from the Kasthamandap, discovering new insights into the monument’s history - insights which could have been lost if rapid reconstruction had taken place. Our archaeological work has shown how vulnerable the monuments of Kathmandu are from earthquakes, but also the equally great risk from the response to such disasters.

While humanitarian efforts are of paramount importance, heritage protection and the recovery of historic material are also critical in the aftermath of a disaster. To develop this capacity, the team ran a live exercise at a collapsed monument in a safe environment.

Fieldwork in Kathmandu has demonstrated that rescue archaeology can uncover the previously unknown stories of iconic monuments and that we can provide critical information as to why monuments collapsed. It has also demonstrated that archaeologists can play a key role in training first responders to protect heritage in the immediate aftermath of an earthquake, thus ensuring that valuable historical evidence is not further destroyed.

This provided an ideal opportunity for first-responders, including site managers, emergency services and the army, to develop skills and knowledge of the careful removal of rubble and artefacts without specialist tools, whilst prioritising the recovery of human life. We also trained them to recycle historic materials, as the earlier post-disaster emergency response resulted in the dumping of millions of dollars' worth of reusable historic bricks.

Post-disaster excavation training at Gurujyu Sattal Pashupati (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Post-disaster excavation training at Gurujyu Sattal Pashupati (Durham UNESCO Chair)

View down onto the cleared foundation of the Gurujyu Sattal during post-disaster excavations (Dr Paolo Forlin)

View down onto the cleared foundation of the Gurujyu Sattal during post-disaster excavations (Dr Paolo Forlin)

At a time when heritage sites across the world are at risk from natural disaster and conflict, we hope that the approaches and methodologies pioneered in Kathmandu can be successfully transferred elsewhere.

Post-disaster excavations piloted at the damaged Kruys Kerk within Jaffna Fort, Northern Sri Lanka (Durham UNESCO Chair and Professor Prishanta Gunawardhana)

Post-disaster excavations piloted at the damaged Kruys Kerk within Jaffna Fort, Northern Sri Lanka (Durham UNESCO Chair and Professor Prishanta Gunawardhana)

Resilience Within the Rubble

Our excavations have shed new light on the early rituals associated with the construction of monuments in the Kathmandu Valley and have demonstrated that the Kasthamandap and other historic structures had strong foundations, undamaged by centuries of earthquakes.

The continuation of festivals, rituals and everyday life in and around these monuments in the aftermath of the earthquake also demonstrates the resilience of its local communities.

When digging at the site, it also became immediately apparent that, although in ruins, the Kasthamandap still remained a focus of daily activity and ritual in Kathmandu.

The footprint of the monument still hosts a market, with marigold garlands, as well as fruit and vegetables for sale. Ritual also continues, with ceremonies continuing on the levelled brick, and festivals and processions following traditional routeways of movement around the monument and city.

Marigold garland sellers beside the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Marigold garland sellers beside the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

A Pandit amongst the ruins of the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

A Pandit amongst the ruins of the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Procession of Lord Ganesh around the ruins of the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Procession of Lord Ganesh around the ruins of the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Marigold garland sellers and archaeologists at the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Marigold garland sellers and archaeologists at the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

These economic and ritual activities again highlight the intangible value of the Kasthamandap to its communities, even after its collapse, and the continued importance of this monument and its place in the daily rhythms of the city and in the vibrant social dynamics of Kathmandu today.

Rebuilding the Kasthamandap

Our research results have been used by the Kasthamandap Reconstruction Committee to establish the best ways to repair the monument. This has highlighted the value of traditional and indigenous construction techniques and skilled craftspeople and artisans for seismic safety and integrity. This includes the use of mud mortar within foundations and the installations of copper plates to reduce risks from damp and rot, as well as to deter insect damage. Uncovering previously ‘lost’ or neglected vernacular traditions and indigenous knowledge has directly addressed significant concerns expressed by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) that authenticity in Kathmandu is unnecessarily being destroyed, and intangible value disrupted by the ways in which restoration work and international disaster relief efforts were being implemented.

While the programme of rescue excavations has uncovered a deep and previously unknown past, the Kasthamandap continues to be relevant to diverse communities in the present. The reconstruction has not only rebuilt a monument and filled a gap in the skyline, it has also strengthened the bonds between communities and the Kasthmandap through intangible traditions and rituals.

Carving new timber elements for the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Carving new timber elements for the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

One of the newly installed copper plates below a large central timber post (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Photo by Wolfgang Hasselmann on Unsplash

One of the newly carved central timber posts of the Kasthamandap being transported by the community to the monument site (Kai Weise)

One of the newly carved central timber posts of the Kasthamandap being transported by the community to the monument site (Kai Weise)

The living goddess Kumari sanctifying timber posts prior to their installation at the Kasthamandap (Kai Weise)

The living goddess Kumari sanctifying timber posts prior to their installation at the Kasthamandap (Kai Weise)

The Kasthamandap is an example of how interdisciplinary study and community engagement can lead to successful and meaningful authentic rehabilitation of Kathmandu’s historic monuments.

While there are many lessons learned for decision makers, practitioners, academics, crafts people and residents, there are a number of broader lessons learned, which are relevant for the Kathmandu Valley and beyond. Some of these were developed within the UK National Commission for UNESCO’s Policy and Practice Brief on ‘Heritage, Disaster Response and Resilience’ with Praxis and AHRC.

From this, the key insights were:

ONE. Heritage – cultural and natural, tangible and intangible – is an invaluable resource for emergency preparedness and recovery.

TWO. The effectiveness of disaster resilience and recovery depends heavily on the implementation of inclusive, locally and culturally appropriate approaches.

These lessons learnt from post-disaster fieldwork in the Kathmandu Valley are also relevant to other pressing global challenges.

This was discussed during the recent International Co-Sponsored Meeting on Culture, Heritage and Climate Change (ICSM CHC), sponsored by the IPCC, UNESCO, and ICOMOS, where the integration of ‘scientific’ and indigenous knowledge systems are helping our understandings of past and future adaptations for the protection and preservation of cultural heritage and their communities in the face of climate change.

“The Kasthamandap has proved the importance of archaeological and scientific studies, especially for those cases where history and culture are embedded below the surface

This helped to scientifically resolve the ever existing debate about the date of construction of the Kasthamandap and the history of the Kasthamandap was pushed further back in time.

Furthermore the investigation also indicated the probable reasons behind the collapse of the Kasthamandap. It was clear that the lack of timely maintenance as well as improper interventions in the past was instrumental in the collapse of the Kasthamandap.

The Kasthamandap is but a tip of the iceberg. There are numerous monuments and sites in Nepal awaiting for proper archaeological studies that could uncover great information about their past.

In absence of strong heritage policy in Nepal, the heritage structures are continuously being encroached erroneously"

Mr Rajesh Shakya MP

Mr Rajesh Shakya, MP Bagmati Province, and Chairperson of the Kasthamandap Reconstruction Committee, holding a gold foil disc with mandala design. These gold foil discs were placed into the mortices of the four central saddlestones of the Kasthamandap prior to the large timber posts being re-erected (Kai Weise).

Mr Rajesh Shakya, MP Bagmati Province, and Chairperson of the Kasthamandap Reconstruction Committee, holding a gold foil disc with mandala design. These gold foil discs were placed into the mortices of the four central saddlestones of the Kasthamandap prior to the large timber posts being re-erected (Kai Weise).

Hoisting timber elements for the reconstruction of the Kasthamandap (Kai Weise)

Hoisting timber elements for the reconstruction of the Kasthamandap (Kai Weise)

Carving new timber elements with reference to original timber salvaged from the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Carving new timber elements with reference to original timber salvaged from the Kasthamandap (Durham UNESCO Chair)

Placing a large new central timber post into its saddlestone (Kai Weise)

Placing a large new central timber post into its saddlestone (Kai Weise)

Wood carving within the Kasthamandap (Kai Weise)

Wood carving within the Kasthamandap (Kai Weise)

Craftspeople reconstructing the Kasthamandap (Kai Weise)

Craftspeople reconstructing the Kasthamandap (Kai Weise)

One of the several Vajrayana rituals undertaken within the Kasthamandap during its reconstruction (Kai Weise)

One of the several Vajrayana rituals undertaken within the Kasthamandap during its reconstruction (Kai Weise)

The reconstructed Kasthamandap (Kai Weise)

The reconstructed Kasthamandap (Kai Weise)

"Disasters, human or natural, very often overwhelm planned responses, a situation that in turn compromises heritage research and protection agendas...archaeology and heritage science, although infrequently mobilized, are uniquely placed to assist in providing a fuller understanding of the impact of climate change on urban infrastructure in the past; they also facilitate reflection on lessons of adaptation and resilience for modern cities and their inhabitants”

Coningham and Weise (2022: 34)

In the 'Global Research and Action Agenda' of the UNESCO-IPPC-ICOMOS International Co-Sponsored Meeting on Culture, Heritage and Climate Change

Resilience within the Rubble is a collaborative exhibition developed by Durham University’s UNESCO Chair in Archaeological Ethics and Practice in Cultural Heritage, the Department of Archaeology (Government of Nepal), the University of Stirling and Durham University’s Oriental Museum. The exhibition was curated by Prof Robin Coningham, Dr Christopher Davis, Mr Kosh Prasad Acharya, Mr Ram Bahadur Kunwar, Dr Craig Barclay, Mrs Rachel Barclay, Ms Anie Joshi, Mr Kai Weise, Mrs Aruna Nakarmi and Prof Ian Simpson. The online exhibition was developed with support from Mr David Wright.

This online exhibition was developed from previous exhibitions held at Durham University's Oriental Museum and at Dhukuti, part of the Hanuman Dhoka Museum.

The post-disaster archaeology at the Kasthamandap, and across Kathmandu, would not have been possible without the support and interest of the communities of Kathmandu, and the dedication of field team members, including:

Mrs Manju Singh Bhandari, Dr Paolo Forlin, Ms Anouk LaFortune Bernard, Dr Jennifer Tremblay-Fitton, Mr Bhaskar Gyawali, Prof K. Krishnan, Dr Mark Manuel, Mrs Saubhagya Pradhananga, Dr Nina Mirnig, Mrs Mangala Pradhan, Dr Armin Schmidt and Dr Keir Strickland.

We are also grateful to the following institutions for field support: the Department of Archaeology (Government of Nepal), ICOMOS (Nepal), Durham University, University of Stirling and UNESCO Kathmandu, as well as to our partners: Pashupati Area Development Trust, Kathmandu Metropolitan Council, Lalitpur Metropolitan Council, Bhaktapur Municipal Council, M.S. University of Baroda (India), University of La Trobe (Australia), Central Cultural Fund (Government of Sri Lanka), Department of Archaeology and National Museum and Library (Government of Myanmar) and Lumbini Buddhist University and Tribhuvan University (Nepal).

We are very grateful to these institutions, as well as the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Dr Abdul Azeem, Professor Prishanta Gunawardhana and the late Charles Allen, for their support and contributions to this exhibition.

This exhibition is part of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (UK) Global Challenges Research Fund (AH/P006256/1), the National Geographic Society Conservation Trust Award (#C333-16) sponsored Project Can We Rebuild the Kasthamandap? and the British Academy Global Challenges Research Fund’s Project Reducing Disaster Risk to Life and Livelihoods by Evaluating the Seismic Safety of Kathmandu's Historic Urban Infrastructure (CI170241).

The project and exhibition received additional financial support from UNESCO Kathmandu, the Alliance de Protection du Patrimoine Culturel Asiatique, the Pashupati Area Development Trust and Durham University’s Institute of Medieval and Early Modern Studies (IMEMS).