Hidden Stories from

the River Wear

Exploring 1000 years of

Durham History

For centuries, people have been building their cities and living their lives around rivers. But how often do we take a moment to wonder: what could be lying beneath their surface?

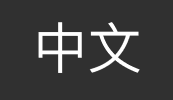

For hundreds of years, thousands of objects have been gathering at the bottom of the River Wear – the river crossing the city of Durham. Thousands of weird and wonderful objects have been recovered from its depths by an underwater archaeologist: Gary Bankhead.

Every object has a hidden story to tell: a story about the rich and fascinating history of Durham’s people. Preserved in the river’s watery depths, these objects have stood still as the city thrived and changed.

In this exhibition, we have selected some of the most playful, romantic and unusual objects, and we cannot wait to share them with you! Look out for the People of Durham objects throughout the exhibition, telling the stories of objects and people connected with the city of Durham.

How these objects came to this fate remains a mystery. Perhaps they fell from one of the peddlers’ stalls that crowded Elvet Bridge (one of Durham’s most lively bridges) on a busy market day in Medieval Durham. Certainly, in the hustle and bustle of trade, a brooch or pendant could have easily been lost. A toy might have slipped from a child’s hand, or, perhaps, some objects were tossed into the river as tokens of love or good fortune.

Let's dive in!

"Hello! I'm Gary Bankhead. Follow me to explore the River Wear collection!"

Gary Bankhead and the River Wear Collection

That’s right – Gary Bankhead is all of these things! A remarkable man who has discovered an equally extraordinary collection of objects in the depths of the River Wear in Durham.

Since 2007, Gary has been diving under Old Elvet Bridge, bringing to the surface over 13,500 objects from as early as the 12th century. In 2008, he created the Dive into Durham project, aiming to research, catalogue and display these objects.

Alongside his underwater adventures, Gary has been a firefighter for over thirty years. He is heavily involved in Durham’s local community and has raised over £100,000 for charities, has given over 150 talks and lectures, and gifted his research of the River Wear collection to the people of Durham.

Dive with us into the hidden stories of the River Wear to discover Gary’s treasures and learn more about their fascinating history!

Before we begin, lets explore more of Durham itself!

Click on the location points to learn more about Durham's sites and the bridges where Gary discovered his vast collection of artefacts!

To view the map in full-screen, simply click the full-screen button in the bottom right-hand corner.

To view the map in Chinese, simply click the arrow on the right-hand side of the map.

Watch the video below to find out how the objects may have ended up in the river!

Weird and Wonderful

The River Wear collection has a wealth of ‘weird and wonderful’ objects that reveal the hidden stories of Durham and its people, although there are a few objects that stand out from the rest! From buried treasure to gruesome dentures, they provide a glimpse into Durham’s bizarre and sometimes darker past.

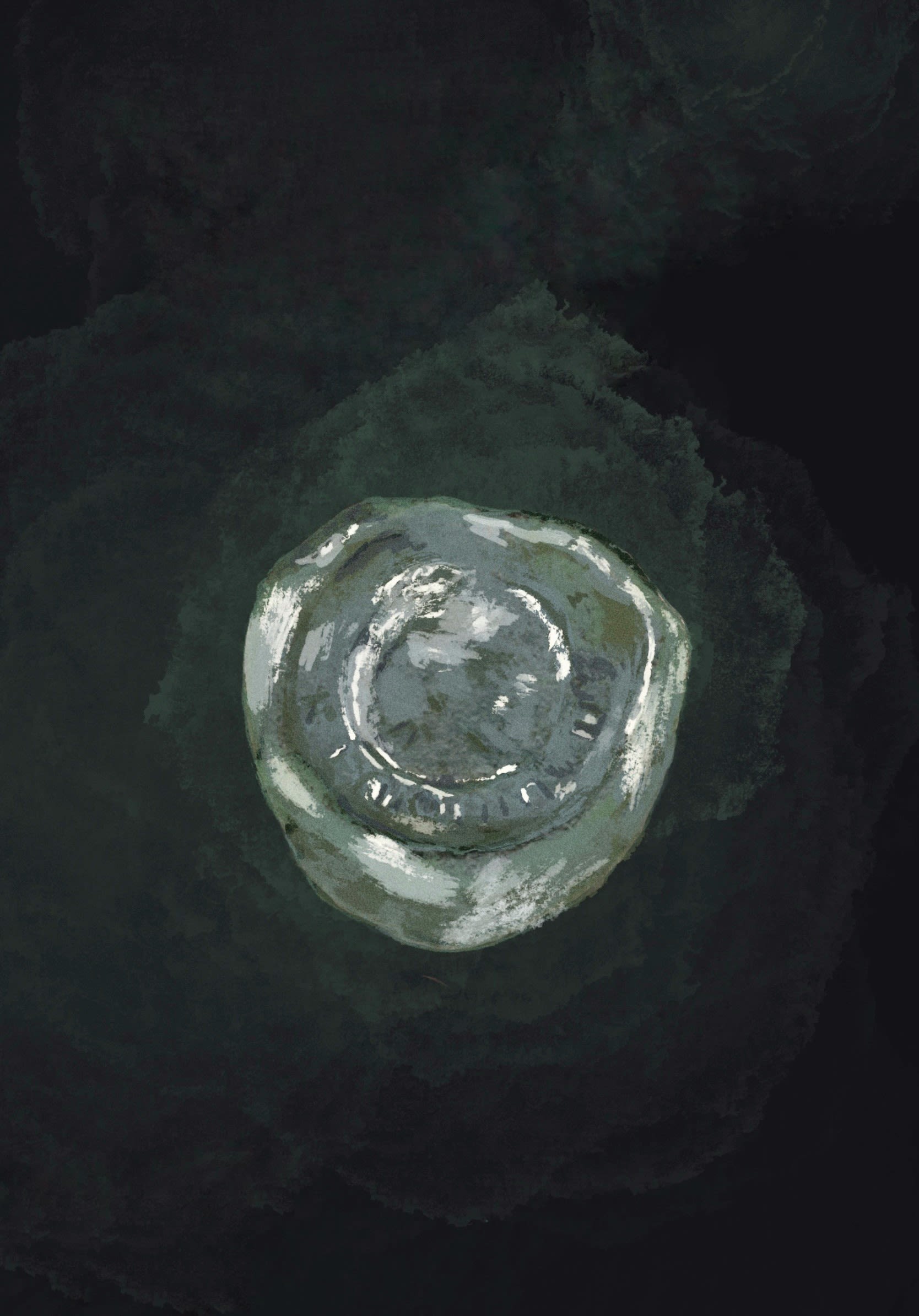

Jetton

16th century Lead jetton, possibly part of a witch bottle.

Jettons are circular discs made of metal and are often decorated with a design or inscription. In the Medieval period, they were used as currency or to perform calculations using a counting board.

Gary’s research into this jetton suggests that it could be part of a witch bottle! Witch bottles were used during the 16th and 17th centuries as a cure for bewitchment. A variety of ingredients were placed in the bottle, including pins, human hair, fingernails and even urine. The bottle was then deposited in a ditch or near a river.

Jettons, coins, and charms were also thrown into rivers as offerings for protection or to ensure good luck.

Pigeon Ring

c. 1919 Copper-alloy pigeon ring with the inscription ‘WHS 19POO40’.

During the 19th century, pigeon racing was a popular sport, from coal miners to royalty. Did you know that ten racing pigeons were released in Durham on the 17th April 2021, to commemorate the life of His Royal Highness, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh?

Racing pigeons are often released hundreds of miles from their homes. The owner records the pigeon’s flight by stamping the time on a ring attached to the pigeon’s leg. The stamp is then compared with other racing pigeons to determine the fastest bird. This particular pigeon ring has the inscription ‘WHS 19POO40’ which is associated with the Welsh Homing Society.

Anthropomorphic Lion

11th – 15th century Brass candle holder in the shape of a lion.

This anthropomorphic lion is thought to be the foot of a candlestick or candle holder. Anthropomorphic means it has both human and animal characteristics, which is why this lion looks a little unusual! In the Medieval period, the lion was considered the “king of beasts” and symbolised bravery, strength and nobility.

Have a look at this clip of Gary discovering the lion!

"I clearly remember finding the 'lion' as its discovery came right at the end of my dive when I was getting low on air. I was on a good 'medieval' layer of artefacts, so I knew that the next discovery from it may be exciting and wanted to push the limits. When I first saw it, I couldn't make sense of what it was. I could see its little smiling face looking up at me, but it wasn't until I saw its mane that I realised it was a lion. At that moment, it was as if we exchanged greetings." - Gary Bankhead

Georgian Intaglio Seal Matrix

18th century. Decorated with a gilt blue glass impression of a satyr engaging in coitus with a female nymph.

Traditionally seals were used by nobility, officials and bishops to authenticate important documents. The bottom of the seal had a coloured stone engraved with an image or design which would be pressed into wax. The engraved intaglio would then create an impression.

The Georgian intaglio on this seal depicts an explicit scene between a nymph and a satyr. The origin of this seal is a mystery, but it is likely that the inclusion of the erotic image was intended to be humorous or to shock the unwitting recipient. It is certainly an intriguing discovery.

The base of this object had to be blurred due to its explicit nature.

Dentures

c. 1880s Upper dentures made from porcelain and vulcanite.

Visiting the dentist is not an experience that many people enjoy. It can often be uncomfortable, and even a little painful. But compared to the dental practices of the past, modern-day dentists are almost fun! In the early 18th century, rotten teeth would often be pulled out by barbers, using an assortment of gruesome instruments. The wealthy would wear dentures fashioned from animal bone or human teeth. By the 19th century, human teeth were replaced with ivory and wood.

The teeth in these dentures are made of porcelain and the gums of vulcanite, which was a cheap rubber. This made the dentures much more comfortable and visually pleasing. Upper dentures would have been secured to the roof of the mouth by a suction disc. Although apparently this did not prevent these particular dentures from being lost in the river!

“Have you ever heard of an obituary ring? Follow me to find out more.”

People of Durham

Ann Stuart Obituary Ring

c. 1775 Gold ring, with rock crystal stone, covering a lock of red hair, on an ivory backing. The band reads “ANN STUART OBIT 1775 AGE 35”.

Obituary rings were common in the Post-Medieval period. This one belonged to someone who was mourning the death of an Ann Stuart, who died in 1775 at the age of 35. In 1775 there are only two ‘Ann Stuarts’ whose deaths are recorded. It is likely that there were many Ann Stuarts that died that year, but their deaths haven’t been recorded.

One of the women was named Mary Ann Stuart (it probably wouldn’t have been unusual for her to have been known as Ann to loved ones, people had nicknames in the olden days too). Her will tells us that she was wealthy and unmarried. It states “I [..] give to the several persons following ten guineas each for a Ring”. This would be the equivalent to around £900 today. She bequeathed this amount to ten people in various parts of the country, including Derbyshire, Norfolk, Dewsbury and Dorset. The potential existence of 10 mourning rings could suggest that the one found in the River Wear was made to commemorate Mary Ann. She was buried at All Hallows By The Tower church in London.

Sadly, there is very little information on the other Ann Stuart who is recorded as having died in 1775. She was buried in Banwell, Somerset on the 15th of September 1775, and is simply listed in Church records as a ‘sojourner’, meaning that she probably didn’t live in the area.

Childhood

A child’s imagination can turn anything into a toy, from playing with sticks and pieces of string to skipping pebbles across the river – the possibilities are endless! Very few toys survive to be unearthed by archaeologists. Gary's finds represent a toy box of social history, play and learning. We may never know who owned the toys, but we can imagine how they treasured and played with them. It is also surprising how some toys have changed over the centuries and how many have stayed the same.

Homer Simpson Toy

21st century, Plastic

This 21st-century toy may look familiar to you! Homer is the most modern object in our exhibition. The figure was mass-produced to promote the 2007 The Simpsons Movie. Toys are constantly evolving, and makers and manufacturers are always looking for new designs and new materials. Lead toys, which were poisonous, were replaced by other metals and then by plastic. Some plastic toys have also proved to be toxic and harmful to the environment. What materials will be used in the future?

Toy Aeroplane

20th century, Tin and pewter

This toy is inspired by a World War II (1939-1945) aircraft. Toys often replicate real objects, and this plane would have been able to fly with a little bit of imagination, a child’s hand and some replica aeroplane noises! At the time, this might have been the must-have toy and would have been just as exciting as the release most toys have today.

Native American Figure

20th century, Lead

This is a toy Native American figure from the first half of the 20th century. Toys of Native Americans became popular in the 20th century following the rise of Western films and books that commonly had ‘Cowboys vs Indians’ battling for land and dominance in the western United States. Perhaps the child who played with this toy acted out fights from these movies, with matching lead cowboys. ‘Cowboys vs Indians’ has since become a symbol of racial stereotypes surviving from the colonial period in the United States. The toy’s inclusion in this exhibition aims to highlight how racial stereotypes have been entrenched into popular culture over the last century.

Toy Skirt

16th - 17th century, Lead

All that remains of this doll is her skirt! Perhaps it was damaged in the river, or perhaps it was thrown away when the child lost the rest of the doll. Many dolls during this period were made with scrap fabric and are therefore less likely to have survived. Today’s dolls have beautiful hair to brush, nappies to change and bottles for feeding. But how do you think children would have played with this doll at the time? Maybe she walked through the gardens, looked after other dolls, or perhaps she went on adventures with other toys.

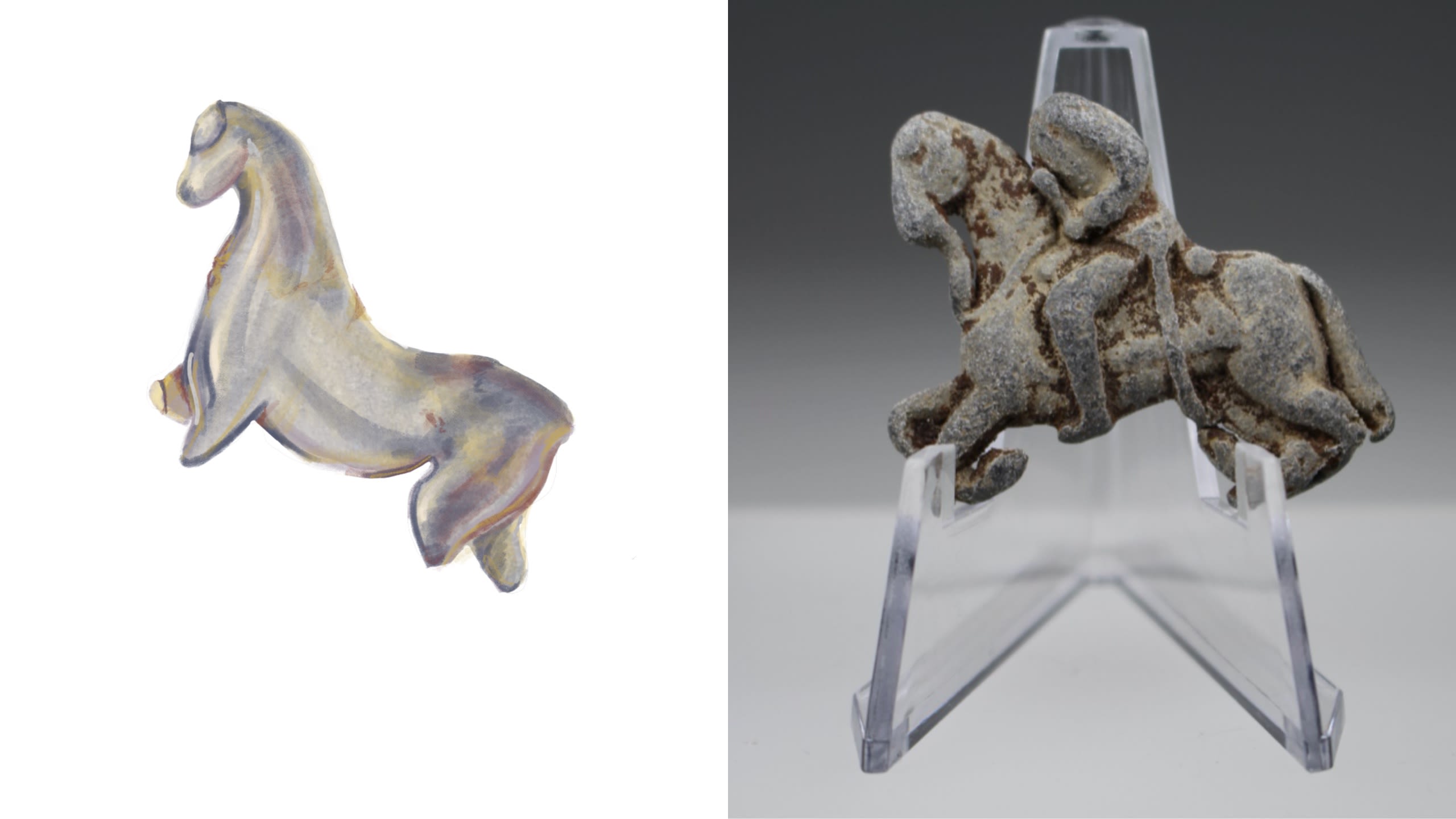

Toy Horse

17th century, Lead

Gary’s research into this toy horse uncovered international links. A very similar example was found in Jamestown, Virginia in the United States. From the late 15th century onwards, many people embarked on the long journey from the United Kingdom to settle in America. Perhaps a local Durham family decided to relocate and took a similar treasured toy with them. Or maybe the design was created in the colonies and exported back to England.

Toy Knight

16th - 17th century, Lead

When this toy was made, knights were starting to be replaced by professional armies and soldiers. During the Medieval period, the idea of chivalrous knights developed, and kings and noblemen aspired to be gallant knights. This is an example of popular culture informing the creation of toys even in the 17th century.

Toy Soldier with Musical Instrument

19th century, Lead

Toy soldiers have a long history. Did you know the oldest toy soldiers were found in Ancient Egyptian tombs? Military strategists used miniature soldiers, very similar to toys, to plan out their next move. Napoleon Bonaparte, French Emperor and successful military leader, first popularised the use of miniature soldiers to organise his armies. Some toy soldiers were for playing. A child would march this toy into battle, or into celebration.

Homer Simpson Toy

21st century, Plastic

This 21st-century toy may look familiar to you! Homer is the most modern object in our exhibition. The figure was mass-produced to promote the 2007 The Simpsons Movie. Toys are constantly evolving, and makers and manufacturers are always looking for new designs and new materials. Lead toys, which were poisonous, were replaced by other metals and then by plastic. Some plastic toys have also proved to be toxic and harmful to the environment. What materials will be used in the future?

Toy Aeroplane

20th century, Tin and pewter

This toy is inspired by a World War II (1939-1945) aircraft. Toys often replicate real objects, and this plane would have been able to fly with a little bit of imagination, a child’s hand and some replica aeroplane noises! At the time, this might have been the must-have toy and would have been just as exciting as the release most toys have today.

Native American Figure

20th century, Lead

This is a toy Native American figure from the first half of the 20th century. Toys of Native Americans became popular in the 20th century following the rise of Western films and books that commonly had ‘Cowboys vs Indians’ battling for land and dominance in the western United States. Perhaps the child who played with this toy acted out fights from these movies, with matching lead cowboys. ‘Cowboys vs Indians’ has since become a symbol of racial stereotypes surviving from the colonial period in the United States. The toy’s inclusion in this exhibition aims to highlight how racial stereotypes have been entrenched into popular culture over the last century.

Toy Skirt

16th - 17th century, Lead

All that remains of this doll is her skirt! Perhaps it was damaged in the river, or perhaps it was thrown away when the child lost the rest of the doll. Many dolls during this period were made with scrap fabric and are therefore less likely to have survived. Today’s dolls have beautiful hair to brush, nappies to change and bottles for feeding. But how do you think children would have played with this doll at the time? Maybe she walked through the gardens, looked after other dolls, or perhaps she went on adventures with other toys.

Toy Horse

17th century, Lead

Gary’s research into this toy horse uncovered international links. A very similar example was found in Jamestown, Virginia in the United States. From the late 15th century onwards, many people embarked on the long journey from the United Kingdom to settle in America. Perhaps a local Durham family decided to relocate and took a similar treasured toy with them. Or maybe the design was created in the colonies and exported back to England.

Toy Knight

16th - 17th century, Lead

When this toy was made, knights were starting to be replaced by professional armies and soldiers. During the Medieval period, the idea of chivalrous knights developed, and kings and noblemen aspired to be gallant knights. This is an example of popular culture informing the creation of toys even in the 17th century.

Toy Soldier with Musical Instrument

19th century, Lead

Toy soldiers have a long history. Did you know the oldest toy soldiers were found in Ancient Egyptian tombs? Military strategists used miniature soldiers very similar to toys to plan out their next move. Napoleon Bonaparte, French Emperor and successful military leader, first popularised the use of miniature soldiers to organise his armies. Some toy soldiers were for playing. A child would march this toy into battle, or into celebration.

“Still wondering why someone would throw something in the river? Let’s ask A.C. Newton.”

People of Durham

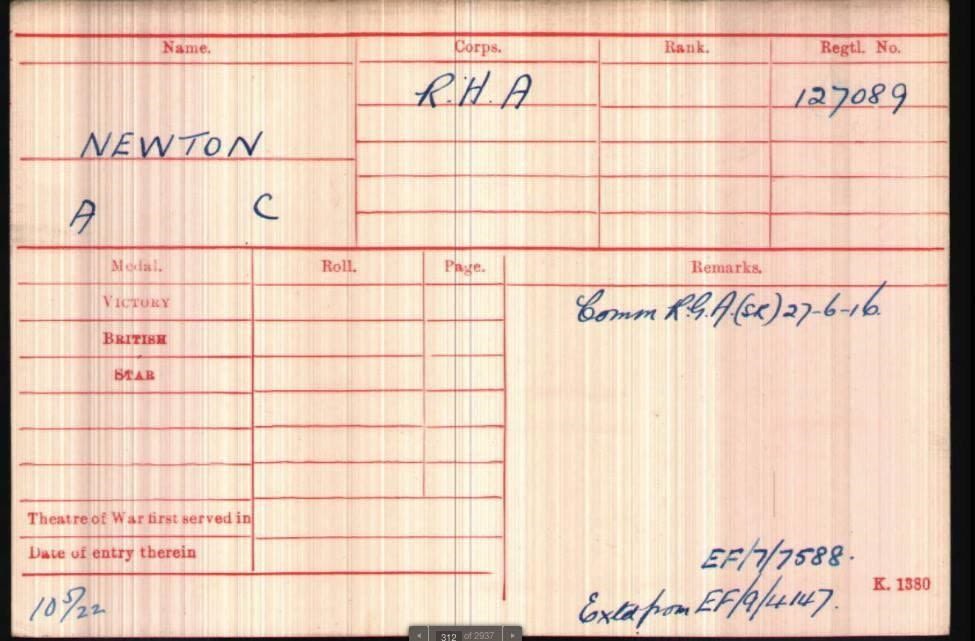

Alexander C. Newton: The War Hero of the River Wear

British War Medal c. 1918: Silver - Face designed by: Sir Bertram Mackennel. Back designed by: William McMillan

British Victory Medal c. 1919: Bronze - Designed by William McMillan

Gary found these two medals from World War I (1914-1918) near Prebends Bridge. They belonged to William Alexander (Alick) Cochrane Newton (1886–1954), who was Second Lieutenant in the Royal Garrison Artillery.

Gary researched A.C. Newton's life, discovering that Alick emigrated to Alberta, Canada. Later, he moved to Calgary and became one of the city’s most prominent businessmen and ranchers. He managed horses and cattle at the famous EP Ranch and became vice-president of Burns and Co (a big ranching company). Many of his family still live in Canada today.

Figure 1 - A.C. Newton medical card (photo provided by Gary Bankhead)

Some soldiers have been known to throw their medals into rivers or lakes after the wars they fought in had ended. Soldiers throw away their medals for a number of reasons: some as an act of defiance or protest, and others, particularly those who fought in World War I, because of the experience and the battles they fought in and the resentment at the way medals were handed out. There were very few medals for the war, and they were handed out regardless of battles they had fought, making them meaningless. We don’t know why Alick’s medals ended up at the bottom of the river – it still remains a mystery to this day.

Pilgrimage

For thousands of years, pilgrims have left their homes to make a journey to a place that is important to them. This may be a spiritual or religious place or a place to which they feel a connection. Durham was an important pilgrimage site in the Medieval period. In 995, the monks of Lindisfarne carrying St Cuthbert’s remains established a community in Durham.

Pilgrimages are still held to the shrine of St Cuthbert today. Some even follow the route taken by the Lindisfarne monks, from Lindisfarne, to Chester-Le-Street, and finally to Durham.

But what stories can the treasures from the river tell us about pilgrims and their journeys? Let’s find out!

Pilgrimage Ampullae

Souvenirs are an important part of most people’s travels, taking home a small piece of your journey to remember forever. Medieval pilgrims would purchase souvenirs at the sites of their pilgrimages. These are ampullae, and would have been used to carry holy liquids such as oil or water.

They were often decorated with letters, designs or images connected with a saint. They were a common purchase at pilgrimage sites.

Some pilgrims sprinkled the contents over farmland to ensure a good harvest or to cure sickness or failing crops. Others would throw these tokens into a river to offer thanks for their safe journey home.

The ampullae discovered in the River Wear would likely have been deposited by people from Durham, returning home safe after their pilgrimages.

Pilgrim Ampulla

13th-14th century, A lead ampulla with two handles and decorated with a crowned “W”.

The crowned “W” on this ampulla could be for Our Lady of Walsingham, a Christian shrine in Walsingham. This site used to be as popular for pilgrims as Canterbury was, known for its many miracles, leading to the name ‘England’s Nazareth’.

Thousands of pilgrims travelled to the shrine, and thousands still do today, connecting medieval people to modern times.

Pilgrim Badges

Pilgrim badges bearing designs connected with saints were another souvenir from long journeys. Souvenirs were thought to protect the wearers from harm, and even heal the sick.

Pilgrim badges were mass-produced using cheap metal and moulds, and cost around a penny for a dozen in the 15th century.

Hundreds have been found since in rivers across the UK. They may have been dropped by accident or thrown away as rubbish. They may have also been thrown in for religious or superstitious reasons – just as modern tourists throw coins into rivers, fountains, and wells for good luck today.

St. Cuthbert’s Cross Pilgrim badge

14th century Lead/tin St. Cuthbert’s Cross, possibly from Edward III’s reign.

This badge is decorated with St. Cuthbert’s Cross, which has become the symbol for County Durham. It has also been on the flag of the county since 2013. St. Cuthbert is the patron saint of Durham, protecting the city and its people from danger.

Thomas Becket Pilgrim badge

14th-16th century Pewter pilgrim badge depicting “Thomas Becket"

Thomas Becket, a saint who was venerated at Canterbury Cathedral, may be depicted on this badge.

A pilgrimage could take someone from their home to the next village, the other side of the country, or the other side of the world.

This badge could have been bought as a souvenir when visiting Canterbury Cathedral, meaning a journey of over 600 miles from Durham, to Canterbury, and back again!

Pilgrim’s Pendant

20th century Copper-alloy pilgrim’s pendant in the shape of St. Cuthbert’s Cross.

Pilgrim pendants were another souvenir from religious pilgrimages. This pendant also shows the popular image of St. Cuthbert’s cross.

The pendant would likely have been worn on Cuddy’s Corse, a pilgrimage from Chester-Le-Street to Durham Cathedral following the journey of St, Cuthbert’s body.

It may have been thrown in the river to bring good luck or kept to add to a collection. It is a much more modern souvenir, showing the popularity of pilgrimage throughout the ages.

Sacring Bell

18th century Copper – alloy sacring bell, discovered damaged.

A sacring bell, also known as an altar or sanctus bell, is a small hand-held bell rung during Mass in the Catholic Church. They were used to bring joyful noise to the ceremony and let those not in Mass know about the miracle taking place.

Sacring bells were removed from most churches after the ‘new Mass’ in 1969, although their use was not forbidden. This bell was found in the river slightly damaged, but hundreds may have had the opportunity to hear its wonderful sound in the churches of Durham.

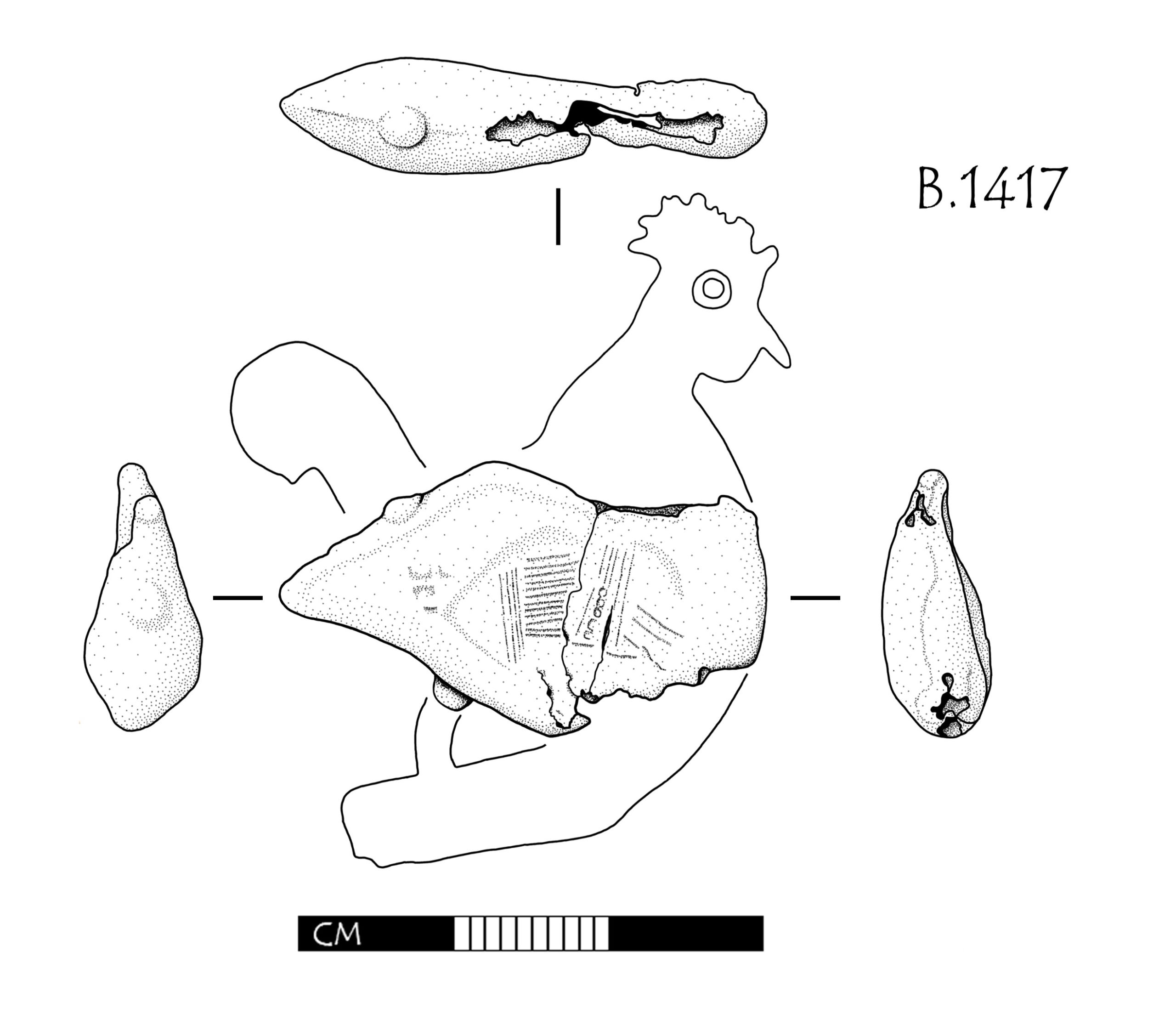

Pilgrim’s Whistle

13th -14th century Lead, hollow-cast Cockrel (whistle).

Pilgrimage could be a noisy occasion, with rattles, bells and whistles such as this one used to ward off evil and even lead bad weather away during the long journeys.

Illustration: Gary Bankhead

Illustration: Gary Bankhead

These whistles were often referred to as ‘Walsingham Whistles’, named after the flutes used in early Walsingham pilgrimages. Hopefully this whistle brought good luck to the pilgrim using it, but today’s pilgrims should definitely use plastic over a poisonous metal!

“People love to follow celebrity couples today, but did you know people did that in the past as well? Continue on to learn more.”

People of Durham

Brooch of Love: A Famous Couple?

17th – 19th century Copper-alloy brooch, possibly depicting Sir Walter Raleigh and Elizabeth I.

During the reign of Elizabeth I, there were many rumours that Sir Walter Raleigh was her lover. His courage and good looks made him a favourite of the Queen. Sir Walter saw his Queen's more unpleasant side once she discovered that he had secretly married her lady-in-waiting, Elizabeth Throckmorton. The newlywed couple were both imprisoned in the Tower of London soon after.

The original owner of the brooch may have admired the love story between ‘Lizzie and Walter’, or perhaps had their own forbidden or unrequited love.

Romance

Rivers have been associated with romance for centuries. Since the Medieval period, love tokens have been thrown into rivers in order to entice a potential love interest. As the Germanic superstition goes: “To win a maiden’s love, get a hair and a pin off her unperceived, twist the hair around the pin, and throw them backwards into a river.” It is unsurprising that the River Wear has become a treasure chest of romantic and sentimental objects. These objects represent the love, and sometimes, loss and heartbreak, experienced by the people of Durham.

‘Forget-me-not’ Mount

12th -16th century Copper-alloy mount decorated as a forget-me-not flower.

This mount is in the shape of a forget-me-not and would have been worn as a pendent or decorated a small casket.

Forget-me-not flowers were a symbol of love and remembrance in the Post-Medieval period. It is thought that this symbol originates from the story of a German knight and a lady walking along the shore of the Danube River. The lady stopped to admire the forget-me-nots growing at the water’s edge, but as the knight went to pick them, he fell into the river. As the knight was swept away, he tossed the flowers to the lady, imploring her to remember him.

A Forget-Me-Not flower

A Forget-Me-Not flower

Mizpah Token

20th century Love token made of lead.

This token is a type of Mizpah jewellery that is exchanged between partners or friends during a long period of separation.

Mizpah is a Hebrew word that means ‘Watchtower’ and is loosely interpreted as ‘May God Watch Over You’. The token is in the shape of a key and is decorated with two hearts. The right heart is inscribed with a passage from Genesis 31:49: The Lord Watch Between Thee and Me, and the left heart is inscribed with the word ‘MIZPAH’. These tokens would have often been worn or carried in the hope that a loved one would return.

Fede Finger Ring

16th – 17th century Gold ring decorated with a heart and inscribed in Latin.

In the Medieval period, courting couples would exchange rings to mark their betrothal. Such rings were called fede (faith) rings and were decorated with two clasped hands.

It is possible that this ring is a fede ring. The indents on the heart could represent the outline of fingers or clasped hands. The Latin inscription etched along the band is also indicative of a fede ring, as they were often inscribed with names, initials, or small messages. The ring is very worn, and the Latin inscription is difficult to translate due to its time in the river.

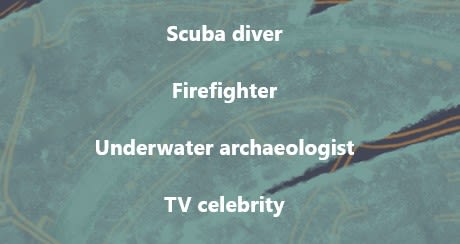

Engagement Ring

c. 1862 Gold 9k ring with a solitaire diamond.

In the Victorian period, diamond engagement rings were much smaller compared to modern rings. How such a beautiful ring was lost in the River Wear can only be speculated. However, the ring may not have been necessarily lost, but purposely thrown into the river. In the past, an unconventional tradition for divorced women or rejected fiancées was to toss their rings into a river or the sea in order to bring them closure.

Perhaps this was the fate of this engagement ring?

Finger Ring

c. 1998 Silver ring with a hidden message inscribed in the inside.

Posy rings, inscribed with messages or short phrases indicating love, promise, and fidelity, have been popular since the Medieval period.

The rings would act as a personal and constant reminder of the giver’s affection towards the recipient. The inside of this ring has been inscribed with the message "je t’adore EF y", which loosely translates to ‘I love you EF’ and the date c. 1998. This modern ring reflects a long-standing tradition of expressing love.

“Do you know what an Ironmonger is? Keep scrolling to learn about perhaps the only female Ironmonger in Durham!”

People of Durham

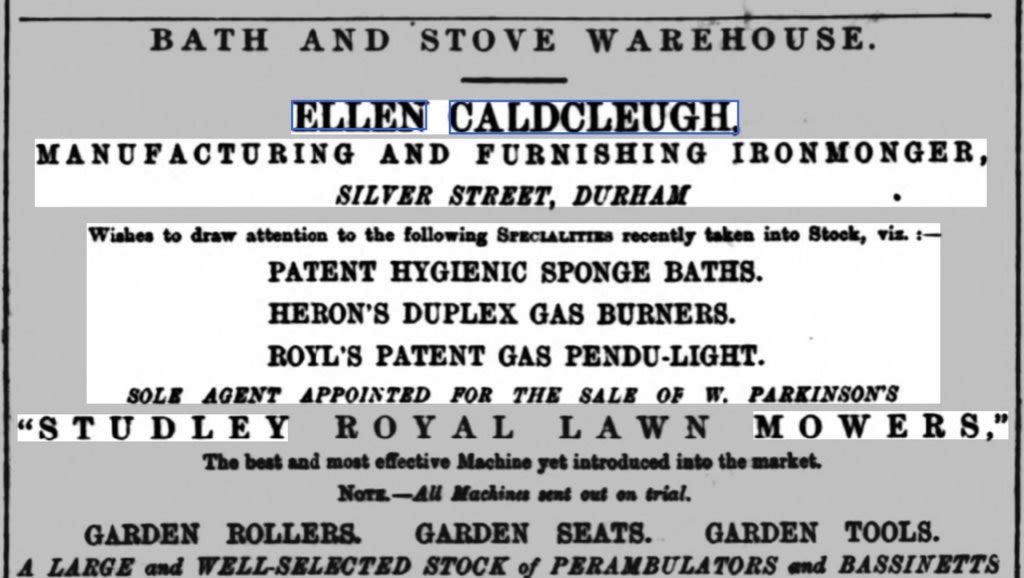

Ellen Caldcleugh: The Iron Monger Shop of Silver Street

19th century Nameplate bearing the inscription “Ellen Caldcleugh Iron Monger Silver Street Durham”.

Ellen Caldcleugh’s story is a fascinating one from Durham’s history. Her father ran a family iron monger's, a business which manufactured and sold iron goods. He died when she was 15, and the death of her mother ten years later meant that she became ‘head of the household’. By her mid-twenties, she took over the business and cared for herself and her seven younger siblings.

We have perceptions of educated Victorian women being employed as teachers, governesses or domestic servants, if they were lower class. Although we don’t know what Ellen’s role was, what would Victorian society have thought of a woman running an iron mongering business?

Whatever they thought, the business prospered under her leadership, and continued to be family-run into the 20th century.

Photograph of Ellen

Photograph of Ellen

Newspaper clipping advertising Ellen's shop

Newspaper clipping advertising Ellen's shop

This exhibition was created by the students of the MA Museum and Artefact Studies course at Durham University. Thank you all for visiting.

We would love to know if our exhibition has made you think any differently about the city of Durham and the world of underwater archaeology. Please fill out the Exhibition Survey in our Resources section!

How do you think some of these weird and wonderful objects ended up in the river?

How has this exhibition helped you understand the lives of Durham’s people in the past?

What is your favourite object from the exhibition?

Do you live somewhere close to a river? What could the river of your own city be hiding in its depths?

Get in touch on Instagram or Facebook at @archaeology.museum.durham, or even tweet us @dumuseums.

Visit the Museum of Archaeology from August 2021 at Palace Green Library to discover more of the remarkable archaeology that Durham has to offer!

Acknowledgements

The group would like to thank the following people:

Gary Bankhead, without whom this exhibition would not exist. Thank you for giving us the opportunity to work with this remarkable collection and providing constant help and support throughout the entire project.

Gemma Lewis and Mary Brooks for their guidance and unwavering encouragement, without which, we would have been lost.

Laura Littlefair, for her help and support with promoting the exhibition and photographing the objects.

David Wright for all of the assistance, guidance, and encouragement of our ideas throughout the design process.

Paddy Holland and John Roxborough for their help and support developing our teacher packs and family activities.

Fotini Kanellidou and Filip Titarenko for their support and assistance.

Special thanks to the Museum of Archaeology and Robin Brownlee-Sayers for photographing the objects and bringing them to life.

Jetton 16th Century Lead jetton, possibly part of a witch bottle.

Jetton 16th Century Lead jetton, possibly part of a witch bottle.

Pigeon Ring c. 1919 Copper-alloy pigeon ring with the inscription ‘WHS 19POO40’.

Pigeon Ring c. 1919 Copper-alloy pigeon ring with the inscription ‘WHS 19POO40’.

Anthropomorphic Lion 11th – 15th Century Brass candle holder in the shape of a lion.

Anthropomorphic Lion 11th – 15th Century Brass candle holder in the shape of a lion.

Georgian Intaglio Seal Matrix 18th Century Decorated with a gilt blue glass impression of a satyr engaging in coitus with a female nymph.

Georgian Intaglio Seal Matrix 18th Century Decorated with a gilt blue glass impression of a satyr engaging in coitus with a female nymph.

Dentures c. 1880s Upper dentures made from porcelain and vulcanite.

Dentures c. 1880s Upper dentures made from porcelain and vulcanite.

Ann Stuart Obituary Ring c. 1775 Gold ring, with rock crystal stone, covering a lock of red hair, on an ivory backing. The band reads “ANN STUART OBIT 1775 AGE 35”.

Ann Stuart Obituary Ring c. 1775 Gold ring, with rock crystal stone, covering a lock of red hair, on an ivory backing. The band reads “ANN STUART OBIT 1775 AGE 35”.

Pilgrimage Ampullae

Pilgrimage Ampullae

St Cuthbert’s Cross Pilgrim Badge 14th century Lead/tin St. Cuthbert’s Cross, possibly from Edward III’s reign.

St Cuthbert’s Cross Pilgrim Badge 14th century Lead/tin St. Cuthbert’s Cross, possibly from Edward III’s reign.

Pilgrim’s Pendant 20th century Copper-alloy pilgrim’s pendant in the shape of St Cuthbert’s Cross.

Pilgrim’s Pendant 20th century Copper-alloy pilgrim’s pendant in the shape of St Cuthbert’s Cross.

Sacring Bell 18th century Copper – alloy sacring bell, discovered damaged.

Sacring Bell 18th century Copper – alloy sacring bell, discovered damaged.

Brooch of Love: A Famous Couple? 17th – 19th century Copper-alloy brooch, possibly depicting Sir Walter Raleigh and Elizabeth I.

Brooch of Love: A Famous Couple? 17th – 19th century Copper-alloy brooch, possibly depicting Sir Walter Raleigh and Elizabeth I.

Pilgrim Ampulla 13th-14th century, A lead ampulla with two handles and decorated with a crowned “W”.

Pilgrim Ampulla 13th-14th century, A lead ampulla with two handles and decorated with a crowned “W”.

Thomas Becket Pilgrim badge 14th-16th century Pewter pilgrim badge inscribed with “Thomas Becket"

Thomas Becket Pilgrim badge 14th-16th century Pewter pilgrim badge inscribed with “Thomas Becket"

Homer Simpson Toy 21st century, Plastic

Homer Simpson Toy 21st century, Plastic

Toy Aeroplane 20th century, Tin and pewter

Toy Aeroplane 20th century, Tin and pewter

Native American Figure 20th century, Lead

Native American Figure 20th century, Lead

Toy Skirt 16th - 17th century, Lead

Toy Skirt 16th - 17th century, Lead

Toy Horse 17th century, Lead

Toy Horse 17th century, Lead

Toy Knight 16th - 17th century, Lead

Toy Knight 16th - 17th century, Lead

Toy Soldier with Musical Instrument 19th century, Lead

Toy Soldier with Musical Instrument 19th century, Lead

Alexander C. Newton: The War Hero of the River Wear British War Medal c. 1918 Silver, Victory Medal c. 1919 Bronze

Alexander C. Newton: The War Hero of the River Wear British War Medal c. 1918 Silver, Victory Medal c. 1919 Bronze

‘Forget-me-not’ Mount 12th -16th century Copper-alloy mount decorated with forget-me-not flowers.

‘Forget-me-not’ Mount 12th -16th century Copper-alloy mount decorated with forget-me-not flowers.

Mizpah Token 20th Century Mizpah love token made of lead.

Mizpah Token 20th Century Mizpah love token made of lead.

Finger ring, possibly a fede ring 16th/17th Century Gold ring decorated with a heart and inscribed with Latin text.

Finger ring, possibly a fede ring 16th/17th Century Gold ring decorated with a heart and inscribed with Latin text.

Engagement Ring c. 1862 The ring is made from 9k gold with a solitaire diamond. It is inscribed with the hallmark: 1123 375 N.

Engagement Ring c. 1862 The ring is made from 9k gold with a solitaire diamond. It is inscribed with the hallmark: 1123 375 N.

Finger Ring c. 1998 Silver ring with a hidden message inscribed in the inside of the band: JE T’ADORE EF Y.

Finger Ring c. 1998 Silver ring with a hidden message inscribed in the inside of the band: JE T’ADORE EF Y.

Ellen Caldcleugh: The Iron Monger of Silver Street 19th century Nameplate bearing the inscription “Ellen Caldcleugh Iron Monger Silver Street Durham”.

Ellen Caldcleugh: The Iron Monger of Silver Street 19th century Nameplate bearing the inscription “Ellen Caldcleugh Iron Monger Silver Street Durham”.